Shogun: like Game of Thrones meet The Sopranos

Culture

A Shogun review is simple: it's the best show on TV right now, full of love, war, culture clashes, Shakespearean intrigue - like Game of Thrones meets The Sopranos...

Shogun is the best show on TV right now and actually feels like a cultural tonic to a fevered world.

Episode 5, ‘Broken to the Fist’ was another high point in a series that gets better each week and demands second viewings to capture every nuance, every shift in allegiances, every allegorical meaning – and sure, every bit of dazzling sex and violence.

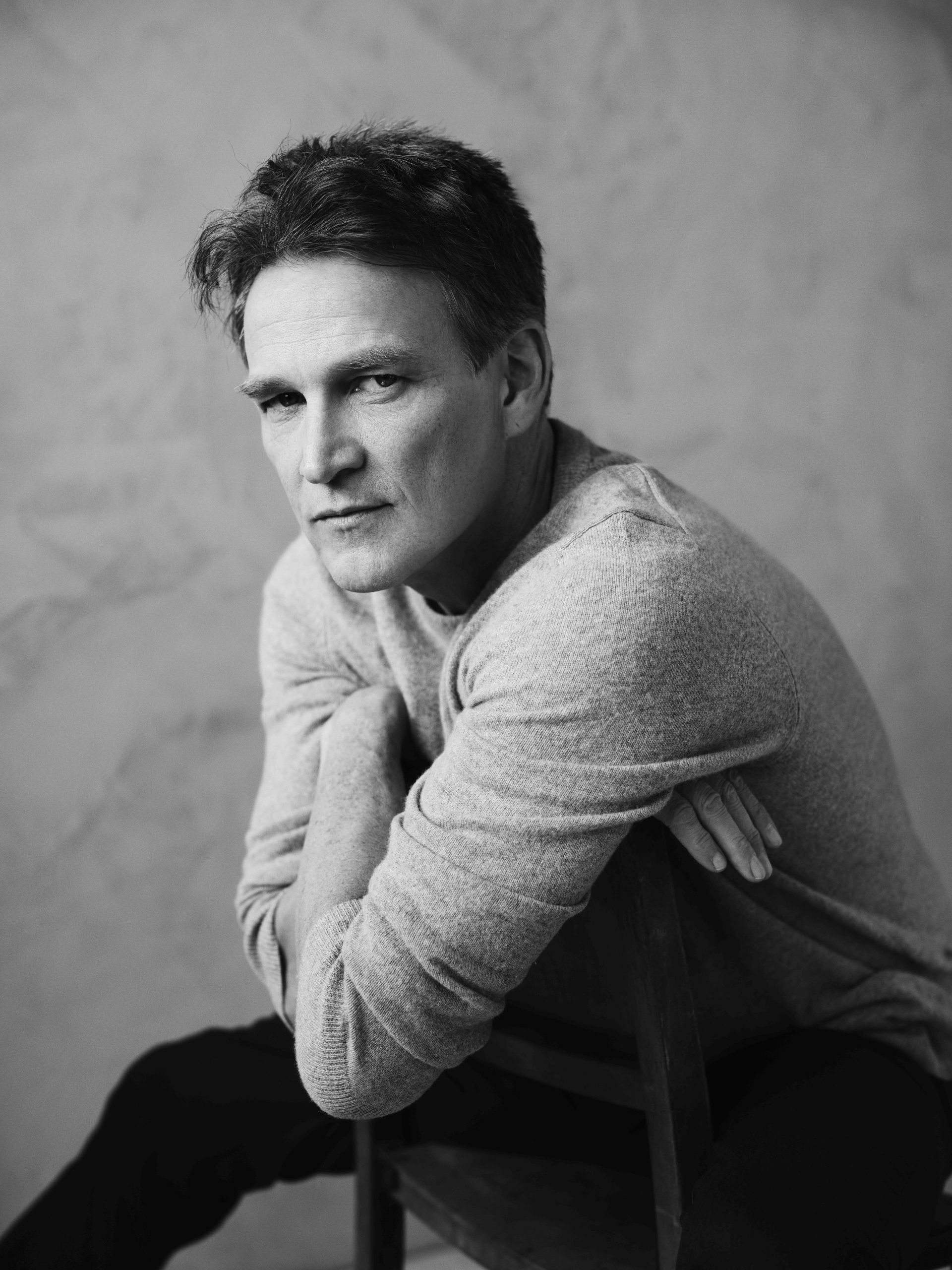

Based on James Cleverley’s blockbuster novel, which was turned into a TV blockbuster in the 80s (back when TV blockbusters were all dreadful and all starring Richard Chamberlain, which was indeed the case here), this new reboot is a Japanese-American co-production created by Rachel Kondo and Justin Marks, and is dead ahead word-beating prestige TV. Like some dream combination of Game of Thrones and The Sopranos, this has it all: spectacular settings, high romance, courtly intrigue, corruption, extreme violence, and enough life lessons and love lessons and war lessons to keep you thinking on it for days afterwards.

