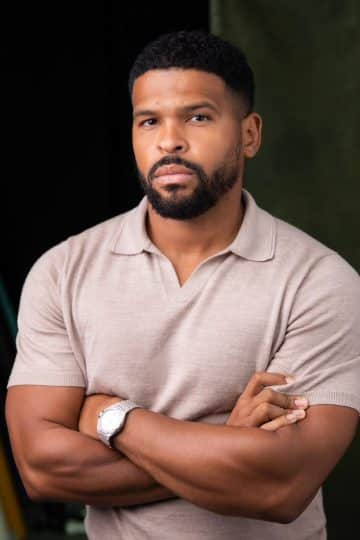

Harry Hadden-Paton on the exhausting joy of his West End run

Culture

Downton Abbey star Harry Hadden-Paton talks to us about his Tony-nominated role in My Fair Lady, now in the West End, the physical strain of musical theatre and his lesser known boy band, Spunk...

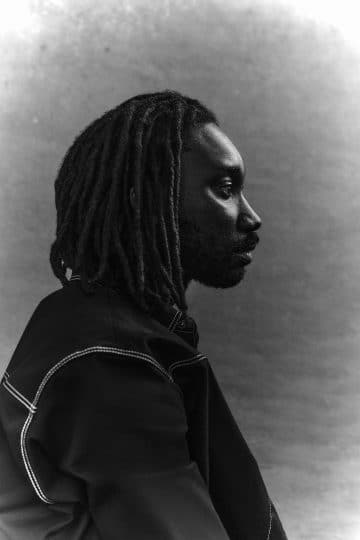

Harry Hadden-Paton is right in the thick of it. The ‘it’ being a run of West End musicals, with him starring as Henry Higgins in the acclaimed revival of ‘My Fair Lady’. It’s his second time in the part, having been Tony-nominated in the initial hit revival of the show on Broadway, but this one in particular appears to be a demanding one. Laymen like us may vaguely imagine it’s fairly demanding to perform in such shows but the way Harry tells it, it’s like training for the World’s Strongest Man Contest each day, only without all the chicken breasts. That’s a terrible comparison, and indeed Harry, much beloved to all of us Downton Abbey and The Crown fans, is keen to stress the joy and fulfilment that is the reward for the exhaustion. And the fact that this ‘My Fair Lady’, with Amara Okereke starring opposite Harry as the first black Eliza Doolittle, is one which truly hits home at a moment when representation and matters of class have never been so important. Here’s our in-depth interview with Harry, a very lovely man clearly working at the top of his game (with assistance from some scary-sounding sinus tech):

Hi Harry, how’s things? Are you doing all right?

I’m tired, it’s a bit of a slog doing this show particularly, but it’s great. It’s also kind of lonely because my base is in Dorset now, with my family and three girls. I’m up in London during the show and then back and forth, which is good on the one hand because I get to rest, but I feel like I’m not living as quite as a heightened state as I should be because you need to prepare for these shows.

Can you give us an idea of what it’s like? The demands and the sheer workload?

Well, this is it. I’ve got two shows today. The key, and I’ve got my New York dresser in my mind, who’s nickname was the Mayor of Broadway, he’d be like, “Just take one show at a time here. One show at a time.” And that’s it. The big difficulty in this one is we’ve got about we’ve got about an hour before we’re getting ready for the next show. That includes getting out of costume and makeup and wigs, eating, sleeping. And then getting doing it again. So that’s a quick turnaround.

Doing a musical is all new to me. I was attracted to it because it’s more of a play, really, than a musical; it has some songs. But the maintenance is such a big part of it. I had no idea. I’m having physical therapy twice a week. And I’ve got all sorts of contraptions, I’ve got steamers, I’ve got the Theragun, I’ve got something called a navage that you have to get from America, where you put things up your nose – it fires saline in one nostril and pulls it out of the other, and holds it in a little bowl. It’s disgusting. But dust or an an allergy, can make a real difference to a show.

It’s to protect your voice?

Yes, it’s for my voice by clearing my sinuses, it’s all linked together.

There’s also a muscular thing to deal with. My character goes through quite a transformation. He gets caught up on a journey that involves a breakdown almost, and he carries a lot of it in his neck and shoulders. We see him go from a sort of erect gentleman to a kind of ‘what am I?’ Doing that eight times a week puts a lot of pressure on the muscles.

