Return of the realist film: ‘Two For Joy’

Culture

Director Tom Beard tells us how his mental health issues and time spent working with kids leaving care, inspired his stunning new film.

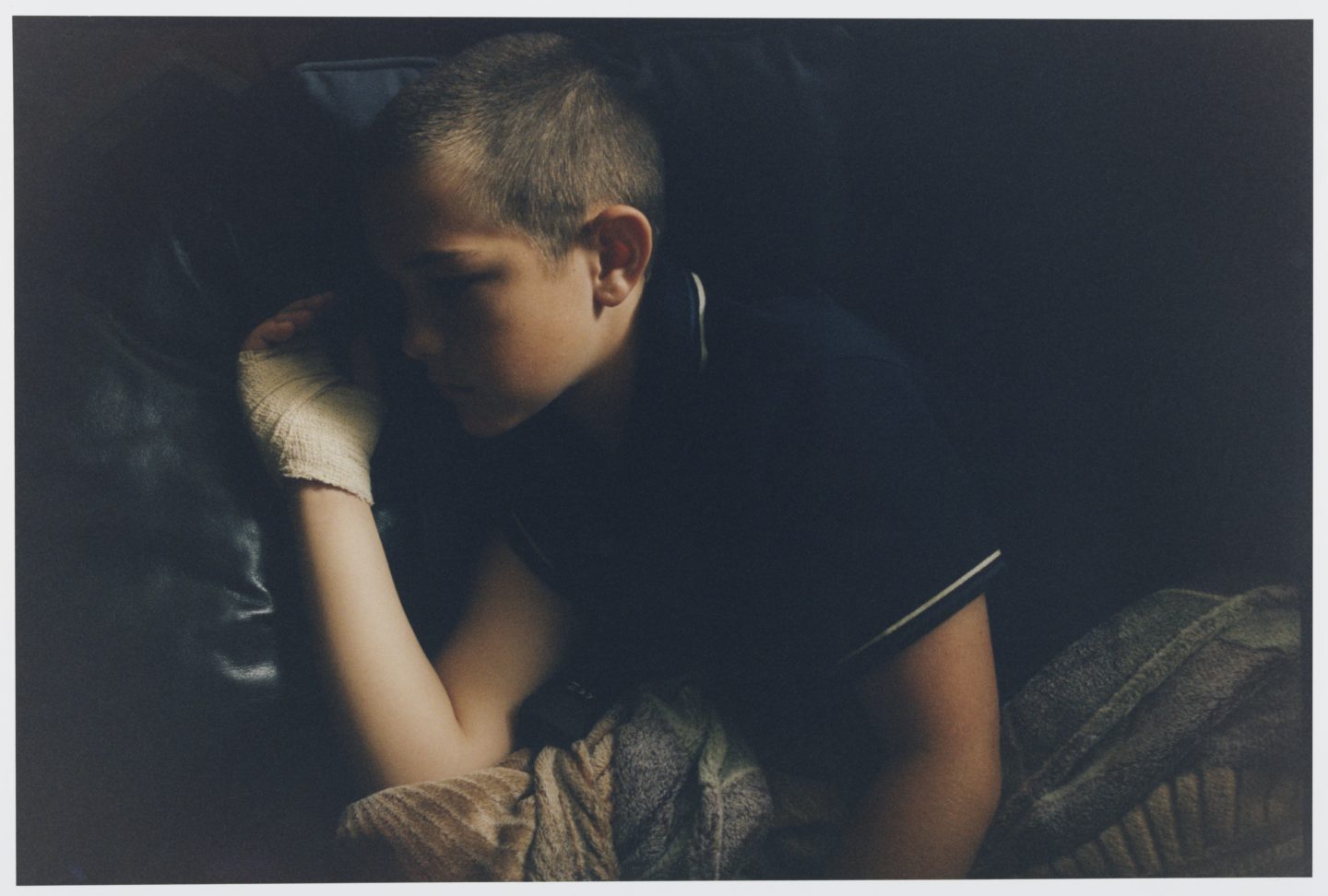

Realism is back, baby. It’s happening across all areas of British culture, shoots of reality popping up between the slabs of sci-fi spectacle, which may be a reflection of austerity or social media veil-dropping, or simply that if we see one more superhero punching one more alien in one more NO, THIS IS BIGGEST FIGHT SCENE EVER, we’ll scoop out our own eyeballs with a teaspoon. It’s led to raw narratives in music as espoused by grime and bands like IDLES and particularly Sleaford Mods, who have suddenly found they’re massive because people want some truth about life. And it’s happening in film too, as evidenced by the profoundly affecting new film ‘Two For Joy’. Starring Samantha Morton, Daniel Mays and Billie Piper and three sensational young actors in Emilia Jones, Bella Ramsey and Badger Skelton, it’s about a mother (Morton) dealing with mental illness in the wake of her husband’s death and how her daughter (Jones) has to pick up the pieces while her son retreats into his own dangerous world (Skelton, in a mostly silent performance which doesn’t stop it from being one of the great debuts). The three of them escape to the seaside where they meet another dysfunctional family and find some healing, as well as tragedy.

