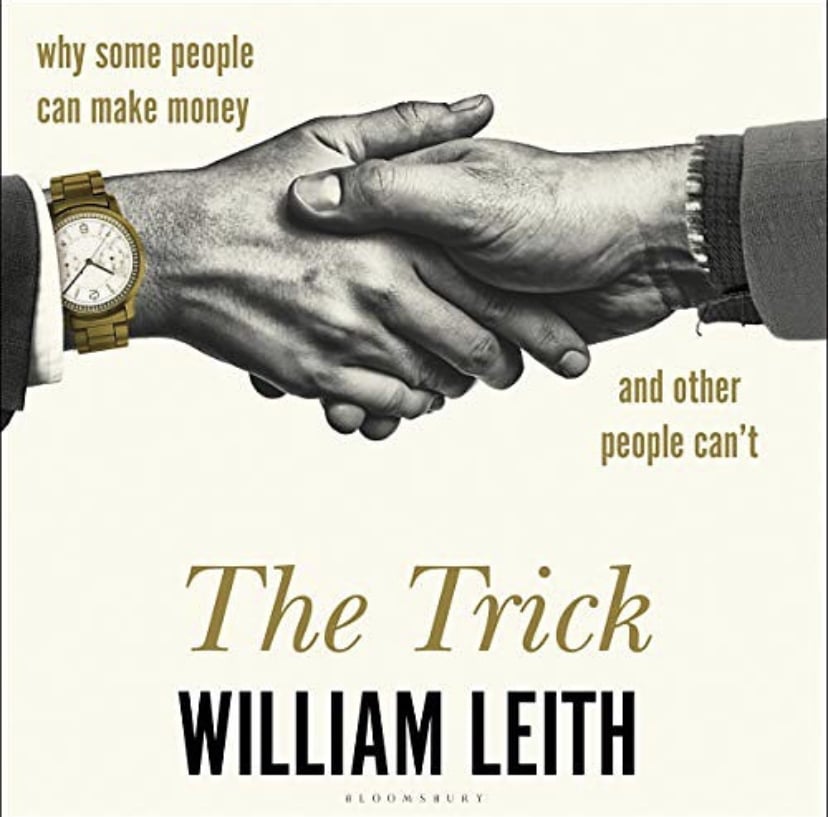

The Trick – searching for the money mentality

Culture

An extract from a brilliant new book by William Leith called The Trick - Why Some People Can Make Money and Other People Can't' in which he mixes with the mega-rich to pick up some tips, and maybe some cash.

At the station, I pay with my card. A bead of liquid is running down the edge of my eye socket. The guy behind the glass says something, he’s mumbling. There’s a slight tightening in the chest as I imagine the intimate data on my card being relayed down the wires, and, for the briefest instant, I can’t help cursing the fact that I don’t have several top-notch cards, that I don’t have a roll of banknotes in my pocket, that I don’t own my house outright, that I hate my bathroom, that I can’t afford, say, the best dental treatment money can buy.

I travel second class, and this must have some psychological significance, the fact that there are two classes, and my assumption, from the start, is that I will travel in the poorer of these two classes. Asking for the poorer seats is my default setting.

Not that I mind the actual seats. It’s not the seats.

I can feel the people behind me, shuffling and breathing, their patience filed down to the minimum, self-loathing bubbling away, fists balling, teeth grinding, you’re never far from a rupture of the social fabric. Which reminds me of a female passenger who got off the train two stops down the line, and jumped over the wall at the edge of the platform, beyond which was a wood. Had she disappeared into the wood? No. She came back with two large rocks, and threw the rocks, one at a time, at the windows of the train. The windows buckled and crazed, but did not break. People flinched. I flinched. Each time she threw a rock, the woman let out a tennis-player’s howl. In tennis, people call it grunting. But it’s more like howling. The woman went over the wall again and came back with another rock. She threw the rock at the train. Again, the window buckled and crazed, but did not break.

My card, I’m thinking.

Why do I flirt with poverty? I don’t know, but I must know, deep down, must have the knowledge, but I don’t want to let it into the conscious part of my brain, so I recycle the thought, a familiar track; why do I flirt with poverty, why do I sidle up to it, say sweet and dirty things to it, why do I invite it into my house, my life? I don’t know, but I must know, but I don’t want to think about it, but I do, I do want to think about it, just not now, not now.

Turns out I’ve missed the train that would have made for the ideal, unhurried journey. But I can still, just about, make my appointment.

The guy is handling my card, manhandling it, feeding it into a machine, feeding me, my details, into a machine, so the machine can see into the murk of my financial soul – the volatile comings and goings, the sudden cascades of pluses and minuses, the windfalls, the impulse buys – the machine knows about the time last week when I just couldn’t wait for the bus a moment longer, I’d had it, and my arm went up, and I was swept away, from the people and the dirt, the dirt, the people, the taxi feeling like an airlift, a mountain rescue, the subsequent half-hour journey costing me a poor person’s weekly budget.

The machine knows.

The machine is not stupid, it is smart, it is a psychiatrist, a mathematician, an observer and collator of tiny details. It knows. It knows me better than I know myself.

It knows about the anxiety, the neurosis, the days spent in bed. It knows about the war on alcohol – the truces and ceasefires, the skirmishes and massacres. And it knows about the secret desires, too – knows that I want to get away from the dirt and the people, that I want to live in the good part of town, protected by some kind of electrified fence, possibly even guards, but no, because guards turn on you, so just locks, please, and a lovely view, a perfect bathroom, shiny.

The despicable desires.

I’m watching the machine as it sucks and licks my card, one of its billion little tongues darting through the ether, the tip of the cyber tongue touching my card, telling the monstrous cyber brain what my card tastes like. I’m grinding the rim of one of my molars into the tooth below.

I look at the guy. The guy looks at me. He gives me a look.

The machine says yes. My card tastes good.

Yes!

Some good news. My card is sweet. Some bad news: I’m inching closer to the time when it will turn rotten. As I slide it into my wallet, as I push it into the leather slit, the card feels light, insubstantial. I see that the signature, the mark of my professional hand, has been almost completely worn away.

But I’m expecting some money! Money is coming towards me! Someone will touch a key, and the money will move towards me at close to the speed of light, and hundreds of people will try to slow it down as it moves, to touch it or hold it for a while, because if you can touch or hold it for even a moment, a tiny bit will stick to you, a few microscopic flakes, and if you spend your whole life trying to touch money as it comes past, you will collect a lot of flakes.

It will come! One day, I will be inundated. That’s what I tell myself. At this middle stage in my life, I still feel as if there is money close by, possibly even inside me, locked away somewhere, deep inside my brain.

The mechanism!

If I wanted to, I could dismantle the mechanism. If I wanted to. Anybody can be rich if they want to. That’s what Felix Dennis says. But you have to understand what he means by wanting to. He means being obsessed. By a desire that is almost sociopathic. You must be beyond ruthless. Your first victim will be yourself. You will reach inside your own head and hold the mechanism in your hands and take it apart, unravelling the wires one by one like a bomb disposal expert.

Not happy thoughts, as I walk down the dirty station stairs on this particular day, the day I will be exposed to the secret of how people make millions.

The Trick is available to buy now from Bloomsbury publishing – also available on ebook and audiobook.

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.