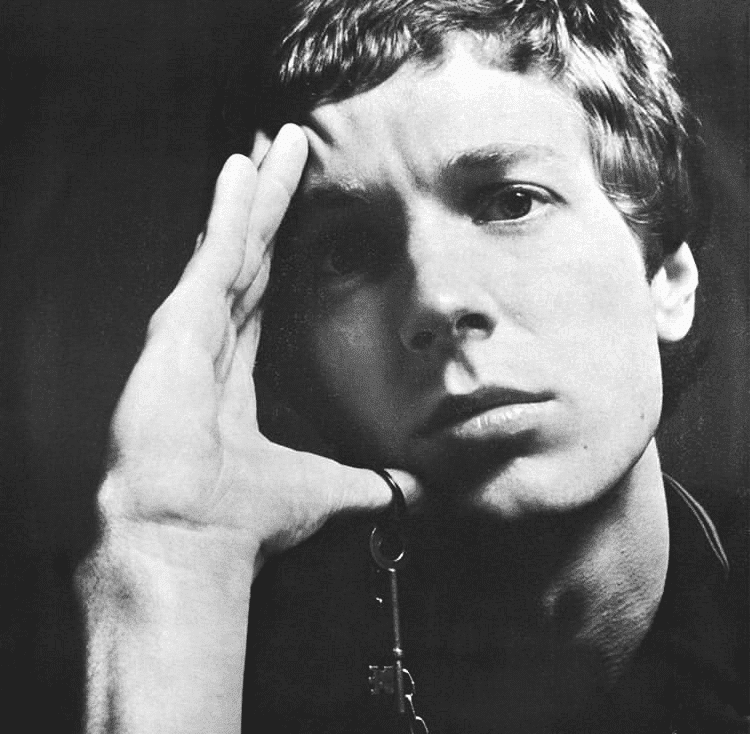

Scott Walker: an artist who stared into the void

Culture

On the death of musical legend, Martin Robinson on why the labels of reclusiveness and eccentricity should finally be dismissed so we can appreciate a truly fearless artist.

“This is how you disappear…”

The eulogies you’ll read today, about the death of Scott Walker at the age of 76, will mostly skim the well worn narrative about Noel Scott Engel, the 60s boy band member who had a mental breakdown, who first reinvented himself as a Jacques Brel inspired troubadour, then went completely insane somewhere in the late 70s and became a recluse, only reappearing once a decade for a new album of insane avant-garde industrial art music that no-one could listen to. Oh, but who found time to kill off Pulp by producing their commercial lowpoint and swansong, ‘We Love Life’.

Scott Walker the recluse. For most of my years growing up in the 90s, that was the one thing that everyone knew about him. Back then, there were no real discussions around mental health, but the closest it came to it was either related to addiction – ie Kurt Cobain was a junkie, therefore his music was weird and dark – or people who had simply ‘lost the plot’, like Scott Walker. He couldn’t take the old Fame and was hidden away in a bedsit somewhere, recording his own poundings on the dripping radiator – The People newspaper even ran a campaign to find the former heartthrob with the gorgeous voice. When he finally re-emerged in 1995 with ‘Tilt’, it seemed the bedsit radiator music recordings had been dead on. ‘Tilt’ was an extraordinary record by any standard, and terrifying. Beautiful in places, but mostly terrifying, a spare, industrial, nightmare seemingly taken from the inside of the Alien’s elogated head. Even as some labelled it a masterpiece, it was understood as impossible, bizarre, batshit crazy. He was batshit crazy.

Mental health was a bad joke, an anomaly, something that happened to weirdos like Walker, who held on for dear life as their demons took the wheel.

Yet, considering his life and career now he has sadly gone, you have to say that he was in control of this latter period of his existence, more so than being on the young star rollercoaster.

“This is how you disappear…” he said to open 1984’s ‘Climate of Hunter’, his first album sized move into abstract music; it was a decision he made. To not ignore his personal issues, his introversion, his existential dread, but to turn on them, hold them, turn them into music. He chose to stare into the areas of existence which were most troubling, where the self and society collapses. This of course meant dropping his pin-up past – been there, done that (though even then his was a sophisticated take on partying eg a Playboy bunny turned him onto Brel) – to seriously pursue his ambitions, and to do it on his own terms, in his own time. It took 11 years after ‘Climate…’ for him to release ‘Tilt’, nine more to follow that up with ‘The Drift’, but he was always working, and working hard, only slowly, deliberately.

