Daniel Monks on new breakthroughs for disabled actors

Culture

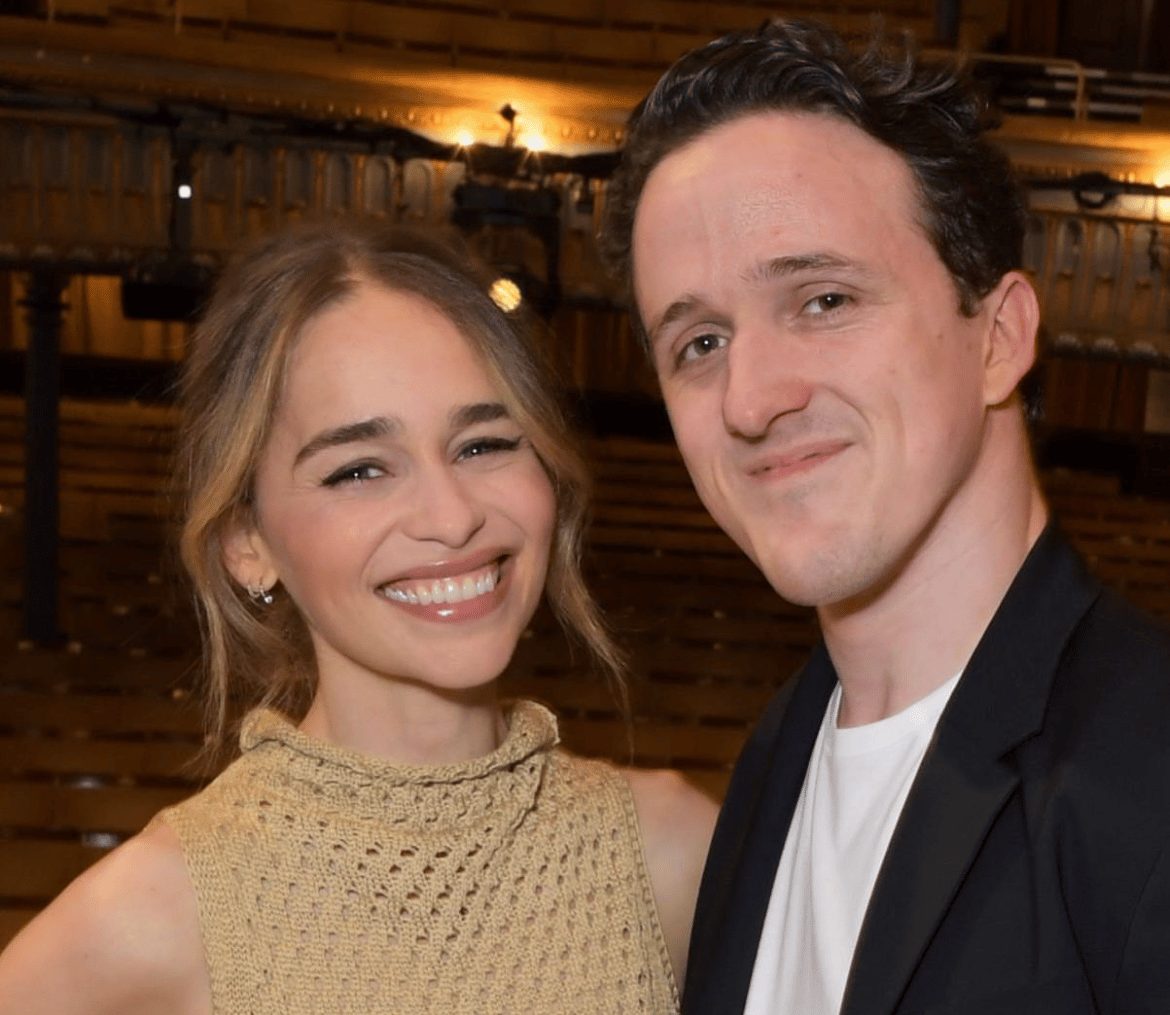

Daniel Monks is appearing in The Seagull opposite Emilia Clarke and in doing so is continuing to fight for representation for disabled people. We spoke to the supremely talented actor/writer/director...

