Brothers – the short film about mental health that has everyone talking

Culture

'Brothers' is a quite astonishing piece of art; a raw and real depiction of mental health. And no wonder: here's the story behind it by director Huse Monfaradi and actor Michael Workeye, who's own life informed the drama.

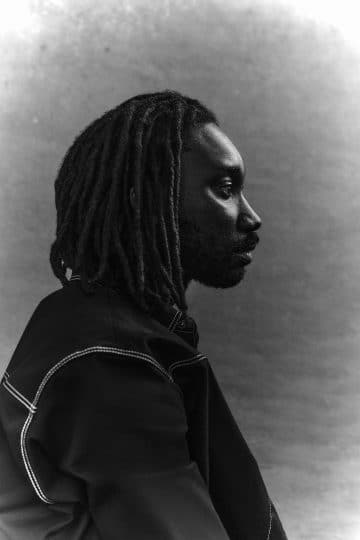

Since it’s release last weekend, ‘Brothers’ – a 14 minute film written and directed by (and as we’ll find out art directed, and catered by too) Huse Monfaradi, and starring Michael Workeye and Jay Lycurgo – has gained plaudits and praise from everyone from June Sarpong to David Schwimmer. An incredibly raw and emotional look at two friends dealing with the mental health problems of one of them, Huse was inspired to make it by the real-life story of Michael and his older brother. The final film is a semi-improvised drama filmed in the flat where the two actors lived together, and is truly something special.

STUDIOCANAL UK and suicide prevention charity CALM came on board to support the film, which you can watch here for free: www.brothersthefilm.com

We caught up with Michael and Huse over Zoom to find out more…

Where did it come from and how was the gathering of the production as a whole?

Huse: This is quite a lovely story. I’ve known Michael for some time, because he worked in my friend’s restaurant since he was very young.

Michael: Which is where I am right now!

Huse: Tough times for an actor, tough times…so I kept an eye on Michael’s career and I saw he went to drama school. But it wasn’t until a few years ago that I took a more active interest in his career and started to go to productions he was in at drama college. It was around that time that my girlfriend said to me, ‘you need to do something with Michael because he’s on the up and a very charismatic young actor.’ I was looking to do some drama rather than commercials and music videos, which is what I’m doing at the moment. I took him out for a coffee and said I’d really like to do something with you, but I don’t know what – tell me about yourself and your life story. I’d known him for some time but at a superficial level, I didn’t know much about his family background.

In that conversation he told me about his brother and his brother’s mental health struggles. And it was super captivating, the way Michael spoke about it with such clarity and such an adult head on his shoulders to deal with it…I was really touched and impressed by it. It moved me. He told me he was having a house party that weekend, and I said to him, ‘would you mind filming some of that on your iPhone?’ Because that could spark further thoughts in my head. He sent me back this iPhone footage, and that was where I saw Jay properly for the first time, who plays the character of Jase. And I literally had a lightbulb moment and thought why don’t’ we take Michael’s story about the relationship with his older brother, who’s been in and out of mental health institutes, and take that story and make it about two best friends and call the film ‘Brothers’, as an analogy.

I was very hesitant to say anything to Michael because I wasn’t sure how he’d feel about basing a film around something so personal to him and his family. But he said yes right away, because like me he felt it was a subject that needed some attention and awareness drawn towards it.

That’s how it happened but you have to understand we didn’t have any money at all. We had no production help, it was friends helping out. We shot it in Michael and Jay’s student house; from Michael saying yes to us filming it was a very short period of time, because they were leaving their student house. It was really guerrilla film-making in its purest essence. There was no script, we just had two pages of bullet points, and the boys riffed around that. It was an unusual way of working, semi-improvised. I didn’t want to restrain them by words on a page, I wanted them to explore the subject matter and the characters without a film-maker like me telling them what to say.

And it worked! Sometimes you have to adapt to the situation and roll with the punches. And it all worked really well.

it wasn’t until we finished it that CALM and Studio Canal came on board thanks to our Exec Producer Mark Whelan, who was brilliant in putting it in front of them and bringing it all to the screen.

Michael, how was it being in the midst of that process of touching upon personal issues and how did that manifest itself in your acting?

I was very caught up in everything as it was then: my brother was still in hospital at the time so I didn’t have permission from him to make the film in the first place. That was the first border mentally to cross – will he be alright with this when he comes out. On a whim I decided to do it, not knowing what his reaction would be. Thankfully now, he’s ok with it, but at the time we didn’t know, so we all treated it with so much respect.

Although it was done over a short period of time there was patience applied, time was taken out of Jay’s time and my time to really discuss the issues that [my brother] Daniel was struggling with. To help clarify what the exact issues were between me and him, and that dynamic at the time.

In terms of how we shot it, Huse introduced us to the Shane Meadows style of working where you’re given a conflict or given a style and you basically just play it to its utmost truth. It’s just about connecting. I had a brilliant chemistry with Jay already just from working together in drama school but up until that point we’d only ever been presented with text based work whether than be plays or auditions that we’d done. Now we were presented with an idea basically – which we could improvise around. Luckily because we already had that bond and were best mates and lived together for two years, it was really easy. It shouldn’t have been easy but it was.

