How Darwin Failed It And Dietrich Nailed It

Addiction centre worker, Andy Burford, writes about the realities of recovery, the hypocrisy of many judgements and why male friendships are important - for everyone. A must read.

By the age of fifty, most men tend to stay clear of social media sites that send their blood pressure rocketing for no reason, but when it comes to stories featuring those who are in the midst of active addiction, professional curiosity gets the better of me.

I should know better by now; five minutes into reading the proclamations of complete strangers and I’m biting down on that digital lip. Put simply, the internet is a corker for winding me up big time. Any feature on a local Heroin user appearing in Court in relation to a friend’s overdose, or an accidental death during a drug deal, will lead to the most stupid and cruel responses you can see online. Plus, I’ll guarantee you someone will have what I like to call their ‘Big Stupid Darwin Moment’.

Trust me on this one; scroll through the comments, and someone will pronounce:

‘It’s natural selection at its best with the druggies. Leave them to it and the evil scum eventually wipe themselves out’.

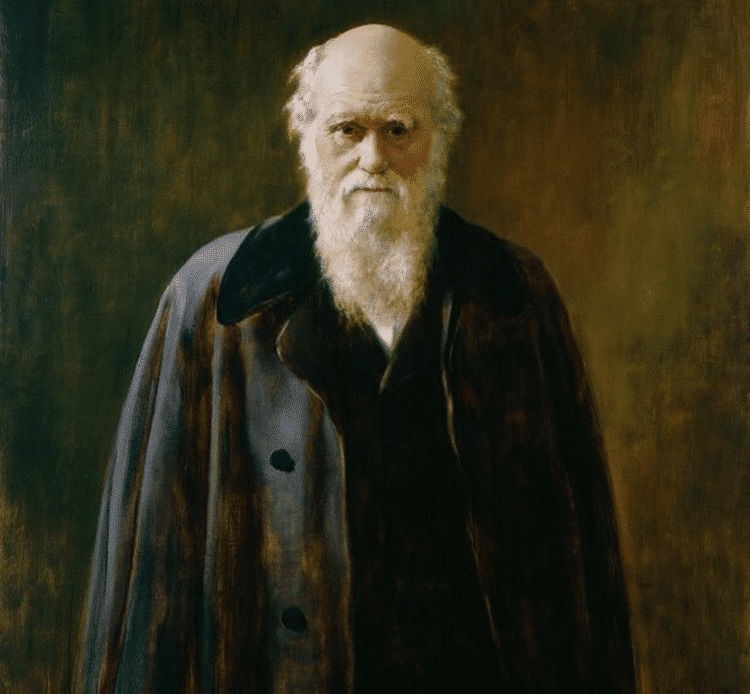

I know next to nothing about evolutionary biology, but I’m pretty sure that Darwin’s ‘On the Origin of Species’ failed to include chapters that relate to my clients when they recount dealing with historic abuse, surviving life in the Social Care System from the age of five, or regularly getting out of bed at 3am to turn off the lights when mum and dad have passed out in front of the TV.

As you can imagine, I struggle with the term ‘evil scum’ and the Big Stupid Darwin Moments. I struggle a great deal.

This is in no way a blanket excuse for the actions of those who have tainted the lives of you, or your loved ones, to satisfy a drug habit. I’ve sat in Court and heard heart wrenching accounts of how the innocent have suffered at the hands of the addicted. I could never justify the crimes that unfold before a jury, or claim that all our clients are somehow more sinned against than sinning.

What I can say, with absolute conviction, is that nobody is a winner in these cases. The truth, as Oscar Wilde stated, is rarely pure and never simple.

They events I’ve related above embody the memories of the men who sit opposite me at work; men who are seeking help to forge themselves some semblance of a new life from one which is careering off the rails. Some are here voluntarily, some through instruction from the Courts. Men whose use of Heroin, Crack Cocaine, Coke, Benzos, Alcohol and countless other substances have kept a carefully constructed veneer in place to stave off those early demons, only to have them replaced by a fresh set of horrors when the drink and drugs have begun to take their inevitable toll.

Between the tears and the awkward silences, their legs jigging with anxiety, I wait from them to talk. Motivational interviewing teaches you that the ideal ratio between client and counsellor should stand at 80/20. This is on a good day, and often comes after weeks of sessions where you try and build up their trust, replace the bravado and the blustering with honest talk about their drug use and its consequences, and reassure them that it’s safe to ‘let go’.

