In Search of His Own Mother

Culture

The story of one film-maker’s journey to uncover the truth about the mental illness and death of his mother, who he lost when he was just three.

This past week at London Film Festival there was the premiere of a moving documentary called Irene’s Ghost, which follows film-maker Iain Cunningham as he uncovers the truth about the death of his mother when he was three years old. Over the course of the film he traces the people in old photos, seek out hospital files, and drum up the courage to ask his father to open up. For his father, for reasons that become clear, has never before revealed the full story of what happened. It is a simple but devastatingly effective film, which makes use of animation to depict the memories and imaginative world within Iain’s mind where Irene existed for him.

Ahead of a full release of the not-to-be-missed film next year, The Book of Man spoke to Iain about the film, how families cope with a member having mental health problems, and his deeply felt connection to his lost mother.

How long was the journey of putting the film together?

The story of the film has been inside me for a long time – I’ve carried it around since I was a kid. I always wanted to give a voice or some sort of poetry to my mum, because it was something I felt she hadn’t had.

I don’t think that’s necessarily the truth of what I ended up finding but that’s certainly how it felt to me as a child.

My background is in television documentaries so it was a natural thing for me to pick up a camera, and it was a way to make myself start to make something creative about her, something tangible. And I think it also gave me some bravery to ask some questions of people that I hadn’t been able to ask.

In all it probably took 5 or 6 years of actual filming, but it goes right back to childhood as something I’ve been wanting to do. A labour of love, I guess.

There’s some great scenes of you building up courage to talk to your dad, where you’re just filming him gardening for ages – it’s hard for sons and fathers to talk isn’t it?

Yeah absolutely. Growing up my dad would take me to football and things like that and my stepmum was someone I’d talk to about emotional things. That set the tone for our relationship. Asking my dad about this kind of thing was not something I ever thought was doable. He was so tightly wound about it. Whenever we touched anywhere close to the subject he would be very delicate, and I knew to stay away from it really. That’s why I was very apprehensive about talking to him.

It seemed like the camera provided a bridge, for him as well as for you?

Yeah that’s exactly right. It was an excuse, a third person. It wasn’t just me and him then, it was us and this other thing. You might think something like that would make it more awkward but it actually made it less awkward. It freed us both up a bit. It gave us both a different perspective.

The story takes in so many people as you knock on doors around the town, and you get a real sense of uncovering a whole community. But has that really close kind of community changed?

I think inevitably some of it has changed from back then. Some people are living in the same houses, other people have dispersed, but the sense of community is still very strong and knocking on those doors opened my eyes to that.

The camera is kind of window onto my own life in some ways, and it was a window into my home town as well in a way I hadn’t seen before. I hadn’t realised that sense of community was quite so strong. It was nice to see that and they were all here at the premiere in London which was lovely.

Did you plan it as the story of a family and a town, or did it unfold that way as you went?

The way we structured the film was to echo the journey that I went on, and it is a slowly unfolding story. One door led to another and I didn’t know very much at all when I started the project. I didn’t really know what direction it would go in and I think it became more an exercise on camera where the focus was on me. And it’s not really what I set out to do, so that was a surprise in a way. It shouldn’t have been, I guess!

When did you make the decision to use animation in certain scenes?