It’s crazy, but I have to go up and down a spiral staircase 32 times a show. Which of course in the rehearsal room, I thought, ‘this is great, I’m making him young and athletic and energetic.’ What I wasn’t thinking about was doing it eight times a week. So I have to stretch and pound my quads and my thighs and make sure that my knees are alright. It’s so boring, but there’s so much that goes into just getting out on stage. And obviously, it takes a village. There’s lots of other people helping me. The main thing is, when you’re on stage, it’s great. You don’t think about all these things, but it’s the moments when you’ve got a big scene coming up, and you have to ramp yourself up for it again. That’s where Laurence Olivier said the key is to being a good actor. That all you need is ‘concentration and stamina’. And never have I felt that so much.

It sounds like training for an Olympic sport.

It does feel like it. I’m learning a lot. This is the first time I’ve used a microphone on stage as well. I’d rather not and technically, I have the facility to fill that space. But when you’ve got a 30-piece orchestra creating a wall of sound in front of you, you have to have a microphone to make sure that the sound is balanced.

I’m sure there’s a way in which I could whisper my way through it, and save myself a lot of trouble. But then the audience aren’t getting the physical breath, which is where you capture people’s emotions and feelings and other things that aren’t tangible. You can get a laugh by just making sure they can hear the line, but they’re not going to be breathing with you unless you’re projecting and throwing energy at them. Maybe I’m wrong, but that’s how I feel. And it’s ultimately satisfying. I love putting myself through it, at the end of the day.

When you get the applause at the end, I imagine it’s all worth it.

You get that and you get the sense of it being such a wonderful piece. It’s ‘Pygmalion’, an extraordinary play with both of these characters who go on incredible journeys where they change but don’t really change, you know? Eliza becomes a princess but that’s not what makes her special. It’s the fire inside her that was always there. It’s fascinating, the themes of class and the ability to transform and in this production, race, which is so relevant to today. It asks a lot of questions and it feels important to be doing it again.

Did you go back and sort of watch the film in preparation?

When we were in America, I did. I didn’t really want to, I wanted to make sure it was my own, and then throughout the run, little bits would pop up. Our director was most keen on the play, starring Leslie Howard and Wendy Hillier. When you do something on this scale, the director was saying it’s a big deal, wit the estates of [songwriters] Lerner and Loewe to keep happy, and the estates of Bernard Shaw. But what comes with that is we have access to the play and to the film of ‘My Fair Lady’, the film of Pygmalion that Bernard Shaw wrote – and we can cherry pick sections or bits of dialogue, change them, and use the different versions that he wrote to make it more relevant to now. So we’ve managed to calibrate it to make it more relevant to today. And that’s exciting. That’s the point of doing a revival, I suppose, that you can go back to the old texts to see what they’ve learned, what they haven’t learned, how society has moved on, or how it hasn’t moved on. The key is to shine a mirror on society today. And you ask the audience those questions.

So I knew it wasn’t going to be like Rex Harrison’s performance. Today, if I did it that way, I would be booed off stage, I think. The interesting thing, with it being kind of Eliza’s story is that Henry Higgins has the final number. He has, and this is another term I’ve learned, ‘the 11 O’clock Number’. The audience have to empathise with him. They don’t have to agree with him or like him, but they have to be with him. They can’t dismiss Higgins immediately, being sort of a misogynist and bullying. So it’s been really interesting finding a way of playing him for today.

I’m giving myself away to empathise with his choices, right? I don’t necessarily like him. He is a flawed man, let me be clear. But there’s maybe a world in which, if we were around today, we would be able to label him as maybe on the spectrum or having difficulty with social cues. Like Sherlock, like Doctor Who, like any of these genius character archetypes that we’ve had in the past. There’s a method to his madness that isn’t okay, but having to perform it, I understand it. It means you can do a lot of the terrible things he’s saying, as unconscious. It doesn’t take away from the humour, interestingly. Which is a kind of fine balance. At the end of the day, it’s about two people who are desperately trying to communicate and trying to be on the same level, but they keep missing each other. And what keeps it going for three hours is the frustration of them not necessarily getting together, but getting along. He keeps saying the wrong thing.

Was it important to you to treat his breakdown in a sort of contemporary way with regards to mental health? And is that hard to deal with?

