The Wildest Film of the Year

Culture

'Wendy' is a retelling of the Peter Pan myth created in extraordinary style by Benh Zeitlin and a cast of untrained child actors on location, in the wild. We spoke to Benh to find out more about the 7 year journey to bring it to screens.

Benh Zeitlin was Oscar nominated for his dream-like and deeply affecting film Beasts of The Southern Wild in 2012. Then he promptly disappeared. Or, as it turns out, got stuck into an absolute epic new project in an brilliantly committed way that reminds one of legendary films like Fitzcarraldo, The Last Movie or Apocalypse Now: where the film-makers fling themselves into a hostile environment with a cast and crew and try to emerge with a movie on the other side. In Benh’s case with his film Wendy things were a little more responsible, due to it being a new telling of Peter Pan with a primary cast of kids. Yet, as we hope you see in this film, the principle intention of collaborating with those kids – led by Devin France as Wendy and Yashua Mack as Peter – in real locations in Louisiana and a Caribbean islands, to create a film that is truly alive, filled with the spirit of human adventure and interaction in a way that is extremely rare. Nor does is skimp on pleasing twists on the Pan myth. Wendy started as an idea by Benh and his sister Eliza, to bring the beloved story of Pan to life in a way they could get lost inside, but as you’ll see in our interview with Benh, it quickly – or not so quickly – turned into a 7 year journey which would perhaps have been the end of many film-makers. But then, Benh is not just any film-maker…

Was this film as much of an adventure for you as the film itself?

Oh yeah. When we were kids we wanted to live the story so desperately and were waiting for Peter to come take us on this adventure, but he never showed up. This was our way to, as adults, live all these things that we dreamed of as kids. That was a huge part of it. And then also just sort of more externally, we wanted to make a film about freedom and adventure that felt incredibly accessible to anybody.

When you watch this film, if you then want to go live this film, it is out there. We didn’t synthesise this world inside of a computer, you know, it’s shot on a real volcano, in real oceans and real caves. We went and lived this, and it’s out there in the world, for anybody that wants to go and find it. We wanted to bring this story closer to our lives, and really get at what it expresses that that isn’t just faraway and magical, but actually applies to how you can live your life, if you want to.

How much was prepped and how much did you allow to happen on set?

I mean, every day on this film was like, an athletic of nothing, the amount of chaos that we infused into the into the process dictated that things were never going to go according to plan. That doesn’t mean we didn’t plan – you plan rigorously, you storyboard, everything is figured out, but with the knowledge that the whole thing is going to come apart, every single day – whether it be because of the kids, or because of the natural environment we were shooting in, hiking two and a half hours to set or running the entire production at sea – you’re up against forces far more powerful than the infrastructure of the movie set.

We wanted that quality, that reality and that spontaneity, to invade the texture of the film. We didn’t want to just make the film we could imagine, we wanted to make a film that was the product of this adventure, where you feel the struggle and the danger and the chaos that the characters are experiencing in the kind of texture of the film. Even if that meant that the end product wasn’t what we sat around in a room and imagined in our heads.

The authenticity makes the special effects elements really powerful, and unexpected in a way that brings the magic back after seeing so many sort of blockbusters laying it on thick…

Yeah. We wanted to create our effects in ways that were really organic. We both have a love for sort of that era of filmmaking when it was a real magic trick, you know, it wasn’t just something that you could just create anything, you had to really think about how to create magic with materials, or find magic in nature. We wanted to bring a different type of magic that is becoming a lost art form in some ways. With filmmaking just in general, so much of how we experience worlds beyond our lives is routed through this very specific digital experience – we wanted to make a film that was really defiant of that, away from a preconceived notion of how you should experience magic in movies and in life.

With the young actors, how did you how do you find them all, and how was it directing them on set?

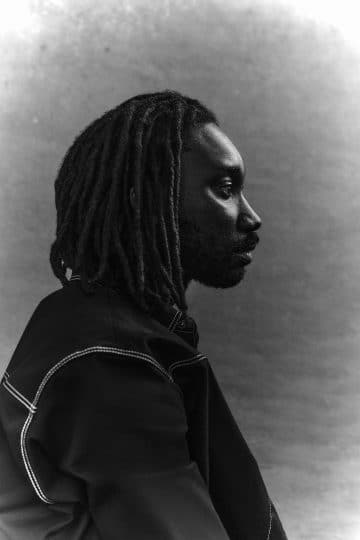

We went and looked, and this was the dream: Peter didn’t come for us, so we went out and captured him. It was a very, very, very long talent search. It was similar to how we’ve done it in the past – we’re looking for truly wild children, we’re looking for children who would run away with Peter who really felt like lost boys and lost girls. We knew that these were kids that weren’t going to necessarily show up at acting auditions, if you posted an ad in a paper. So it was a matter of really getting past the traditional channels and looking in places where the kids have incredible talent but probably have never considered acting before. Have never thought about what their job is going to be when they grow up. They’re just themselves.