The film was written and directed by Tom Beard, who came up with the idea after having worked on a project with young people who had been in care. He was struck by how little support there is for children having to cope with parents with mental health problems, and how families are often split up because of it, and decided to bring it to life in a film. In its rawness and subject matter, it’s most obvious touchstones are films by Ken Loach or Mike Leigh, but there’s moments of cinematic poetry that bring it closer to ‘Ratcatcher’ by Lynne Ramsey or ‘400 Blows’ by Francois Truffaut.

There’s a moment right at the beginning where Skelton catches a fish, and then kisses it before he releases it back into the canal, and with that one image you know this ‘bad lad’ actually has a kindness to him which no-one else can see. Such affecting moments make ‘Two For Joy’ a rare thing indeed these days: a film that makes you feel.

We managed to speak to Tom about the making of the film, his own mental health struggles, and the importance of harsh reality on screen.

What were the origins of the film?

I was working with this organisation in east London called The Big House which is run by an amazing women called Maggie Norris. It’s an incredible project where they help kids leaving care to find a vocation and get empowered. I went there to cast my first short film ‘A Generation of Vipers’, and Maggie put every single one of them, the whole company in front of me. I was so overwhelmed, the things that these young people had been through and the resilience that they had.

After shooting ‘A Generation…’, I still wanted to be involved, so I tried to run a few creative writing workshops, doing a bit of poetry. I had experience in doing that at all, I felt like I wanted to try and do something to help. One of the things that kept coming up was you had children who’d been taken away from their parents because of their parents’ mental health. The children had been looking after their parents and the situation had become unmanageable. And I just thought – how could this happen? I thought it was crazy that there’s not that support network.

So I wanted to make a film which cast a bit of a light on young carers in Britain today. I met with Young Carers UK – I sent them the script to read to see how it resembled reality and they were like, ‘yeah, absolutely, you got all the themes, and the things affecting them are bang on the nose.’ That reality was really important, and I hope that doesn’t get lost in the story.

So families are split up and the kids put into care, rather than them being supported?

Yeah – really this story is about what happens when there isn’t a safety net there, and people slip through the gaps. Going through social services, and through my own experiences of mental health issues, where you’re talking to doctors about your mental health, you’re going there at times when you’re feeling different things to how you’re normally feeling. That’s how the theme of this mis-prescription came up because that was personal to me. I went to the doctors when I was extremely depressed and they gave me an upper. Not really taking into account my emotions and what else was happening in my life. And I’m bipolar, a lot of the time I’m really up and manic, so the medication they gave me just pushed me into overdrive.

Was your experience similar to the mum in the film where she’s quite bedridden and unable to do anything…

To a degree that’s my voice. “I can’t get out of bed. I don’t want to get out of bed.” And you physically can’t, you get trapped with waking dreams, sleep paralysis, a whole host of things. it was a really difficult period of my life so writing the film was a cathartic process. And Samantha was really incredible, she really understands these things, she’s been through similar things herself. You had someone who dealt with it so delicately – seeing her perform you’re like wow, she has nailed this.

Her character is not a bad person she just can’t seem bring herself to do anything to help herself or her kids.

Yeah that’s the point. There’s so much hope in this film. I really wanted to make it clear that people go through periods in their life that are dark but there is light at the end of the tunnel, there is always hope. People aren’t just a write-off. You can go through things and come out the other side and you can learn from those things and try to help others.

Which is very important to me to get that message across. It’s not doom and gloom, this is just a period in someone’s life.

How did you find your extraordinary young actors?

Bella Ramsey, Emelia Jones, and Badger Skelton. I mean, I saw them all on tape and I cast them straight off that. I went and met them afterwards obviously but a lot of film making is just going with your gut, and as soon as I saw them, I knew.

And I think you have to put that trust in your young actors, you have to treat them with exactly the same respect and don’t patronise them. I just let them free really. I never wanted to over-explain how the characters should be feeling. I’d make playlist for them and make them listen to music to say ‘this is where I imagine this character’s head to be at right now’. And it really works, and they really get into that zone. A film set can be difficult, especially for Badger, on his first film, having to suddenly jump to a five week shoot – it was scary enough for me, never mind for him. But he was like a sponge he just absorbed and absorbed everything from all the other actors and he’s just remarkable. Also, to have no lines until two-thirds of the way through the film, and still really convey how this character is feeling, this vulnerability, it’s pretty special.

How was the shoot itself?

Quite stressful. It was such a steep learning curve from anything that I’d done before. Being on music videos and commercials, there’s always an end in sight and something to cut to. When you’re shooting for 5 weeks, and shooting on film, and we weren’t shooting chronologically either, you lose all sense of where you are. A lot of it you just go with your gut. Often I wasn’t looking in a monitor, I was watching the actors perform. There’s a lot of trust in the DOP to be in the right place. The whole machine that is a film set needs to be run on trust. And conversation. Keep everyone talking.

Why did you shoot on film?

Well there’s so much depth in film. I hope it’s making a massive comeback and Kodak have been really supportive. I’ve always shot my photography on film and then when I first started making music videos it was told it’s not an option. Well why is it not an option?