Yeah, I’m putting my heart out on the stage every night in a way that is equally exhausting, but the key is not to sit in the emotion of it. Maintain the intellect and the effort of understanding. The passion and that desperate search for, ‘what is what am I feeling? What am I doing? Why am I feeling like this? Why is she gone?’ And what if, as the character, I can keep it active, and not sit back and lull into a woe is me – then we stay with the characters till the end. That comes out in a different way every night. It’s not always a breakdown. It depends what I’m getting from Eliza and vice versa. And the audience, where their concentration is. That’s what the joy of doing live theatre is, I’m reacting to the audience – it’s sort of a three way thing. If they’re distracted, if someone’s phone’s going off, I’ve got to motor this beast forward, so that I’m at the head of them, and they’re not thinking about the phone, and they’re having to keep up. Whereas if they’re listening, I can sense when they’re breathing with me. And then it’s as simple as if I hold my breath, I can feel the whole audience do that too, if I leave something in the air. And then I can take it on to the next bit. That’s the joy. It’s why I’m still doing it. That’s why I put myself through it. Because I don’t think there are many roles like this that you get to do in life. I’m really lucky to have it.

And that’s what we’ve missed about the theatre over the last couple of years, when you’re all sharing in the moment of it.

The only shows I’ve ever walked out of are shows that have been running for too long. The actors are anticipating laughs or waiting for laughs. I’m so conscious of that, and I’m pretty proud of what we’re achieving in the moment and that it still feels fresh. I’m a stamina workhorse, I’m an Aries, so I will butt my head against that wall, and drag the show through it. Trying to keep ahead of the audience so that they’re guessing and not anticipating, and not telling them when to laugh. Treating them as intellectuals, as clever, because it’s a long show. If you start waiting for laughs at the beginning then you’re screwed, because they’ll be asleep by the end. Getting to a place where you’ve got an audience breathing together in one room feels extremely special after all we’ve been through.

In New York, I went back and finished a show that was cut short, because of COVID. It was very moving in one respect, because we’d all been through this thing together, and we had been meeting up like this over Zoom over the year. But the audience was still wearing masks. And it makes it makes such a difference now not having masks. You hear the laughter, you can finally take people out of their problems and whatever they brought in, and share that air. I think it’s been really missed. That’s what I hear every day: Thank God we’re back in the theatre. It’s weird. It touches people on an elemental level.

How do you suss out an audience? Is it something that you kind of like consciously look for when you first out there? Or is it just something that you feel as you’re going through?

It’s in the moment. A new theatre means I’m still negotiating and working out what works best. We’re quite far from the audience at the Coliseum, which is good because everyone gets a great view, but it also means that the reactions aren’t as quick as you think. It’s not instantaneous.

But I know if they’re laughing too much at the beginning, then I’ve got to shut them up a bit! Because they will run out of steam by the end. That only comes with doing a show over and over again. My way of doing it is like, ‘right, are you coming with me? Let’s go. You got to pay attention and listen up, because we’re off. We’ll enjoy ourselves in a bit, but you need to stick with me because this is long.’

You can really feel what’s called ‘the click’, another musical theatre time I’ve learned in the last few weeks, you can really feel when they go, ‘Okay, I’m in it.’ And they’ve stopped thinking about where they’ve been or what they’ve been doing and they’re in it. You can feel it and it tends to be in the study, when Eliza turns up. We go, ‘Right, this is the story I’m making you into it a Duchess,’ and from then it becomes a joyful game of getting the ball out to the audience and seeing what’s there. And if there’s nothing there, it’s hurrying up to the next bit. It’s so mellifluous – that’s the joy of it. I wouldn’t do this to an empty room every night.

How are you enjoying the actual singing itself? It’s something you’ve you’ve always done?

I love singing. It was my first passion. I was a choir boy. Then I had various bands. I had a mock piss-take boy band called Spunk at school. We did a gig at the Hammersmith Palais, hosted by Darius Dinesh. That was the highlight of Spunk.

I was a sportsman at school and I did Hamlet, so I was a bit of an all rounder really. But singing was always something I love. It’s medium that works on an ethereal level that touches the soul rather than the intellect. And then I made a sensible decision. When I was 21, I went, ‘life’s too short. I’m going to do what I love. And what I love is acting and singing. I think there’s a longer trajectory of a career in acting, so I’m gonna go with that.’