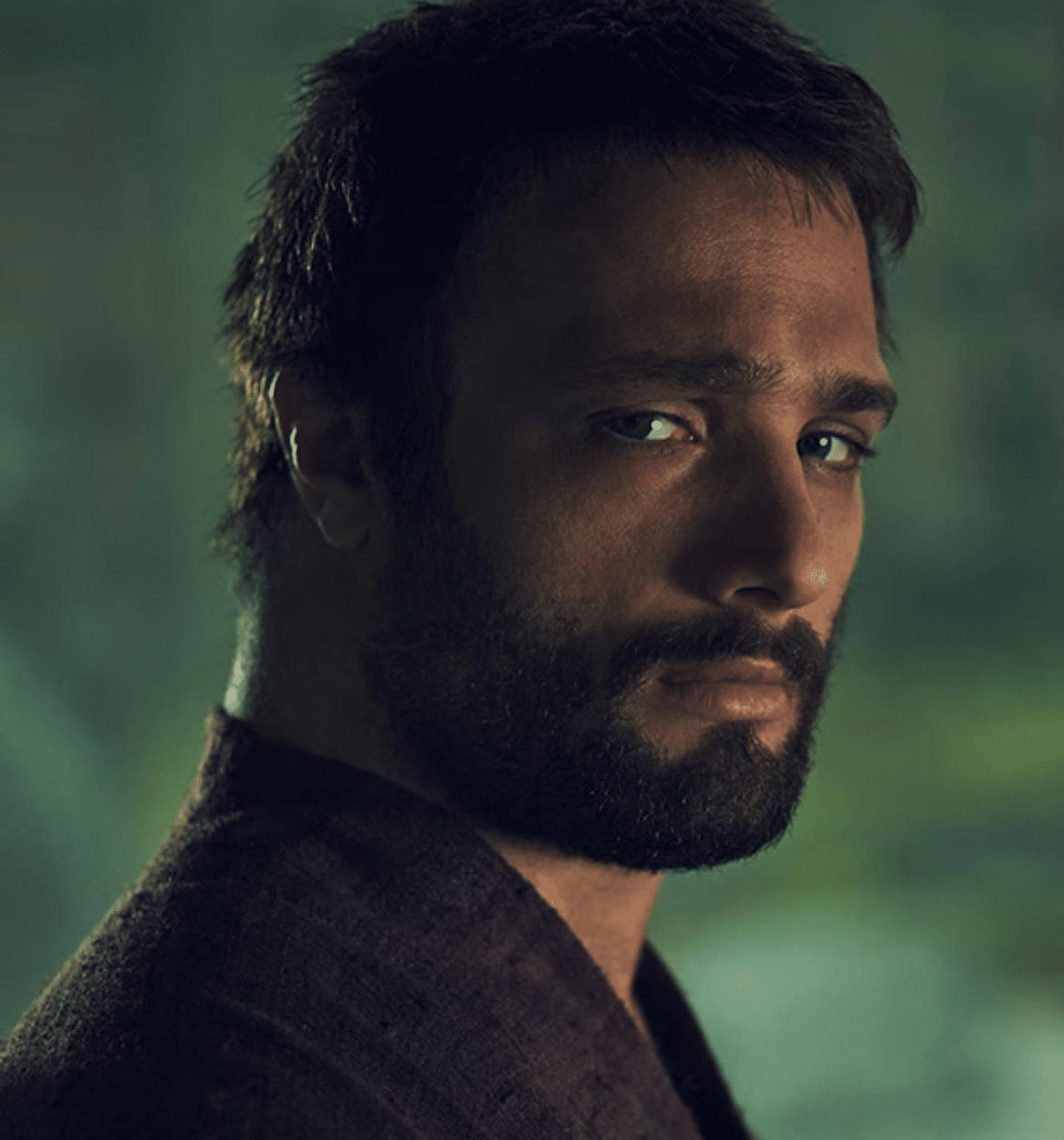

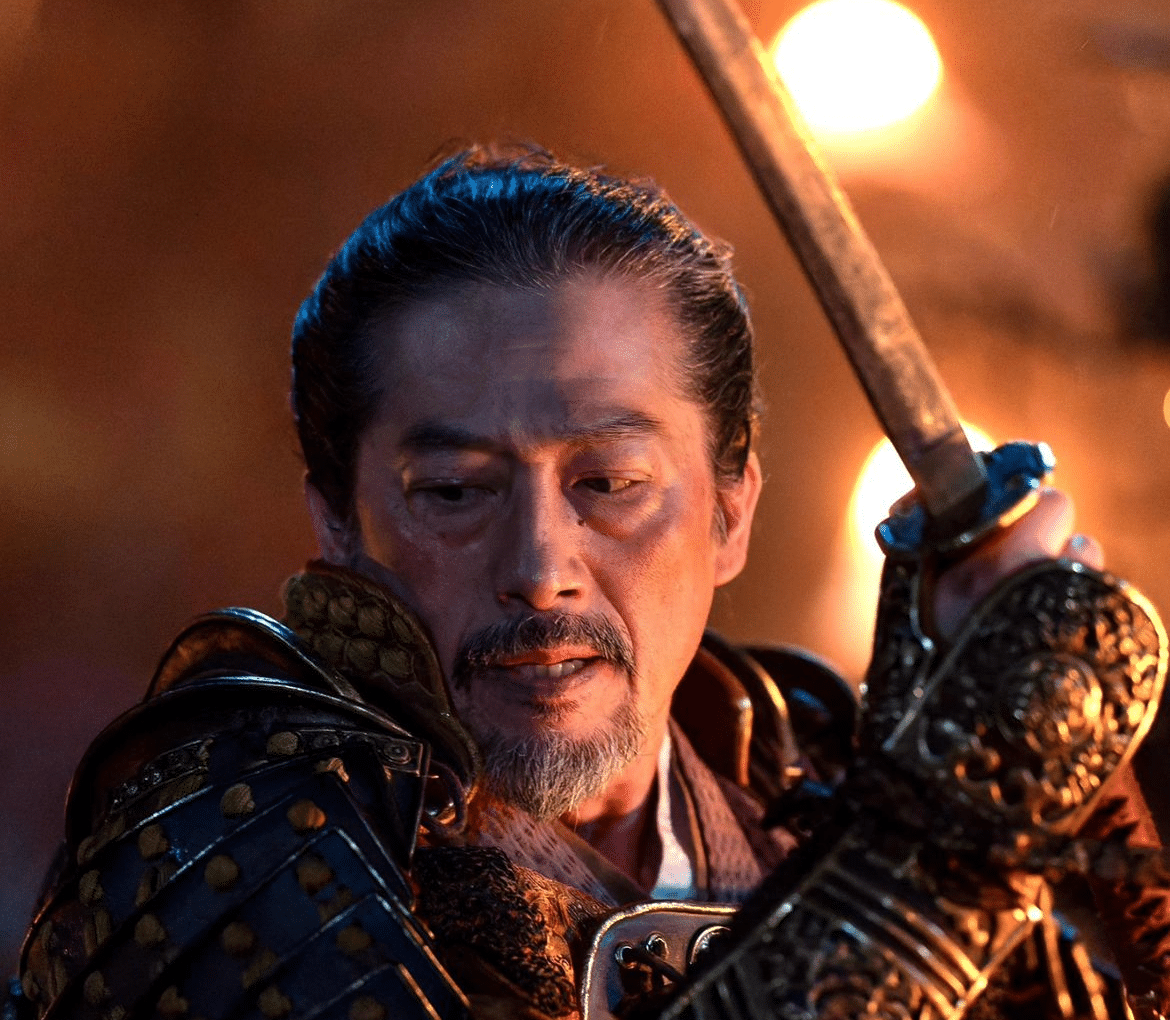

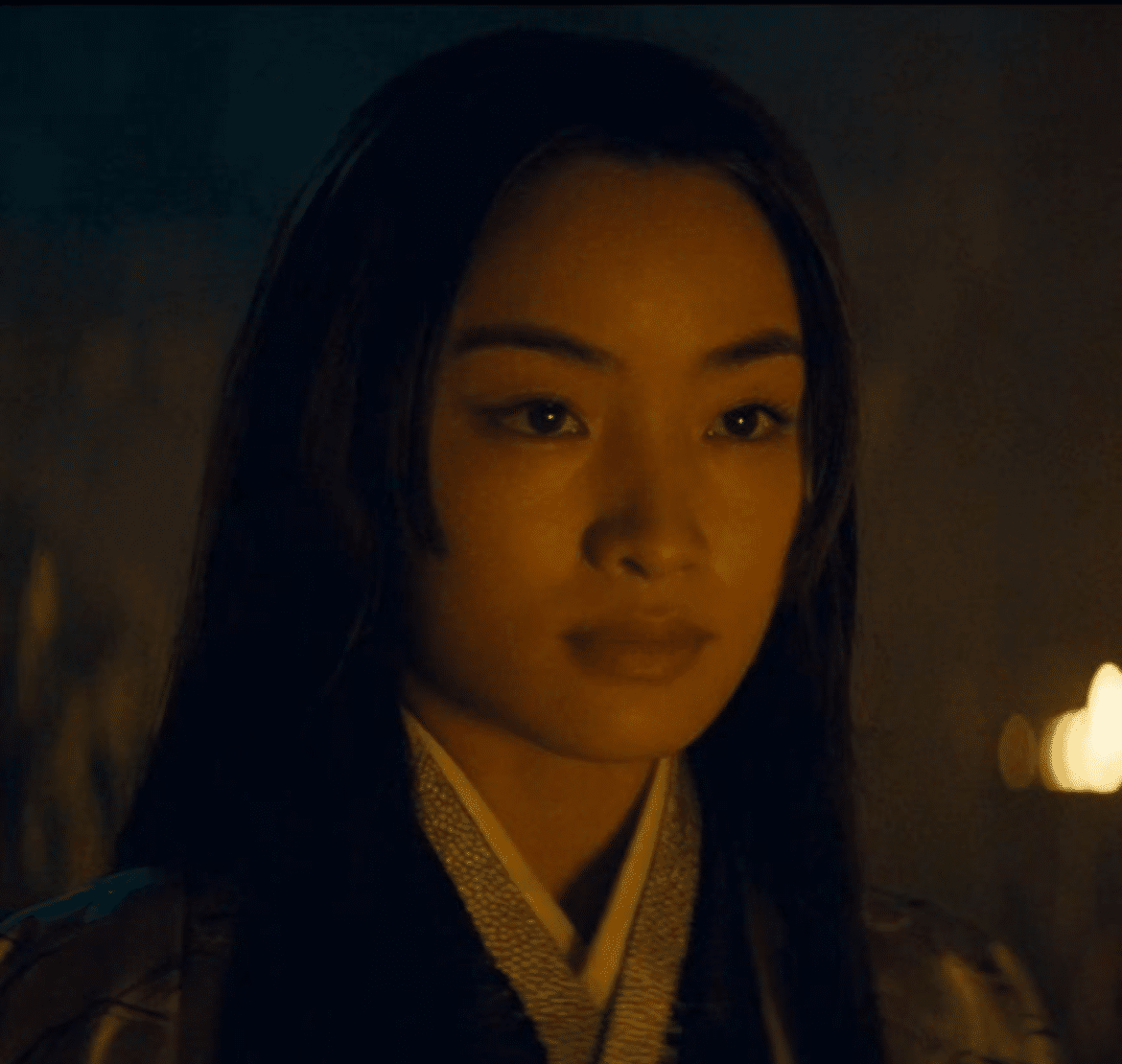

It tells the story of a gentleman pirate Englishman called John Blackthorne (a bruised and brilliant Cosmo Jarvis) captured in Japan during the Sengoku period – 15th/16th century – by Lord Yorhii Toranaga (a weighty Shakespearean performance by Hiroyuki Sanada, who also produces and as the series ‘extras’ reveal, is a real driving force on set). Between them is Lady Toda Mariko (the astonishing Anna Sawai), a woman with a disgraced family, who acts as a translator and in that role eases frictions and enables the Anjin (the pilot), as they call Blackthorne, to become a trusted ally of Toranaga as he goes to war against his political rivals.

The central pleasure of the series is the relationship between Blackthorne and Mariko, the development of their love affair, and seeing how Mariko both shields and encourages and scolds the Englishman; protecting him from the jibes of the warriors around him, whist tempering his own outbursts with choice renderings of his Queen’s English words. In her highly intelligent hands, her role is filtering what each side says through their own social language, but most particularly in guiding Blackthorne through this highly sensitive new social order, while growing close to him, since she herself is at odds with it.