Daniel Monks has been gathering rave reviews as the iconic Konstantin in Chekhov’s famous play The Seagull, opposite one Emilia Clarke and an equally impressive extended cast including the likes of Robert Glenister and Tom Rhys Harries. Directed by theatre genius Jamie Lloyd the production is a stripped back and innovative take on the classic, ultra naturalist and utterly electric. For Monks, it is the latest step in a burgeoning career which has seen the Australian jump between the stage (including The Real and Imagined History of The Elephant Man and Teenage Dick) and writing and directing his own films (the acclaimed drama Pulse). It also represents a further breakthrough in acceptance for disabled actors – who is hemiplegic after complications from a biopsy on his spine when he was 11 – an important point for this impassioned figure who knows the importance of representation for his community. As we discover, keeping focused on his mental health, with who he is and what he wants to do with your work, makes for a very inspiring man indeed.

Hi Daniel – take us back to how you first got involved, and what happened with the pandemic delay?

I had my London debut in Teenage Dick at the Donmar Warehouse, and after that, I was able to audition for The Seagull. I was cast in that at the beginning of 2020. Obviously because of the pandemic, we only ever got as far as previews and got shut down just after our fifth preview. Originally we thought we’re going to be off for maybe three weeks, which ended up being 805 days between us being shut down and starting again. So yeah, it’s quite a miracle that we’re back. And I’m so grateful to Jamie and Amelia for bringing us back on.

That’s a long gap, what else were you doing in that time?

I spent the first two months in London waiting for the show to go back on. And then when it was clear that wasn’t gonna happen, I went back to Australia to be with my family for what I thought was going to be three months. It ended up being 17 months. And then I came back in July last year to do The Normal Heart [at the National].

Did the production change in the interim?

Totally. Over that time, Jamie Lloyd, and Anya Reiss who has written this new version of Chekov’s play, made a lot of changes. They made cuts and reworked stuff, and for the absolute better – it was kind of a blessing because it meant that coming back into it, we all treated it like a new play, as opposed to just rehashing what we’ve done before. And also, after the two years, we were all different people and different actors, and Jamie was a different director and also the world that we’re presenting this play for is a different world than it was when we were first doing it. So it definitely evolved a lot and feels different to what we were doing in 2020, in a way that I think is much more relevant.

Can you tell us about the play and in what ways it was changed?

It’s a basically a Russian tragedy from the 1800s. It’s a play that’s often done, it’s one of the classics, and very well known. Anya Reiss is a brilliant playwright, she’s really updated and modernised it. Jamie had the vision to try to strip it back and look at it as if it was a new play, and not bring the baggage of the performance history. He also stripped back any artifice, to get the clearest distillation of the emotional truth, the emotional journey of the piece. So even though it’s technically a Russian tragedy from the 1800s, it feels hopefully much more modern and relevant and immediate.

How is that as an actor stepping into something so stripped back? Is it exposing?

Yeah, I mean, it’s basically just the whole cast on stage all the time. And the only thing that’s telling the story is the performances. It’s so weird, with this incredible sound because we’re all mic-ed up all the time. We can speak in very intimate voices that aren’t stereotypically theatrical. It does put a lot of pressure on us but there’s great autonomy with it as well. I feel like it really is a play where the performances are telling the story – it’s so execution dependent. There is a lot of pressure, but it’s also kind of thrilling.

Do you feel like you’ve got the space to make changes from night to night and expand the performance and grow it?

Absolutely. Jamie encourages us to really experiment with the performance style and the actual language of the piece. It is quite disciplined with clear boundaries, but within those there’s such room to discover it every night – and because my fellow cast members are so extraordinary, I think every night they’re so receptive and no one is like just rehashing a previous performance, everyone is like really alive to it.

How’s Emilia Clarke to work with?

Yeah, she is an absolute dream. I love her genuinely so deeply, she’s one of the kindest, most generous actors you can meet. It’s just really lovely as well, because she’s such a megastar, that she could have chosen a real vanity project, but she chose for her West End debut to do something with such artistic integrity, a very egoless decision on her part. That speaks to who she is as a person. I actually haven’t seen Game of Thrones, but I think that was kind of helped because it meant that I kind of met her with no preconceptions.

And tell us about Jamie as well, what’s he like to work with day to day?

He’s incredible. With him, I feel like I’ve grown so much as an actor. He has so much artistic integrity, and his trust of his actors is incredible. I don’t think I’ve ever worked with a director who really sees and listens to what you’re doing so incredibly well. I feel like this performance, at least from my experience of working with him, has been such a collaboration with him and a real exploration with him. I really feel like we really found that together, as opposed to me just finding that alone. Also his interest in theatre and the possibilities of what it can be, totally aligned with my tastes and what I’m interested in exploring experimentally. I just feel really aligned with him and I’m very grateful that I’ve had that experience. Hopefully, it will be the first of many times.