But because he had shifted to operate outside of the usual ‘album every two years’ pop & rock artist formula, and his music was way out there, it seemed like he had broken down, rather than was busy breaking through into a new realm of musical expression.

Make no mistake, he was challenging in way only the serious artists are. A lover of existentialist writers like Sartre and Camus, a fan of very serious musicians like Miles Davis and Shostakovich, and the most challenging of film-makers like Bergman and Pasolini, but he perhaps was never respected as much as any of them were, because of his pop past, and this idea of him being a recluse/enigma/madman. He wasn’t mad, he was lucid. So horribly lucid in fact, that he could see all the horror and cruelty of the world, the dynamics of power and abuse governing human relations and governing countries, he crafted songs about totalitarianism and the Holocaust. To say his work was insane or simply eccentric, showed not just an evergreen fear of intellectualism but also a fear of dealing with fear. Particularly in popular music. Nobody called T S Eliot a nutjob.

Because it is a frightening experience listening to Scott Walker’s later albums. For many reasons, lyrically and musically, but, for me, it’s that they stare into the void at death and keep on staring. There’s no comforting melodies here, no choruses to warm you up, only a fearless cold staring, taking in the worst of human behaviour, war, genocide, torture. Hard to stick this stuff on in the car for the school run, but it can’t be dismissed as the ravings as a mentalist either, any more than the work of Kafka or Samuel Beckett should be. Just because it’s formidable and difficult doesn’t mean it should be swerved altogether, and indeed in a flimsy distracted insta-culture, a disappearance into the work of Scott Walker is a necessary thing indeed. A cleansing process, much as a horror film can be, or a punishing training session, or a spot of S&M, a frequent reference point for him…

There won’t be people weeping all day like they were over David Bowie. Walker had a coolness to him, even in his 60s pop days, an air of remote intellectualism which Bowie shared but could always temper with some extrovert charm. In fact, Bowie idolised Scott Walker, right from his 60s Brel days to his final album Blackstar, and executive producing the documentary about him, ’30 Century Man’. If you’ve never heard it, here’s Bowie breaking down crying when he’s played a birthday message from Walker:

Bowie’s withdrawal from the public eye after a heart attack in 2004, which helped regain him his mystery was most likely a combination of Lennon-esque immersion in family life in New York, and an echo of the withdrawal of Walker. And when Bowie returned with the legacy-aware, nostalgia-heavy, ‘The Next Day’, and particularly ‘Blackstar’, the music of Walker was all over it. The title track of ‘Blackstar’ alone had the epic fear of death from ‘Tilt’, though made significantly more palatable by Bowie’s genius for pleasing, shown by the funky, playful middle section, Bowie ever the melting pot for the avant-garde and pop.

No Scott Walker, no Bowie? Probably. What’s for sure is that these intertwined artists will be studied and puzzled over for hundreds of years. The work is rich, serious in purpose, and particularly with Walker you are left with the impression that he really fearlessly went as far as he could into it. You don’t want to say he suffered for his art, it’s more like his art was suffering. Pain is surely the common thread that links ‘The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore’…

…to ‘The Electrician’:

You can only speculate as to the exact nature of his mental health issues, he was certainly not a person who would talk about it. Instead, he was someone who put it into his work, and in that sense was talking about it all the time, through his lyrics and soundscapes. It’s trite to say that listening to his albums gives you a sense of what it’s like to suffer from depression or anxiety or acute stress, but if you are suffering from these things, as I have at certain points, you can feel like you’re hearing some truths in his music. You don’t exactly find solace, but you do find recognition, an abstract articulation of what you are going through – which is mostly an abstract blanketing thing – and you can even have revelations about the truly scary thoughts and experiences that may be at the heart of your own suffering at that time. In other words, it can hold a mirror to your own darkness.

Is that a valuable thing to do? When you’re down, isn’t it better that you be lifted up? Shouldn’t The Beatles be a better option, or at least some Ziggy Stardust, where you have light with the shade? Sometimes, maybe even usually. I can only speak for myself in saying that I do reach for ‘Tilt’ when I am not feeling very good about myself, at my very worst in fact. If that’s self-indulgence, well, I’d argue that the lassitude it invokes is a necessary retreat away from the world, when I’m collapsing in on myself and need to regroup. Hearing someone take his own pain seriously and in fact devote his career to staring into the dark places, well there is a comfort in that. You’re not imagining it: people can be cruel, horror exists in the world, and you’re going to die. At least someone had the balls to say it. Even if mostly people don’t want to hear it.

Goodbye Scott, and thanks for everything, every single thing.

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily bulletins for more existential dread...

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.