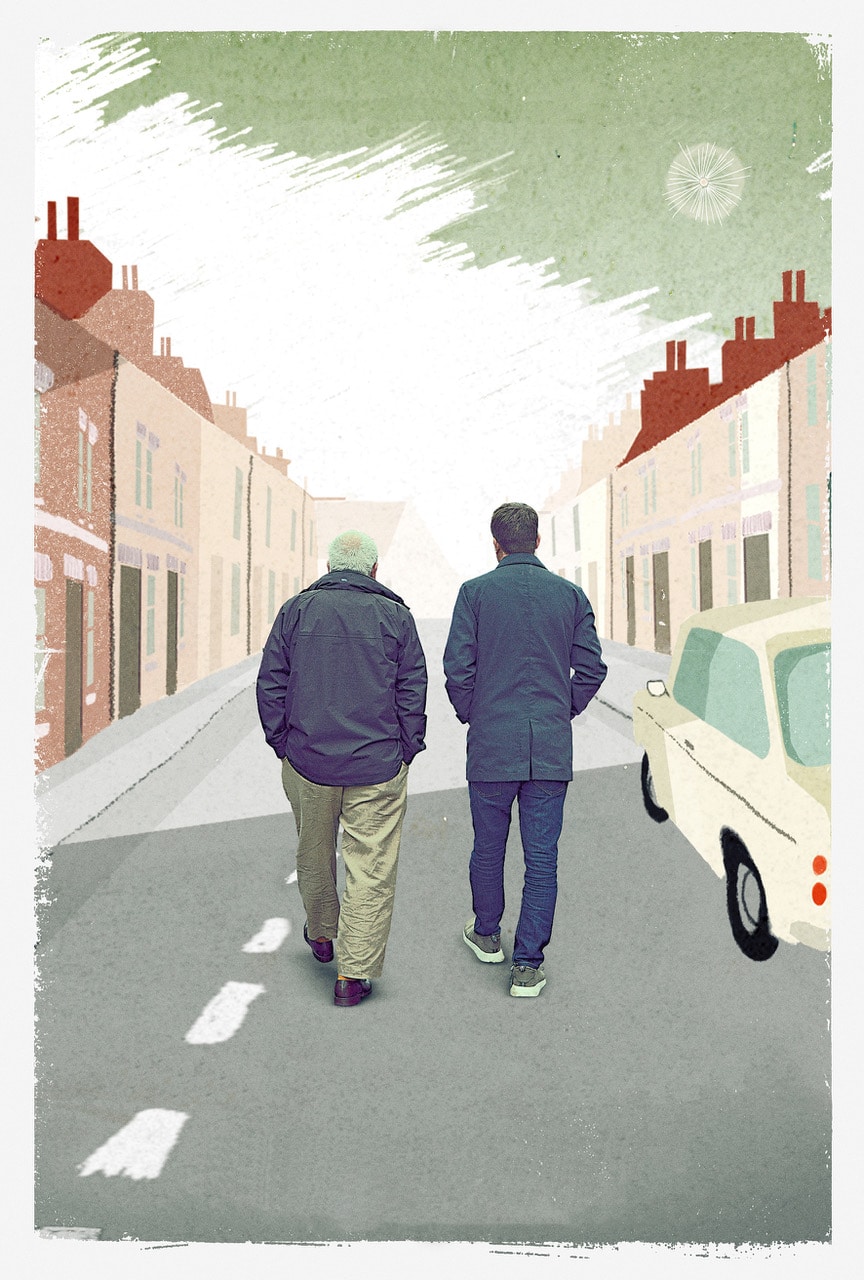

From a pretty early stage – I wanted to have animation in the project because the imaginative world of my childhood was still so strong in my mind and it’s quite hard to represent that visually. I had the baby book which was one of the connecting things between me and my mum and in that book there’s lots of illustrations which are in a similar 70s palette. So it just felt like a natural thing to do. The scene where I’m walking with my dad along the street and the animation breaks to my dad and me a lot younger, that was what I was actually seeing. The pictures were coming at me from every person that I spoke to, because the images they were talking about were quite strong and visual.

Animation is quite a playful way to explore memory of a time or a person. Also the way you think as a child is slightly wild and untethered in a way you can do in animation and you can mix some of that with the slippery truth that you find. It was a way to try and show the subjective nature of it all and also the way I think when a child loses a parent you tend to fill the space with imagery.

So I wanted to do animation quite early on but then you have to raise the money for it. It’s one thing taking a camera and filming but then using animation again it takes it to a different level.