That nobody will laugh at them, and nobody will tell them to ‘get a grip’ or recoil with horror when they recount last weekend’s failed attempt to end their own life.

The media often reference Cannabis as a ‘gateway drug’ to full blown addiction to Class A’s; in the real world of recovery, we deal with gateway events. Trauma, poor mental and physical health, carers at the edge of despair, the unseen burdens of a life that became easier to bear with a glass in hand, a needle to enter the last available vein in the arm or groin, a pipe to share.

Very few of us go the entirety of our lives without an addiction hovering over us. If you use the definition of addiction as ‘not having control over doing, taking or using something to the point where it could be harmful to you’, then that’s one in three of the UK population. Just take a moment to properly process that. One in three.

Nice people take drugs. Nice people from nice, hardworking families. They hold down jobs and pay their taxes. Some other nice people who label the Heroin users as ‘scum’ will over indulge with food to the point of requiring surgery, some will stand anxiously outside the bookies waiting for it to open, and some will have scraped off the foil from ten scratch cards before they’ve left the door of the newsagents. We are, for all intents and purposes, a complicated and often hypocritical race of addicts.

It would be extremely foolish to envisage that fifteen or twenty years of daily Heroin use, with all its ensuing chaos and fallout, could vanish overnight. I remind myself that to have another human being confide to you the darkest chapters in their life is a privilege, and should never be taken lightly.

The day that someone finally rolls up a sleeve to show you the scars from years of self-harm, or discusses the degradations of sex-working when their body was the only thing left available on the shelf to sell, is something of a breakthrough.

However one area that has come to fascinate me – intrigue me, even – is the way that substance misuse affects male friendships.

Friendship between men has always been a tricky subject. We’re supposedly in the age of the enlightened thirty-forty-somethings, where most young guys grew up on a diet of Chandler and Joey sharing both an apartment and their innermost feelings, but even here the emotional content had to be tinged with humour to make it palatable. Most male friendships still revolve around discussing or participating in activities such as footie or the gym, whilst women’s close bonds – and their ability to encompass more emotional topics with apparent ease – can still leave some men squirming.

Added to this, we live in the age of silent networking. I despair at the site of commuters and schoolkids glued to their screens as if their lives depended on it, earbuds jammed in, every act designed to distance them as far as possible from the person next to them. So many ways to communicate with each other, and yet we’ll do anything to avoid having a conversation face to face.

Set aside the image of the boys ‘out on the town’ on a Friday night for a moment. We’re all familiar with that. Most of us have grown up with the comradery that the pub crawl enhances. We’ve seen the shirt tails let loose and the bonds of friendship deepen on the way home from the club, the ‘who can aim highest’ contests against the garden wall, and the arms around the shoulder that would never pass muster during the sober hours.

What strikes me is the amount of men I see who have no genuine male friendships left to speak of. More than that, they never seemed to have formed any in the first place.

For the guys I work with, it takes them aback when I ask them about it. It’s not a ‘set question’ on an assessment or a vital piece of info. These guys are used to talking about the women in their lives. The mother and elder sister who are worried sick and still lending them money or letting them sofa surf, the baby mother with whom they have supervised contact to see their daughter.

But other men? This is somehow dangerous ground. Here, they often clam up. If their father is around, he’s long proclaimed that he can’t understand how they reached this level of degradation. He loves him as a son, but can take it no longer. They last talked properly – I mean really sat down and talked together – when his son reached the grand age of thirteen.

His younger brother has become a ghost who disowns him. The school friends who joined him on the pub crawl and cinema trips in his teens have families of their own, and nobody wants an addict hanging around with their two year old.

So who’s left in the male magic circle? When I ask the guys I work with, the men they are now closest to are, unsurprisingly, other drug users. Part of the horrible wonder of the drug scene is your initiation into a whole new family bonded through financial desperation, crime, mutual dealers and – this is the kicker – those precious few minutes and hours when you’re high together. At that moment, the chances are you feel more in love with life and with each other than you’ve ever felt with your long departed partner.

Sounds bizarre? I’ve had plenty of people tell me that a good hit on Crystal Meth is better than sex, and they’re not joking. It’s incredibly addictive and almost impossible to conquer. Now picture sharing that feeling with someone else, regardless of gender, and you can see the attraction.