Can you just tell us how the audiences have been reacting?

It’s kind of amazing, some audiences almost respond to it as if it’s a comedy. And other ones respond to it as if it’s an incredibly heavy tragedy. It’s kind of both and that’s the brilliance of Chekhov, and Anya’s version. But what’s really exciting as well, which is so much of what we were kind of exploring with Jamie was really holding the tension in the place, and really having that feeling for not only performance, but also the audience’s sense of suspension and moving forward. As opposed to us just putting on a show and everyone sitting back and relaxing. It’s quite intentional that the show feels electric, even with certainty and understatement. The silence that you hear in this theatre in those tense moments is…well, I’ve never heard anything like it, it’s kind of amazing.

How do you prep and manage yourself for such a theatrical run?

I have physio twice a week for my disability and chronic pain. And then I basically I spend my days sleeping, resting or reading and then and then go to the play. I can’t really do social stuff and go out in the world, I need to keep my energy conserved. It can be a bit of a monastic lifestyle, but I find the work so rewarding and fulfilling that it doesn’t feel like that, it feels nourishing.

What about the emotional sort of weight of the story, how do you deal with that?

I mean, working or not I have weekly therapy, I think mental health is so important. Konstantin can be portrayed as, like a really tempestuous threat, or a tragic hero, but my reading, especially in this version of his play, is more in terms of someone struggling with mental and physical pain, and trying desperately to survive, and to connect.

I think, for me, almost the biggest kind of self care routine I have to do is not pre-show but after. Because if anyone knows how this story goes, it doesn’t end well for my character. Being able to take care of myself after that is important.

You made a splash with Pulse but how are you now looking at your career in terms of directing and acting?

I am writing but I kind of fell in love with theatre acting, funnily enough through screen acting and through filmmaking. I trained to Australia’s National Film School, and kind of fell into theatre unintentionally, and just fell in love with it. And that was where the opportunities were for me. But I’ve done quite a few plays over these past few years, and I definitely am interested in doing more screen work, not necessarily writing or producing as I have in the past but more screen acting.

Going back to mental health is there support within the industry? How do you cope with its demands?

It’s really hard. I’m such a believer in therapy, I find that incredibly helpful. And that’s why I don’t just do therapy when I’m working on an emotional character, sometimes it’s even more useful when there’s no work. My partner and a lot of my friends are in the industry, so they understand the challenges and there’s a shared camaraderie. But there’s also the added element of like, it’s hard enough being an actor in this industry, but then being an actor of any minority, there are just so many more barriers, and so much more rejections and it’s something that you have no power or control over. And that can feel especially disheartening. So I have a beautiful community of other disabled actors who often will just Zoom each other to rant about how hard it is and bond over that. I think community and loved ones and mental health support, are what gets me through it. I also think the pandemic has really shifted my priorities. Pre pandemic, I was living to work and now I feel like I have a much more balanced approach to my life. And I think my work is better for that as well.

What are the opportunities like and has it changed somewhat for actors with disabilities?

It’s interesting because I came from Australia and Australia is like a decade behind the UK. So when I first came to the UK, it felt like a utopia with all these opportunities for me. Australia is heading in the right direction, it’s just behind. The UK is further along but there’s still no real parity or equality when it comes to opportunity. It still has a long way to go, but I do think even in the past few years, it does feel like it’s getting hopefully better. I mean, like even this summer in the West End, there’s been me paying Konstantin in The Seagull, which is always an iconic role that’s not written for a disability, there’s been Lizzie Annis in The Glass Menagerie, a disabled actress, and then there’s also Arthur Hughes, who’s been playing his historic role of Richard III at the RSC and Barbican. It does feel pretty extraordinary that there’s three disabled leads in the West End this summer, which I don’t think would have happened a few years ago.

What do you hope that people will get from the play?

I think part of the reason why I want to watch this play is completely honestly, because the cast, who I get to work with, are so extraordinary and I would want to watch it because of the performances. Not only are these amazing actors, but it’s them doing their best work because of Jamie’s direction. I’m not necessarily putting myself in that…that’s too much pressure!

The Seagull is on at the Harold Pinter theatre until 10th September.

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.