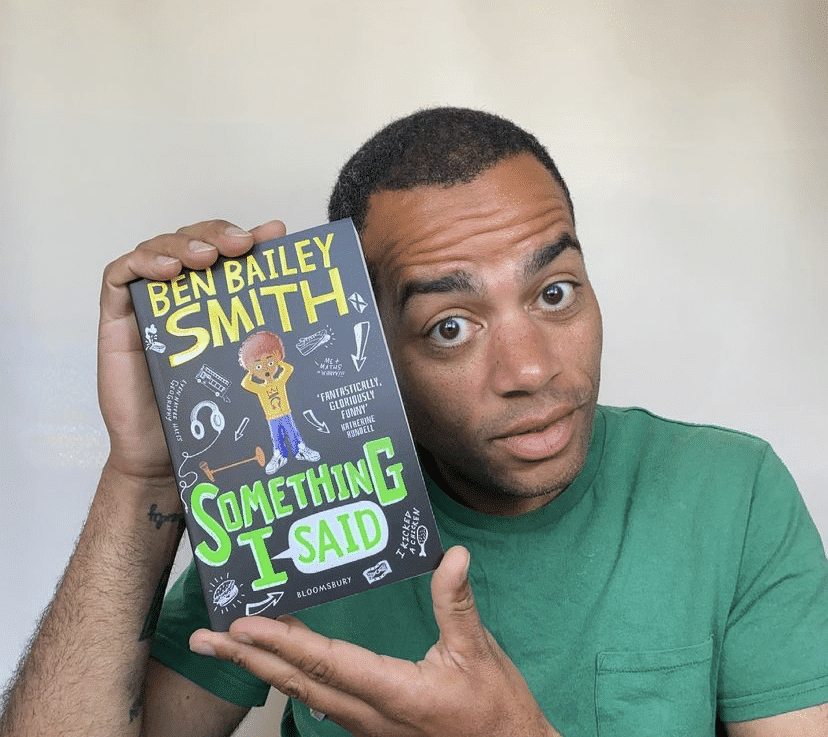

Ben Bailey Smith on his debut novel

Culture

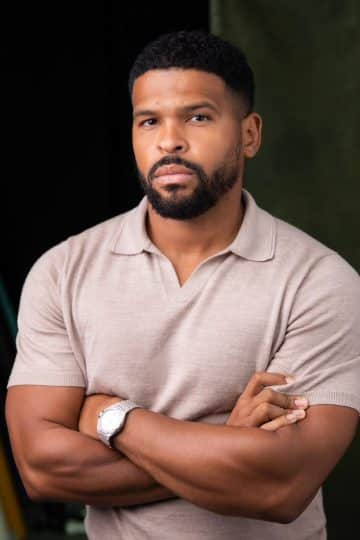

Ben Bailey Smith - rapper, comedian, actor, show-runner and now author - talks to us about 'Something I Said', your surest route to keeping the children happy for at least an hour this summer.

Ben Bailey Smith is one of those renaissance men who you can’t fail to be inspired by – a musician, of course, under the guise of Doc Brown, a gigging comedian, an actor, and the creator of long-running Bafta-winning CBBC show The 4 o’ Clock Show. But it’s his work as an author that we’re talking about in this piece: a new book for young teens called ‘Something I Said’, which is just the kind of hilarious, naughty and beautifully observed book about being a kid today, that target readers will devour (and adults too, trust us). As Ben tells it, lockdown provided him with a great chance to write the book – with his children handy for market research – but his apparent Loki-like activity is not a question of him juggling work. No, he actually concentrates fully on one thing at a time, and we can only come to the conclusion that he’s simply really good at whatever he turns his hand to, so it all takes. Hero.

Can you just tell us about Something I Said – when did you write it and what did you want to do with it?

Yeah. It’s about a 13 year old, a little guy with a big a mouth that gets him into a lot of trouble. So much trouble that there’s a lot of work he’s gonna have to do to get his life back on track. His mouth gets him into all sorts of scrapes, and one in particular that sort of changes the course of his life forever. It’s a straight up comedy mixed with a coming of age drama, and is very much reflective of that period of life, which I’m constantly fascinated about: where you’re not a little kid anymore, but you’re also not a sixth-former. You’re literally changing all the time, even physically – if you didn’t see a 13 year old for a month, they look totally different the next time you see them.

They’re actually inwardly and outwardly trying to find their place in the world, trying to work out what their identity is. I think it’s a really interesting time period to write about. So it’s a very sort of traditional coming of age story with, I guess, a twist because it’s an ordinary kid to whom extraordinary things occur.