There’s an unspoken secret here that rarely gets discussed between heterosexual men who use drugs together; the shared euphoria they feel when ‘using’ in company that somehow morphs into the image of a close friendship akin to romance, when in reality they’re indulging in a particularly deadly ménage a trois with Heroin and Crack as their mutual love interest. The drugs are the only tenuous glue that holds them together.

As Recovery Workers, we see this all the time. Take away the drugs and your former friends in the scene fall away and dissolve into the shadows. The phone calls are ignored. Without that new dealer’s number, or your option of being the guy who’ll supply that final hit for the night, you’re dead to them.

So I try and work on cultivating new friendships. I believe they’re vital in men’s recovery, just as potent and as powerful a factor as getting back together with the estranged family or finally seeing the ex.

There’s something wonderful about hearing that one of my clients, clean for a few months, has spent the afternoon kicking a ball around in the park with a bloke he knew in Secondary School. That another is back in touch with the guy whom he once felt would be the brother he never had, and that they spent the afternoon on the beach with melted ice cream and the familiar comfortable silence between them rekindled.

Can it be such a coincidence that the men in Recovery Fellowships dispense with laddish ‘punches on the shoulder’ and greet each other with a long, heartfelt hug? I don’t think so. It’s good medicine, and it’s free. It’s a sure-fire way of saying ‘We’re both still here, and I’ve got your back’.

As for anybody who suggests its throwing shade on your heterosexuality, you’re more likely to be greeted with bafflement and a certain degree of pity. It’s always struck me as strange that we don’t bat an eyelid when men pile on top of each other on the sports pitch, but hug another guy in public? Whilst sober? Are you for real?

Well … yes … and no. I have to be a realist in my profession. Sporting a t-shirt proclaiming ‘Hugs not Drugs’ isn’t going to do much for someone with a deep vein thrombosis from groin injecting. But in terms of close male friendships, we could do far worse than bringing on the Bromances.

Science plays a part here too. I’m not a clinician or a pharmacologist, but studies over the last few years have shown that Oxytocin, a naturally occurring small peptide hormone, can help us cope with stress and anxiety and reduce blood pressure. It’s lost its sparkle somewhat since it was first nicknamed the ‘cuddle hormone’ and is no miracle cure (as it may also be associated with retaining traumatic memories) but helps promote bonding and possibly faithfulness to your chosen partner in life. Upping your hug quota for the day is a great way of boosting it.

As fathers and partners of those with sons, we’re getting much better at educating them on everything from the dangers of substance misuse to issues with pornography on the web, but when it comes to the value of caring for their own male peers we leave off dispensing any words of wisdom.

Instructing your boy on how to stand up to the school bully and ‘getting a punch in first’ might be all well and good for your own value system when they’re seven. It’s precious little help when they reach seventeen and are hiding the fact that they’re regularly being offered steroids, which they won’t turn down, for fear of being labelled ‘weak’. If you spent their formative years teaching them to be the strong and silent type who never sheds a tear, well … let me know how that one turns out.

If they’ve got a mate who’s worried about them, it’s the start of a support network. These friendships can deepen over time and last a lifetime, and they’re precious. Sometimes even lifesaving.

Maybe we could all learn a lesson from those who are in recovery. Those who’ve been to a metaphorical hell and back and now have a much deeper understanding of what really makes the world turn. For many of them, it started on the first morning in Rehab when their phones were taken off them, and they were forced – the horror! – to sit and simply talk to each other.

So get over yourself and give your mates a hug. Tell them you love them as often as possible. As morbid as it sounds, if tomorrow turns out to be the day that the aneurysm hits or you stumble under the bus, it’ll make things easier for them. Maybe not for you but hey, it’ll be a better last memory than that a ‘thumbs up’ on a picture of you in the local last Saturday night.

We need close male friendships, even more so when we’re fragile and emerging from a dark and destructive past. Marlene Dietrich nailed it with the oft quoted ‘the best friends are those you can call at 4am’.

Ask anyone who’s been around for more than three decades. They’ll tell you that we all need to make that call to a friend at some point in our lives, for whatever the reason.

When I sit down with my clients and we work on achievable goals, I can guarantee you there’ll be one suggestion in my top five; keep your best mate’s number on speed dial. One day it might, just might, be the phone call that saves somebody’s life.

Join our Community

Sign up for our daily newsletters for special offers, the best articles first, and chances to write for the site.

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.