So I really put my foot down and said I want to shoot as much as I can on film and all my short films have always been shot on film. It’s a beautiful medium, so painterly, with so much depth to it. If you’re trying to tell real stories you want to be shooting on something tangible. There’s a magic that comes with shooting on film, and it comes from trust I think. You’re not doing take after take after take, you’re going for the raw performance. It was literally one or two takes per shot. You’re just trusting and going with it, and you get a momentum, and I think the actors like it as well.

We wanted to shoot full frame 35mm, which is why I have that kind of border on the screen – that’s the actual frame gate [of the camera]. I really wanted to cage my actors in all the portraiture. That was very important with me and my DOP, that this is a portrait of a family. Having that frame is an important part of the mise en scene.

Was it tough having to film the really intense moments on screen?

When you’re actually making films with quite a heavy subject matter the set tends to be quite light. You’re going into these really intense moments but coming out of them elated. In my slightly bipolar way you go from deeply depressed to manically happy. You’ve got to keep the energy and confidence up.

Working on some of the locations, it was quite dreary, but I had my whole colour palette in mind. The colour palette was meant to resemble a bruise and all the changing colours of a bruise. It starts very blue then when they get to the caravan park it goes into all these bright yellows and purples and oranges. The film is about a healing process, like a bruise.

It’s the kind of film where you just want to get everyone to go see it…

You hope it can hit as wide an audience as possible. And affect people. All my work is about a response. You want people to understand and enjoy and be able to talk about it. Especially with some of the subject matters dealt with in the film. People are able to come out and talk about how they feel nowadays, especially with mental health.

I hope people can see themselves in the characters or people that they know in the characters. It’s one of these films that I want people to see it in the cinema – it should be seen there.

Why don’t you explain what happens to the Dad?

It was important to me to not have too much exposition in there. The story is not about the dad. The story is about what’s happening to the family in this moment. The father has passed away, but the story is about the present, and about this woman being unable to process her feeling in the present and the effects on her family in the present.

I don’t want to spoonfeed the audience I want to credit the audience with intelligence and to get into the characters and understand the story, because by the end it doesn’t matter what happened to the father, it matters what happens in the future. It’s about coming out of these periods and looking forwards rather than looking backwards.

But he’s there. I used the handheld approach with the camera so there’s this element that you are the fourth member of this family. It’s candid, you’re part of the family.

People have said it’s a difficult film but it’s also a sensitive film, also a delicate film and also a hopeful film. Life is difficult, I don’t understand why things always have to be sugar coated.

Britain’s got a rich history of the most poignant and incredible films which are not ones that are all sugar coated for you. It’s maybe quite telling in a country where we’re quite molly-coddled into thinking everything is going to be alright. No, do you know what? It’s not going to be alright, but if you talk about these things, it can get better.

Cinema is a good way of expressing these moments. With Netflix and things, there’s a lot genre series being made but social realism is getting left behind. People want to go to the cinema to feel. You want to be moved. That’s how I’ve always watched films.

But now cinema is about spectacle…

Not everything needs to be about Tom Cruise jumping out of a plane. And that’s it – you’ll have a whole generation of kids growing up just on that.

Growing up I had Lynne Ramsey and Andrea Arnold and Mike Leigh. Their films are the films that give you another perspective on life. And that’s so important – if you can’t make films about the human experience in this country, what are we doing? It’s an art form, and I think the art is getting lost to the money.

Do you think there is a return to realism coming?

I don’t see it being social realism in that very Ken Loach-y style. Within that genre of social realism there’s so much room to play around. Twisting things on their head. I think that’s really important. Film-makers trying to evolve the genres, still trying to get the stories done. It’s on our heads to try. Even if you look back at Bill Douglas’ films, it’s cinematic poetry, like Tarkovsky, these films are absolutely stunning works of art. I think they’re still being made but you don’t get to see them. Mark Kermode said the other day – good films are being made they’re just not getting to cinemas. They’re not getting the releases they deserve. I’ve been really lucky with this one to get as many screens as I have.

I cried twice during the film, and not at the depressing moments, but at the poignant moments…

That’s amazing that it’s touching people in that way. It’s so mad, I literally sat on a bus writing this. I can’t work at a desk, I need to be moving, so I’d just sit on buses and scribble. Rolling around on the 38 from Soho to Hackney just looking out the window and writing. From that to it hitting cinemas is just a mad process.

What, on notepads?

Oh God the amount of notepads I’ve got is unbelievable. They’re Bibles now. I’ve grown to like Muji – one of my pals told me the Muji books are made in a way that you can eventually take all the covers off and put them together and get them bound together. I’ve taken it upon myself to buy all of Muji’s A5 notebooks and scribble away. So yeah, while writing the film I did this weird pilgrimage where I’d go into Oxford Circus, buy the books from the shop, and sit on the bus home and write.

That’s great – you didn’t go digital at any stage in making the film…

No! Technology – I just don’t trust it. Technology is disposable, and film and pen and paper are not.

‘Two For Joy’ is out now, from Blonde to Black Pictures.

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.