The role of humour at that age as well seems important.

It’s so crucial. And friendships are really important. I used my teenagers a lot in order to find out things, ‘is this humour you like?’ Or ‘would you say this or did anybody say this? Would this happen?’ That stuff was crucial, on-the-spot research.

How was the writing? Did you do it during lockdown?

In terms of the writing process, I was just so fortunate, really. Like, I couldn’t work out how I was going to do it once I agreed to do it because I was really busy with other stuff. My publishers were really cool with that, they were like, ‘look, we know you’re busy, these are the sort of deadlines we would like, but you tell us if you’re having a problem…’

Obviously I did what any naughty kid would do, which is: ‘Well, they seem really nice, so I just won’t do anything.’

And then, of course, the first lockdown hit. They raised their eyebrows – ‘what are you going to do now? You can’t go anywhere. You can’t do anything else…’ And that was it. They were right. It was the perfect opportunity to knuckle down and do it.

I had a few chapters at that stage, I’d hit a brick wall and then for the lockdown period I was like, ‘This is my job now. I’m just going to get up every morning and do what I can do, whether that’s a bunch of chapters which would feel amazing or a couple of words. Or maybe I just edit what I did yesterday.’ I just made it my day job.

Did you have your kids at home as well as kind of to check things through? Because it’s certainly with my kids, the way their brains work and what they kind of find funny and what they don’t is quite different to us.

Yeah, I agree. I think humour is never something that stands still. You do get things that are timeless, I’ve shown my kids elements of things, really old stuff like the Marx Brothers and Harold Lloyd. But I’m very careful in how I pick the bits, because as soon as they saw the Marx Brothers in black and white, they were like, ‘What?’ There’s some things that are absolutely timeless, elements of humour that stay forever, but it’s like the way they are created, delivered and catered for, I think, changes constantly. So the meme culture that these kids have created is fascinating. It’s really, really funny. And I’m trying to think, what have they done here to tweak what we had? And I think it’s a similar love of one liners, clever wordplay, but there’s a visual element to it, of course, because kids are very, very visual. They’ve grown up with screens. We might have had more of an interest in words spoken or read – their interest in words isn’t less, but there always has to, I think, be a visual twist to it. I think it’s interesting how one liners and word play morphed into the world of memes.

Essentially being a kid hasn’t really changed that much, you’re just adapting to the times?

Absolutely. And everything we’re scared of as parents is just like a new version of what our parents were scared of, you know? Once it was like rock and roll, then TV and videos, then it’s video games, and it’s the Internet now. Social media.

Just on that. Obviously the last year it is a factor for kids that screen time has increased and it’s a constant battle against all that and trying to get kids reading. Is that a motivation for you?

I absolutely think reading is essential. I can’t stress it enough. And in my book I’ve sort of tried in a non-lame way to encourage kids to read more. I was never good at maths or science, geography, languages, history, RE, CDT, you know, most subjects. But I was an avid reader. I don’t know what people class as success, but I feel like I’ve made a really good living and have had an amazing career as a professional man with very little of what you’re told are the academic essentials. But the one I did have was reading. It just goes to show that if you’ve got that base level thing, there’s lots that you can do and you just hire an accountant for the rest.

What were you like around that kind of age, 13, 14. How were you coping with life then?

I was pretty shy. I wasn’t very popular, not like Carmichael, the main character of the book. One big similarity was I didn’t care about any of the other subjects, just like him. I was only interested in an English and drama, and that was it. I knew from an early age I was only interested in creative stuff. It made me be a pain in the ass in the other classes because I was clearly quite an intelligent kid who, if he put his mind to it, could easily do well in maths or science or geography or whatever. I was quite irritating in that respect. I don’t think my mum helped that much because she was very much like, ‘if you enjoy that, just do that.’ Teachers would call up and say, ‘Oh, Ben’s been messing around in Religious Studies again, and she’s like, ‘well, why is he in Religious Studies? I’m an atheist. I don’t want him to learn about religion.’ So she wasn’t the easiest for the school to deal with either.

Carmichael is more like a fantasy version of me. How I would have liked to be at school. He always knows what to say in a confrontation, or something out of blue happening. I think that’s a dream lots of human beings have. We’d all love to have the perfect cutting comeback, but normally we just think of it way later.

How did you want to build up the other characters?

I knew I wanted a really odd ball best friend, which is kind of a trope of these kind of books. I wanted an uncle that he really got on with. That uncle had to be cool, you know? But they’re all sort of amalgamation of people or fictional characters that have a bit of that about them. I just try to give them a voice that I recognise, that people will recognise, that feels real because it’s not a fantasy book. It’s definitely a real world book with real world people in it. I wanted it to ring true.

