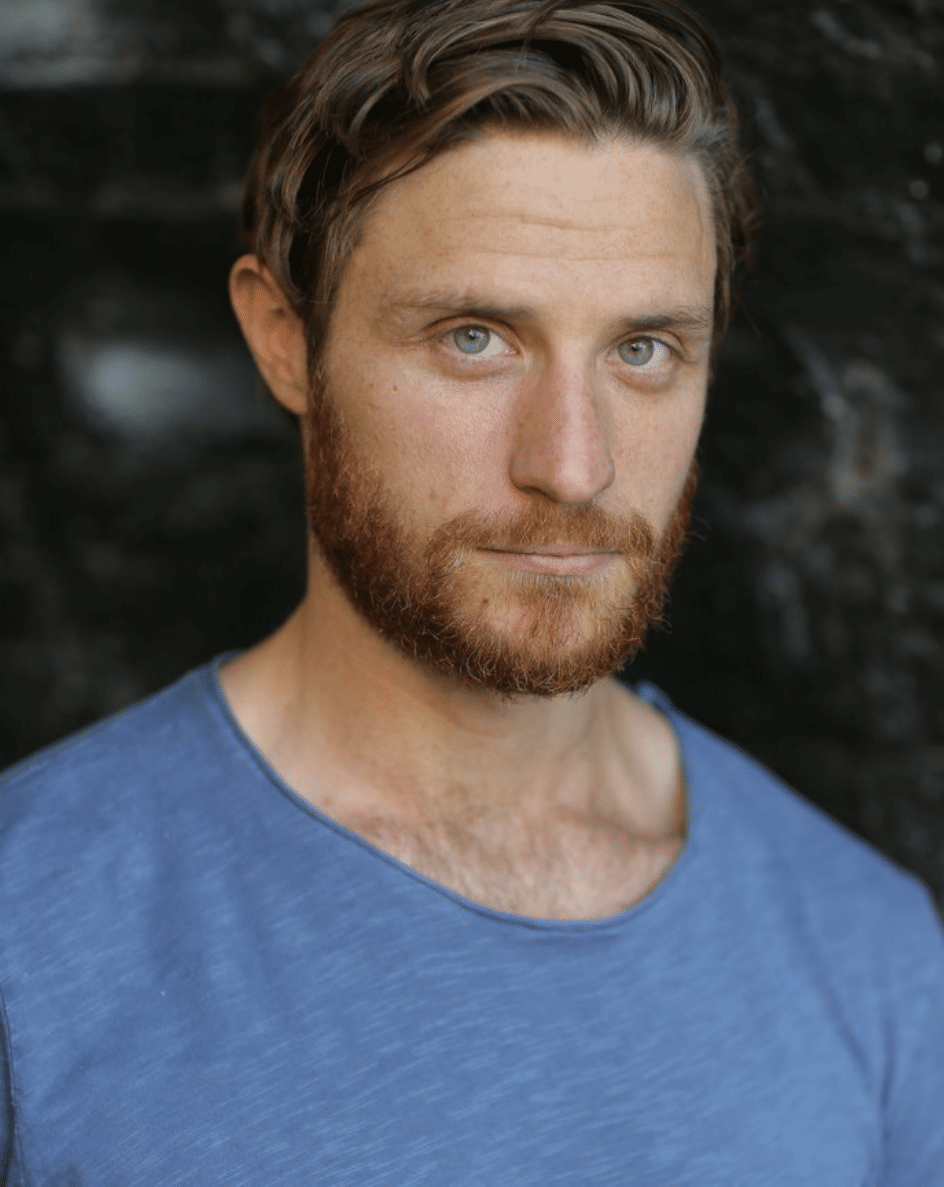

Chris MacDonald on his post-MeToo novel, The Actor

Culture

Chris MacDonald is an actor and author, and his brilliant new book is about dark secrets in drama school world and, as he writes for us here, is based on real experiences.