On set, they couldn’t be controlled! We had to shape the movie around what they wanted to do, you know, and what they were motivated to do, what they enjoyed. Give them the space to be themselves and to be free. There was no way we were going to discipline our way to getting these performances, the kids had to really own their characters and want to be these people. And so it was a very, very long process, starting when we met Yashua, who plays Peter, when he was five years old. He was still learning to read, he didn’t know how to swim, we really went through years of teaching him everything he needed to know to be in the film, and then him also teaching us who he was, who he was willing to be in the film and what he was willing to do. What felt real to him and what felt fake. We gave them a lot of agency and power to really define who they were going to be in the film.

That took a lot of time, to adapt the script to wrap around these kids who we felt really spoke to the spirits of these characters, but didn’t necessarily have any of the training to be on a movie set.

Were you writing scenes and getting them to just take them however they went? How did it practically work in that sense?

I started off spending a huge amount of time with them. We would go on adventures with the kids, take all the kids in Louisiana, and send them off into the woods, and track them and see what happens. I’d do the same thing in the Caribbean with Yashua. He grew up in a Rastafari community, where there were like, 20 kids there, just in the jungle, running wild all day long. And I would follow them and document them and start to kind of understand how things worked inside their play. And then I would rewrite the scenes.

Usually what we would do is really not start with a script, I would start with the scenario, sort of describe the scene that I wanted. Feed the kids as much as they needed to know, have them try it out, see what happened, write that down, and then bring in the script, see what parts of it felt real to them what they want to change. It was a really collaborative back and forth. With every scene in the film, we workshopped in that way and hopefully the real spirits of these kids comes through.

It was very different from what we had written initially. What I’ve discovered doing this was that kids playing does not really involve dialogue scenes. They’re not sitting down and having an intense conversation. There are no monologues. If anybody starts waxing poetic, the kids are just gonna run away. It was more of a feeling of one game becoming the next game becoming the next game. It was like one flowed into the next. So I tried to figure out how to capture this feeling of play in the parts of the film where the kids are running wild.

We ended up cutting a lot of dialogue and replacing it with movement of imagery and feeling and music – the things that captured what was going on in the kids’ heads more than necessarily what was happening moment to moment.

Was it tricky for the kids in understanding the lines between fiction and reality?

No, they understood the thing. The characters aren’t them, they are very different people, actually. There was a spirit that connected them, but it wasn’t like they were playing themselves. And they very much understood the difference between who they were in the movie and who they were in real life.

Because it was so collaborative, it wasn’t like the kids don’t know what’s going to happen next. The movie had to be shot very out of sequence because we were moving to these impossible locations. Once we shot in a place, there was no way to go back to it, as we were in different islands. So they really had to understand where they were in the story, where they were in their character development. They weren’t really getting tricked into it. As much as they were untrained actors, we took the time to teach them how to be actors, and they really all had that sort of talent, alongside being really connected to the characters. They learned how to act and how to control their performances and jump from one part of the story to another fluidly.

With that amount of time you must have become quite attached to everyone…

Yeah. Truly. I mean, it’s your reality, and all the parents are on the adventure with you, they came along with these kids. We were all a big family supporting each other. Most of these kids are from South Louisiana, I don’t know if any of them had ever left the country before, never mind go to a Caribbean island. It was really mind blowing stuff for these kids to experience and so much of what made the movie beautiful to make was building this team with these kids and watching them go on this adventure that I dreamed of having when I was a kid. Giving the golden ticket to these kids and say, ‘you get to go to a volcano.’ It was amazing. I love them all like family. We went through an incredible adventure together.

What were some of the most challenging sequences to film?

The hardest thing we probably ever did was final scene where everybody sings. That environment was the most hostile difficult, the whole scene was shot on this outcropping of coral that’s like a breaker to the sea. It’s like razor rock. We were probably out there for five or six days and it was way offshore. We had built a base camp that was like a flotilla. From that you would get shuttled across and the kids had to be carried in, the old people often had to be carried. Just the amount of time we were on that rock, without any resources, was like a spectacular challenge. But almost every day of the shoot was like that, we were trying to find places to give the kids an incredible amount of freedom to move around, and not have to hit marks. So we were always looking for places where you can turn the camera 360 degrees and not see any signs of human habitation. To get to places like that in a place that’s as beautiful as those islands are, where everything that can be reached accessibly has been turned into a tourist attraction, it means every time you’re hiking two and a half hours, you’re building a staircase down a cliff, you’re air dropping lunch into a valley. It became almost like an expedition or something like that. Daily, that was what we were up against. The accumulation of it all was what was really challenging.

Were you getting any sort of outside pressures at all, or did you basically have to sort of have the freedom to just do what you wanted?