Did you get annoyed with people? There’s that bit where your uncle says they made the decision not to tell you about your mum until you were 18, and was quite firm it was the right thing to do…

It’s a strange thing – when I spoke to my dad about my mum, just the lack of information annoyed me. But at the time I don’t think I thought of it like that, it’s only looking back that I can see how angry I was. In some ways I was annoyed on behalf of Irene and the things I felt she had missed out on. That’s a complicated thing but I guess that’s where my annoyance came from. But as I grew to understand the story more and understand my dad more and the instincts behind that, I began to understand it all.

Do you think things have changed – is it easier for families to talk about such things now?

I think there’s been change and it’s a generational thing. Its far more normal now to talk about things and share them with our families than it was for my parents, and other people of that generation. I think there’s lots of reasons why – partly there’s a luxury we have now, because our parents’ parents had been involved in the war. Certainly for their generation talking about stuff with their parents was probably quite tricky. My dad’s from a working class mining background in Scotland; it’s a different culture, a hard culture, but there’s a community and warmth there too.

So I think it is a generational thing. Certainly I want to talk to my children about everything and have talked to my children about it. You need to try and give context to their lives and their place in the family.

The whole film does have that sense of bringing your mum out of the shadows in a way that we can accept today…

Yeah, I hope so. That as what I wanted to do but – and this is something shocking I’m discovering – for mental illness, even though in the last couple of years its something that’s being talked about a lot more, I’ve met lots of people who’ve had exactly the same experience today. Children who are having exactly the same experience I had where the parent has passed away and the family aren’t talking about it, and they’ve been denied that relationship with that person. That’s something that still happens. Stigma still exists. There’s still a lot of sensitivities people still have around that issue.

There’s that idea you’re that young you won’t remember that much, but you demonstrate in the film that as a three year old you did, you really felt her loss…

Yeah I felt it. Maybe we didn’t know as much then about this that we do know now, that your early experiences have a huge impact on your mental health, and the way that you develop. And even before you’re born, when you’re in the womb, the way your mother experiences pregnancy can affect your mental health as an adult. I think we know more now about context than was known then and it certainly wasn’t talked about.

The scene when you talk to your dad and he sheds a tear – was that the first time he’d done that?

It was the first time he’d ever spoken to me about Irene in a way that was meaningful really. It was very emotional and I think you can feel the weight of nearly 40 years lifting off his shoulders. It’s not something we generally do. You see in that scene the film that we normally talk about football. And we still talk about football – I don’t want that to go away, it’s always nice to have safe ground to start from. You need to anchor yourself somewhere comfortable before you can go off and explore other areas.

Did the film bring your mum to life for you?

I mean I think I was trying to bring her to life by making the film. And from the first story I heard from her best friend about the holidays in Margate they took, and the dancing on the factory floor, she became very alive to me through those stories. And visiting the places she’d been to just exaggerated that. So I have a living, breathing relationship with her which sounds strange, but I do feel like I know her in a way that I didn’t before, and that has had a big effect on me undoubtedly.

She seemed such a vibrant character…

Exactly…she was. And unassuming and that’s what’s tragic about it and that’s the way these illnesses hit, they don’t discriminate.

How do you feel now the film’s coming out?

I’m still trying to process it, I’ve just finished it. It’s massively rewarding to hear people tell me their stories and how there seems to be an exchange. People watch it and they want to tell you their story, and I find that a huge compliment and a really rewarding thing.

I think my dad and me are getting on better than we ever have. And actually since the film he’s become far more open and receptive to talking about these things. He wants to help people by talking about himself which is something I never thought would happen. So that relationship has grown.

I hope it does encourage more conversation because sometimes you just need the permission of a film, or an article, or a friend asking a question, to talk about something that’s important to you. I hope that’s what the film can be to people.

‘Irene’s Ghost’ premiered at the BFI London Film Festival and releases in cinemas next year.

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters for a realer look at the lives of men today.

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.