‘Give him what he wants’ were the words my acting teacher said to me and an equally straight male friend while we were doing an acting exercise at drama school. He kissed me. I reciprocated, kissed him back more passionately, as if to prove a point. Afterwards we were both praised for our bravery. There were twenty other students watching. My friend had started his exercise with a girl from our year, a scene where he was trying to tell his friend he loved her and I was parachuted in by the teacher to get my straight male friend to throw off the shackles, to take things further, to test himself. We passed the teacher’s test, we moved onto the next exercise. In the same term, the same teacher encouraged someone to change his exercise where he was trying to seduce his friend’s girlfriend to instead, put himself in a scene where he was trying to seduce his sister. At the time, we were between eighteen and twenty-three years old.

Around fifteen years ago while we were training at one of the country’s most prestigious drama schools, a place which has now closed its doors, we thought nothing of moments like these. If anything we thought the teacher brilliant, finding ever more ingenious ways to push us to overcome our various ‘acting problems’. We were there to be transformed from enthusiasts who always got the lead in school plays to become serious, intense, transformative method actors. The harder, more extreme and, though we didn’t use the word then, inappropriate things were, the better we felt the exercises would make our acting. We lived for it, swapping war stories in the pub, congratulating our peer for whipping himself with a belt, ridiculing one who thought he could show us him showering by washing his balls in a mug of water.

If all of us had left the school to have careers like Daniel Day-Lewis, we’d look back on these classes, uncomfortable moments we never could have said to have consented to, as important staging posts in our development as performers. But we didn’t become Daniel Day-Lewis, no one does. Of the thirty other students in my year at drama school, there’s only four or five who make their living from acting, none of whom you’re likely to have heard of. So where did this training we gave mind body and soul to, leave us after we left, not as actors, but as people?

It was this thought which inspired me to write my book The Actor. In the wake of #metoo, I started to consider how our time at drama school had affected my peers and me. I always thought of myself as one of the lucky ones in terms of how I was treated. I was a bit older than many of the others and, crucially, I was a man so I’d never thought of my being traumatised by the place but I was still there, not saying anything when girls in our year were asked to do things they weren’t comfortable with, not checking whether it was ok for me to embrace a scene-partner in a certain way, not calling out teachers having relationships with students. To do so would have been to put my head above the parapet of the transgressive, anti-establishment, mythology the school demanded we throw ourselves into. So the question I asked myself was, how far would it have had to go for me to have spoken up, how in thrall to our teachers was I, how far could my love of theatre and cinema, my desire to be a star have driven me?

And it was this provocation that gave me the seed of the story of Adam Sealey. At the beginning of the book we meet Adam on the comeback trail finishing a new movie after years in the wilderness, reunited with his acting coach and former drama school teacher, the mercurial Jonathan Dors. He’s nominated for an Oscar, but the next day, there’s a message online implying someone plans to reveal the truth about his part in a tragedy that happened at the end of Adam’s training at his brutal drama school, The Conservatoire, twenty years ago.

The story is told over two timelines. In the present, Adam tries to discover who it is that’s out to expose his darkest secret in the midst of a glamorous but gruelling Oscar’s campaign, and one in the past where we see Adam in his last year at his brutal drama school, The Conservatoire, following his journey from being a loveable working-class outsider, ignored by the teachers, to becoming the cold-hearted obsessive he becomes. I put the student-teacher relationship at the heart of the book because I wanted to explore how education and the teachers we worship can shape our lives both for better and for worse. Teachers have great power over young minds, but in the arts, these teachers often become gatekeepers too. They have the industry contacts, they are the Svengalis who can be the difference for the student between success and oblivion. It’s a lot of power to have over young people’s lives and we give it to them willingly because we believe they’re the ones who can make our dreams come true.

Adam, through giving himself to the ideological Jonathan’s method, does become Daniel Day-Lewis, he is on the verge of joining the pantheon of Oscar greats. All he had to do to get there, was completely shed his humanity. If you’d asked me during my training if I’d accept the same Faustian pact, I can’t be sure I would have said no. ‘Give him what he wants’.

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.