There was a lot of pressure, and a lot went wrong. It was a movie that was designed to not go as planned, and matching that culture, the way I’d always made films, with a completely different culture, with the studio that financed the film… they did not understand what the hell we were doing.

It was this very uncomfortable transition for us as a group of artists to work with a studio – it was an incredible opportunity, but also we were really pretty afraid of everything. You assume that your process is going to be forced to change, and we kind of designed this film in defiance of that – it was a movie that once it got rolling, there was no way out. There was no way to make it easier, we had to see it through once we got started, there was no way to turn back. And also there was like no way to find us! Because we were in such inaccessible places. We wanted it to design the movie to protect our process in a way. And then we suffered the consequences of that. Eventually knew that we had to see it through however long it took, and however difficult that was, and we’re definitely grateful and proud of the fact that we managed to get to the finish line. And kept the other world at bay, I guess. It got rough, but I hope the movie retained its spirit, in spite of some attempts to make it grow up!

Did you feel like you achieved that for yourself? Did you and your sister actually get that feeling of getting back to childhood?

I don’t know, it’s a tough question. I don’t think we understood how hard it would be and the ways that those forces would work going into it.

We felt at different times like we were Peter, like we were Wendy, there are times where we felt like we were James who was being forced to grow up by these tragedies. Every element of the story and all the darkness of the story and how these characters get pushed to the brink of giving up and giving in to what we were calling ‘the old’ – like, all of that really happened. So it certainly wasn’t this gleeful trot through fantasy land, it was a true struggle, it was a very grown up struggle at a lot of times, dealing with very hard choices.

I think that we learned an immense amount about what it really means to run away to Neverland as an adult, and it’s nowhere near as simple or clean as we thought it would be. But it but it was incredibly illuminating and incredibly powerful.

I feel like we’ve accomplished this expedition that we knew we had to go on.

What were you like as a kid, were you were you quite wild?

She was, she was wilder than me. My parents are folklorists, who run a non-profit, and we had this incredible time. When we were kids, they were writing a book about the culture of children’s play in New York City, where children find games, because they’re not growing up in nature. We had this alleyway. And there was this whole universe that we invented around this alleyway where we grew up with other kids who lived alongside there. My parents would let us run wild and their project was to document what we were inventing. So we did have this incredible support and freedom to imagine and were always surrounded by all these different cultures that my parents were engaging with, all these true weirdos, really unusual people that they that they were celebrating.

All of that, that sense of valuing people that live on their own terms, who fight for their stories and their culture, all those things were definitely instilled in us at a young age.

Do you know what you want to do next yet? And will it be a similar sort of process?

I’m deep into a couple of new projects, and I think that I definitely have been pulled back to much more small scale sizes of production. At some point, making the film like this, you become like a general, at the top of this gigantic amount of people. Working smaller scale is something that I’ve been really drawn to, and just by the nature of the last year, being at home in New Orleans, working in South Louisiana.

The new film is radically different but my process of making films if remaining, in terms of wanting to really be engaged with making films in collaboration with people that aren’t coming from the film world, whether that be the actors or the crew or just how it’s conceived. This is something that continues to be what makes me passionate about the work. I’ve never really wanted, or dreamed of being, a professional director, and I’ve always been much more about creating a project and telling story that film is suited for. And I love working this way. And that’s what continues to drive me. I’m still exploring and developing and trying to make my films better and better.

Was there any major learning that you had from, from Wendy, what was the biggest thing that you kind of learned? I guess, as a filmmaker, or personally?

There was one big thing. A lot of what it feels like in making a film is trying to figure out why you’re so drawn to the story. And I don’t think that you know when you’re inside of it, it reveals itself as you go. One thing that really revealed itself making ‘Wendy’ is that, well, I thought it was about growing up, the the anxiety around growing up, the fear of growing up that I’ve always had – but I think what actually revealed itself making the film is that this film is actually about the story of growing up. And it’s about realising that we all tell ourselves a story about growing up, and what it means and what happens. There’s a myth that we’ve cumulatively created of growing, like the Peter Pan myth, and it’s an incredibly tragic story. Like the first act of the movie is best, that’s when you’re free, that’s when you’re fun, that’s when you’re wild, that’s when you are at the peak of your beauty and your power, and then the whole next three quarters of the movie it just fades and falls apart, and you give up everything you believe, and make sacrifices for others, and you get weaker and you die.

At some point, I realised that the movie was about the fact that this is a story, and in the same way that we need to retell stories like Peter Pan, we need to retell the story to ourselves that we want to free ourselves from just living a tragedy. How do we live a story that gets better as it goes along, that ends in joy, that ends in celebration, that ends in hope. So that sort of shift in perspective is something that I realised in the process of making the film as opposed to knowing it going in and that’s always what you hope for, to be surprised by what you discover inside of a theme that you know you have to have wrestle with in your life.

Wendy is out in cinemas on 13th August

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.