This culture clash between Blackthorne and the locals (and the attendant Portuguese who have introduced Christianity to the country), is the grit of the series: both sides think the other is a savage race. He assumes those in this far away land are uneducated; they simply call him “barbarian”. And indeed we powerfully see the colonial English attitude of educating the natives as a laughable thing when put up against the formalities and social sensitivities in Japan. Though, they too underestimate him.

What we have here is a depiction of first-hand experience as a way to learn from people. Something which our digital world with its thin approximation of oneness, needs to reminded of. There’s no text messaging here – dispatch a rider if you want to say something to someone. About to be cancelled? Simply flee over the sea before they can do the damage.

This slow world is complemented by the slow deliberation of ritual, which is so central to the events. Meditative and profound, every gesture carries meaning, and every mistake or every slight can have very grave consequences.

This was powerfully put across in episode 5 when Blackthorne was given a gift of a pheasant by Toranaga. The Englishman decided to hang it outside his home in the village, wanting to cure it. His attendants, led by his consort Fuji (an increasingly nuanced character searching for life and dignity after the death of her husband and son, played by Moeka Hoshi) are puzzled, but he tells them: “If touch – die.”

Unfortunately, this is taken as gospel – and when the stink of rot gets so bad in the village, the gardener decides to take it down…he is put to death.

The Anjin can’t believe it. He calls out his attendants for not knowing the value of life. He goes to see Toranaga and says he wants to leave. Toranaga says he has no time for him “acting like a child.”

Anjin, still despairing, says his saying whoever touched the pheasant would die didn’t really mean that, “they were just words.” Mariko counters that because he said them, they had meaning. And the Anjin realises the death is on him. There is a seriousness here about life, where you have to consider your actions and words. Everything has gravitas.

Which is not to say huge mistakes can’t be made. Especially when a bit of sake is involved. And a bit of male ego.

For in Shogun, masculinity is sensitive and respectful, but it is still very macho. Terrifying violence, intimidation and one-upmanship is all part of the social code. An honourable death is the most treasured prize for a man, in this world that is so close to it (incidentally, the earthquake scene in this episode is an astonishing set-piece. No dragons, just the entire landscape shifting and swallowing up Toranaga. Blackthorne only just manages to rescue him from beneath the soil before he suffocates).

After having seen her husband, Buntaro, apparently die a few weeks ago, Mariko had grown close to, and even ‘shared pillow’ with the Anjin. But Buntaro shows up alive, fearsome warrior that he is, and is awkwardly told to move into Blackthorne’s household with Mariko – and a clued-up Fuji. Over dinner, Blackthorne and Buntaro exchange insults, though Mariko mostly tempers the other’s words. Nevertheless, they get involved in a sake drinking contest, which fills the atmosphere with impending violence. Blackthorne demands Buntaro tell a war story. He mimics firing a bow.

In response, Buntaro asks for his bow and proceeds to shoot arrows at Blackthorne’s place, but doing so in a William Tell manner, showing his ability by shooting them right by the face of his wife.

Blackthorne is incensed, saying he should show his wife more respect, as a gentleman.

Buntaro, growing increasingly mean, forces Mariko to tell Blackthorne the story of her disgraced father, but she instead tells Blackthorne how her father was an honourable man, who killed a corrupt leader but was caught and as punishment was forced to kill his wife and children, and then himself. Only Mariko was spared. Every year she asks Buntaro if she can commit suicide, which he always denies her. Confiding in Blackthorne in this way shows him her predicament – he will later call her a prisoner in the marriage; she retorts that his quest for freedom makes him a prisoner.

In the aftermath of the evening, Buntaro beats up Mariko. Blackthorne chases after him and confronts him. There is no way Blackthorne can win a battle against the warrior, but surprisingly Buntaro kneels and asks for forgiveness for disturbing Blackthorne’s household. Appalled, Blackthorne turns his back on him.

Respect, honour – these things are important, but not always given. The women in this series are possessions. But they are also clever enough to be powerful. And indeed to take the power.

What a series this is. As complex and rich as a novel, with no easy answers and no pat revelations. Hard lessons in cultural differences and in love and in life. Frivolity runs aground in this society, but boy is it fun to watch.

Shogun is on Disney Plus, new episodes every Tuesday.

FX’s Shōgun – OFFICIAL TRAILER | An epic saga of war, passion, and power set in Feudal Japan. Coming February 2024 on Hulu and FX. pic.twitter.com/geHFLIUYQf

— Shogun (@shogunfx) November 2, 2023

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.