When you were a teenager, was there any particular moment in performing or writing or anything that kind of made you think I’d like to do this for a living? I might have a bit of talent here.

Definitely drama. When I was really little, I went to an after school drama club in Kilburn, called The Kiln, and I used to love doing that. I always wanted to be in the school plays. I took it really, really seriously. Anytime I was up and goofing around in front of people, I felt very excited and comfortable as well. I liked the nerves around it, whereas for a lot of people, public speaking is their worst nightmare. Some people fear it more than death, I think. I wouldn’t say there was one moment, it was just always there. And then, of course, when I left school I realised I didn’t learn anything practical. I immediately gave up. I tried to do a theatre course, an acting course, University, but every day that passed by I was like, ‘this is a waste of time. This is so dumb. I should have studied plumbing or something that would actually be useful. That will get me a job.’

I was already doing youth work part time, so I just packed it all in and focused on youth work, and I did that for eight years. It was when we were pregnant with my second daughter, that’s when I remember thinking, ‘you know what your calling is, and you’re just pretending to yourself that it can’t be done because it seems outlandish, but anything is possible. Just have a bash, and if it doesn’t work, it doesn’t work. It’s fine. At least you tried.’ You don’t want to be one of those dads who gets to middle-age and looks at his kids and thinks it was your fault I didn’t do anything. I didn’t want to be that guy, so I just thought I’ll have a go. And I never looked back pretty much.

Do you draw on any of the youth work?

Yeah. all the time. I mean, it got me my start in show business because I created The 4 o’Clock Show based on the youth work. It was set in a youth club, about the kids, and the guy that ran the club was loosely based on me. A comedy, of course. I knew someone who knew someone who knew someone at CBBC, who said to send it to them. And they liked it. They wanted me to tweak it so it was set in a school rather than a youth club, because they had Tracy Beaker coming to an end and they wanted a new Grange Hill type thing. I didn’t think anything would really happen, but they went for it, did a little pilot, and they moved me to Manchester, and I ended up writing and shooting 13 episodes. And it’s only just finished. 10 years it’s been on. Two Baftas, two RTS awards, it’s unreal. I bump into 21 year old men and women who are like, you made my childhood. And I’m thinking, Jeez, yeah, of course, that makes sense, it’s been a long time.

So it’s all directly from youth work, really.

How do you fit everything in that you want to do? I imagine it’s fairly stressful happen to juggle lots of things. How do you kind of manage your time?

I just don’t juggle because, like you say, it’s way, way, way too stressful. If you’ve got two things to do in a day, and this can be different things, like writing a book and acting in a movie, it’s too stressful because the worst possible feeling in life from a professional point of view – and I don’t just mean show business – is to feel like you haven’t really prepared properly. So when it’s your time to work you feel like I can’t do this. I can’t do it well. And that feeling is horrible.

I try never to do two things at once. If I’m acting, that’s what I’m doing. I’ll wait till the end, and then I’ll clear the decks and start the next thing, whatever that might be. And I like it when it’s something different, so you never feel like you’re on a treadmill. The tricky thing is when you go through periods of being really in demand, which happens to everybody at some stage, you hit a little purple patch – people want you to do lots of things and be in lots of places at once. You find it difficult to say no because you think if I say no, then they won’t come back and I’ll be out of work. you freak yourself out. That is a tricky time. But sometimes you just have to say no, just to be honest with yourself and say, I need this time to do this thing. Maybe you promised or you signed a contract or it’s just for you.

It’s all about being sensible, knowing your limits. So it might seem to the outside world that I do a million things, but I really only do one thing at a time. But the nature of creative output, and entertainment is that once you’re finished as an artist, the process of how that reaches the public is largely out of your hands, unless you’re doing everything yourself. Sometimes a TV show will come out at the same time as the book’s out, and at the same time, I’m doing gigs. Actually, all I’m really doing is gigs. The book was done ages ago. The TV show was like two years ago. It seems like I’m doing all these things at once, but I’m not.

What else have you got coming out this year that we can see. You’re in a new Cinderella. Is that right?

Yes, Cinderella. I think in September, Sony and Amazon. And the thing I’m shooting right now is an adaptation of Persuasion by Jane Austen, a movie for Netflix. I don’t know if it will come out this year or not – we’ll wrap on this in July, so maybe Christmas.

And what’s your next book?

I need to write a follow up to Carmichael’s story, to ‘Something I Said’. I’m just sort of floating ideas around, bouncing them in and out of my hair to see what sticks. At some point, I will clear the deck for that.

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.