In terms of a process, it was my favourite acting style, where it was about, ‘don’t’ worry about it we’ll get it right.’ And also having the permission to go as far as you want. [Huse said] I’ll reign you back in if it’s not truthful or I’ll tell you to go further if its something that will bring out more truth in a scene.’ It was great for developing as an actor as well as getting this story out of my head and into some physical manifestation of my actual life.

Were there any things you wanted to specifically bring into the film, in the depiction of mental health, either that you picked up in research or from personal experience?

Michael: It was the aspect of having fun but that leading to – and we didn’t explicitly say this – a marijuana psychosis. You have a lot of fun in your teens, you experiment with drugs, everyone is having a nice time until eventually you are presented with someone who has poor mental health. It’s the inexperience of that that was at the forefront of what we were trying to capture. What do you do in a circumstance where you’re presented with someone who’s your brother or best friend who is suddenly showing signs that they are not themselves.

Even going back to our first conversation over coffee – just the fact I was able to articulate myself over what was going on was just an indication that making the film with Huse was the right thing to do. That’s all we had to go off. We just had us but it made it very easy. We knew the premise, which was your first interaction with mental health. We knew what the relationship was between me and Jase. And that’s it.

Huse: We also talked a lot about not wanting to do anything that was extremely specific in the storyline. Ultimately it was a work of drama it wasn’t a documentary. We never pushed it too far going into details and facts and figures, because we felt it needed to be a bit broader so it appealed to a broader audience. We’re very clear we’re not authorities on mental health but we wanted to tell this story that was clearly about someone struggling with their mental health. You have to tread a very fine line because you don’t want to come across like you’re preaching and you don’t want to come across as if you have the answers.

The only thing we had binding this all together was Michael’s real-life experiences with his brother. And that counted for everything.

Was there a desire to capture the awkwardness and difficulty in dealing with these issues, particularly when it comes to men?

Huse: Well I think in the most simple way to answer that is we decided to call the film ‘Brothers’. They’re best friends, they’re not brothers. But there’s still a lot of physical affection there as well as an emotional connection between them. They’re not family members but they’re as good as family members.

We never explicitly say it, but its in every scene that they share and are emotionally open. Maybe not always, obviously, but certainly for the story that we told it was very important.

Michael, was it about capturing important moments for people, expressing a bond or a time when a relationship moves to a different level – was that an angle for you?

I guess so, it’s how you have gone from being one thing – in terms of how society views you – and then suddenly one person is presented with an illness, and the other person carries on going with life. And it’s the guilt of that person who has proceeded with no stigma attached to them – who can still smoke weed, can still have parties, can still work – but the other is being forced into being under this label of being unwell.

That 100% will impact on your relationship, whether it’s a friend or a brother, and its one of the hardest things to deal with. It’s the lack of acceptance from that person who’s not well and you trying to mask how you view them because your view will ultimately change. I guess it’s about exploring that transformation in their relationship.

It’s easy now with my brother because after 8 years he’s finally come to term with the fact that he has a mental health illness and it is a recurring one and he can have remissions and it can all be ignited again. But that awareness is never there at the start. If it is then you’ve got someone who can show incredible amounts of awareness about how they’re feeling, but usually it’s so difficult to come to terms with having an illness and that goes for everybody involved.

And in the film you’re not giving advice on how to deal with it, just presenting it…

Michael: I don’t think in the film we try to say the way my character deals with it is the right way to deal with it, but more or less trying to show the train of thought people go through. ‘Maybe I’l leave it to the experts or maybe I won’t be there because I’m going to provoke you if I’m there – and I’m going to make you feel you’re not getting on with your life.’ Or ‘maybe I will be there and I’ll be there for you and help you come to terms with it.’ There’s no right or wrong when you have never dealt with it before. I think that was ore the angle rather than saying this is what you should do when you encounter someone with poor mental health. It was more about how the hell do you navigate someone just coming to your house after being away for a few months in a mental health [institution] who you haven’t seen.

Huse: When we were coming up with ideas about where the storyline could go and what the characters could do, we didn’t want to provide a solution. We didn’t want to provide a narrative that was very specific and had to be fact checked because I think youre treading on dangerous territory there – I don’t want to come across as we know best, because we don’t. I’m a director working with two brilliant actors and it just so happens that the story is based on one of their true life experiences dealing with mental health.

But there is more discussion around mental health at the moment – did that help with any aspect, even the confidence that the production would find an audience?

Huse: When you do anything around subjects such as mental health or race or gender, you have to do it justice, you have to be careful. When you’re doing it you’re not thinking you’ll get attention. We certainly did it, or I did it, because I wanted to make a powerful piece of drama, and also I wanted to do Michael’s story justice.

And because we went about it on our own without any support we didn’t think about things like that. It wasn’t till after that we did, when we had this finished film where so many brilliant people had invested their time and effort into it, for nothing. Everyone from the DOP to Ed Harcourt who wrote a fantastic original score for it – everyone said yes straight away because they believed in us and the subject.