Somewhere along the line, I did an audition for a musical for Jamie Lloyd, who’s a theatre director I work with a bit – he got me in for a musical workshop where a casting director heard me, and he got me into a couple of workshops for different projects. And then this came along.

Fortunately, the precedent of singing on this show is not really there. Rex was not a singer, certainly not. He does the speaking-singing bit. I did go into it. I had singing lessons before we did the job. I learned the melodies for every single song, and had that at the beginning of the rehearsal process. But our musical director started pulling me away from that, saying it looks a bit boring. It was written with Rex in mind, so it does work better doing what he did. What that does is give me a lot of freedom. It’s not the same every night. If I’m in the moment, and I’m thinking of the sense of the lines, then whether I’m singing or speaking, it will change each night with regards to where my voice is sitting, what I’m getting back, all sorts of aspects. I hope when I do sing, it sounds good, and I do love it, but I mean, how Amara who plays Eliza sings to the level she sings every night, I just simply don’t know. I don’t have the knowledge. She’s teaching me warm downs. I think I wasn’t warming down enough previously and it’s like any muscle. Apparently if you blow through a straw that helps. I have no idea. All I know is that she is able to sound incredible every night. My voice will be tired tonight and I’ll have shows where I go, ‘wow, that wasn’t crystal clear.’ But it doesn’t matter, because no one’s expecting me to sing beautifully.

How is your relationship with her and how does that also develop as the run continues?

Acting is weird, because you’re thrown in with these people, you have to be quite intimate very quickly. She’s so brilliant, and she came in prepared. She’d learnt it all. Great attitude. She worked seriously hard. What was lovely with our director was that he put in some markers, and very much said to us, ‘you stick to these markers’, but within that you need to deepen it. ‘Deepen it, not broaden it’. So within it we are listening, we’re in the room and it’s slightly different every night. Sometimes I’ll need more from her, and sometimes she’ll need more from me and you don’t even talk about it. We know, because we’re telling the story together. She’s remarkable.

Do you get to socialise at all?

I can’t do it. I have to rest, I go to bed, and I know she does the same. We’ve got voices to look after and our bodies. This is a tricky setup. Because we do two on a Thursday, one on a Friday and two on a Saturday. So we’ve got five shows in three days, and that is particularly hard.

When dealing with Henry and dealing did you want to look at him through a lens of changing masculinity?

Yeah, of course. Firstly, I didn’t think I was gonna get the job. I didn’t want to audition for it, because I knew it was going to go to an older statesman type actor, which is what it always previously has been. My agent convinced me and said, ‘No, I think this director wants to go somewhere a bit different with it.’ And of course, he did. Because #MeToo had just happened. Both my previous Elizas were older than me, in fact – we wanted to create her much more as an equal. And if you go back to Shaw, that’s what his intentions were. It was Rex Harrison, really, that wanted to be the lead and the puppeteer, and all that imagery of changing the woman, which is about antiquated male control. Whereas if you read the text, it’s her that has the agency. She’s the one in Covent Garden that hears what he’s saying, and takes the little money she has and turns up at his house in the posh part of town, and says, ‘I need to better myself, can you do it? I’ve got money to pay you.’ Which is somehow glossed over previously. Isn’t that wonderful? Now society has changed, and that’s why we can look at these texts, and why Shaw was such a genius. That’s what makes this production different, she’s in every way an equal. She’s turned up of her own accord to say, change me, I want some of this. And she works hard. He’s not bullying her into it, she’s trying her hardest to do it. And the tragedy is, and this is the argument, I guess, is that it leaves her with nowhere to go. Because she’s never fully accepted in either [class]. That’s more to do with the class issue we have in this country, which isn’t a thing in America. This is something they’re picking up on more here.

So it’s more about tweaking the whole show rather than just Henry. As I said earlier, I think giving him a kind of a problem about understanding social cues and behaviour and if you like, naivety. That helps in one way. But there’s many other things going on, it’s her strength and her determination that make it much more relevant to the day. And since we did it in America, Black Lives Matter hit, which again, asks other questions. Now we have the first black Eliza, which is wonderful. I’m so proud to be part of something that’s representing in that way. In showing girls like Amaro can do anything.

Thanks, best of luck with the with the run and get some rest.

I’m gonna go and steam. I won’t ask you to see that, and not the sinus one up the nose either.

My Fair Lady is currently showing at the Coliseum in the West End.

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.