When I had the finished project I thought what do I do now? Thankfully we knew a few people to send it to and getting CALM on board..

Michael:…was the cherry on top.

Huse: Yeah, it was the cherry on top because when we were shooting it we weren’t thinking about it – but having their support and everything that comes with it obviously opens up the film to a much wider audience that it would never have had.

I really hope people get to see it and its incredible to have had so many people posting about it, everyone from June Sarpong to Edith Bowman to most recently, David Schwimmer, which is pretty wild.

That’s been an incredible journey in the last few days since the film came out and I don’t think we’d have had that without CALM’s help and support.

On the production itself what were some of the difficulties of filming in the flat?

Huse: Well it was their student house and it was in terrible, terrible disrepair.

Michael: It was an absolute shithole. Didn’t you see a rat?

Huse: The day of the shoot I did, yes! Do you really want people to know that? Rats running around the kitchen.

Michael: You know what, I lived there for two years and I never saw a rat until that day.

Huse: I find that hard to believe, Michael. I jumped out of my skin! A rat ran out of the door. I guess because we had no resources we were actually fortunate we had this location of their house – it was all friends helping out. I did make-up, I was the art director, and the catering as well! But we had two cameras which really helped because when people are improvising you need to get that coverage. Because you could potentially miss something.

We didn’t have an awful lot of time to shoot it in, less than a shooting day because the boys had commitments, jobs to go to. So it was really tricky. But we shot it chronologically because I wanted there to be an emotional journey, and things like that were luxuries because there was no one to answer to, no clients, nothing like that. The boys appreciated that too, the freedom to give performances.

With the performances, how do you find the line in such emotional performances, how do you know you’re getting it?

Michael: I know when Huse has told me! We basically just kept on going, we had workshopped it and knew where we needed to be energy wise. Between the three of us we had constructed this script with beats so we knew which moments needed to land, where everything needed to be geared up a notch. And because we were shooting in chronological order and trying to build the drama and how tense the relationship is between the two characters, the tension is there – we had marked the beats so explicitly in the workshops, then we were allowed to explore around those beats. For instance when I said to Jase ‘you should call your mum’, we all established that would set him off because in his head his mum is someone who put him in hospital in the first place. From there it kept building – if a moment didn’t land, it’d just be a case of going again and finding it. We knew what we were doing. Best filming day I’ve had.

Huse: With Jay’s character Jase, because he was the one having mental struggles on camera, we had to be really careful we weren’t doing any caricaturing or stereotyping of someone who is struggling. You don’t want to portray ‘a crazy person’ through Hollywood eyes. We had to be careful around that.

The whole way we went about it was a gamble but the reason it worked was because of the working environment we set up. If you have that freedom to explore and know where the boudaries are with no external pressures then I think you can get some really great results. I never shoot tons and tons anyway, I’m good at saying we’ve got it lets move on, and we had to in this case because the boys had to finish at 4 o clock and we started shooting at 10!

What do you hope people will get from the film?

Huse: Our job’s done if even one person watches it and it opens up some questions and debate and brings about some awareness around the subject. That can sound cheesy but its sincere and ultimately this drama does have a life way beyond it. Even since the film came out I’ve lost count from the number of messages I’ve had from people on social media who I don’t know saying this film has really touched me and is an important one to be seen. That’s amazing.

Michael: Actually what I wanted to get out of the film has completely changed. At the time I wanted to just work and tell a story and work in that style, but when I watched it I realised this a very tangible thing for a lot of people who don’t see themselves represented in anything. For Daniel to watch the film just a couple of weeks ago and say ‘I completely remember being in that state and saying some of those things. And Jay really did it justice.’ That was the most meaningful reception for it.

But where I’m at now with it, I’m seeing how organisations like CALM give people a place to get information and learn how to deal with mental health at any stage – it’s definitely a resource that would have helped me back then. Watching this film and then being able to click on the CALM website and being able to read about what you can do is important. Even now I’m at a stage with a brother who doesn’t want anything to do with any mental health hospital but is simultaneously having to deal with his illness. I hope that resources come out for people like me who are later on in the process of dealing with mental health. An organisation that explicitly deals with people who have been in and out of mental health hospitals but doesn’t want anything to do with them. As niche as that is, everybody has their own issues around mental health…

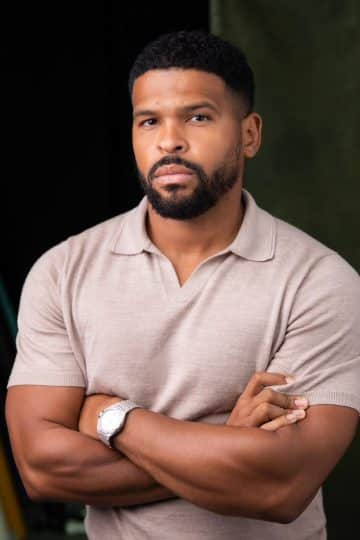

Follow Huse and Michael on Instagram:

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.