Where can men go to talk?

Culture

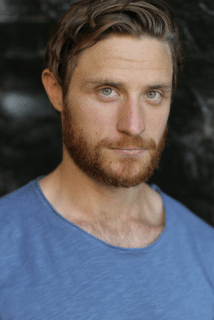

With time pressures and changing lives, it’s more important than ever that men have space to be honest with themselves, and with others. By author Jamie Fewery.

Picture the scene. You’re out with some friends, talking the night away over a few drinks without ever saying much. Sport, friends and family gossip are all on the agenda. At least half of what’s said is played for a laugh. Then, just as everyone’s about make their excuses and head home for the night, one of you says something a little more serious.

Maybe it’s a thing that’s happened at home or at work. Or they’re struggling with something and haven’t been able to find a way to bring it up, even to those closest to them. Suddenly you realise that they’ve seemed a bit quiet all night, more reserved that normal. And gradually all the pieces of this friend’s puzzle fit together – they’re not right, and they need you. It just took them a little while to get round to saying it.

I’ve certainly been in that kind of situation. Both as a friend, and the guy who’s got something to get off his chest and talk about. You might have, too. It’s taught me that men, in general, can be pretty rubbish at talking, even when we need to and ought to. Regardless of all the current media narratives and advocating for more openness and honesty, it still takes a lot for some of us to make the leap and break the laughs for a moment to reach out.

The important thing is that we are reaching out, of course. And that we’ve got space to talk, be honest and, if it’s needed, ask for help. But it’s not easy. This is why I’ve been thinking about the places men can go to talk, and how valuable they are – particularly as the way friends connect changes, and our lifestyles and social habits evolve.

The digital social group

Most of us (to be honest, I’d be surprised if there were any exceptions) are part of a few WhatsApp groups, based on various interest groups. A look at my phone shows me two for Watford FC, one for a band I’m in, a big and noisy group for organising a birthday do, and one with my four oldest friends. Plus a few dormant groups for stag dos past, the kind that occasionally flicker into life when someone wants to share a cherished memory of a non-league game in Lewes, or re-start the in joke that dominated the weekend, funny only to those who created and continued it.

For the most part, each of these groups will be jokes and memes, with the occasional bit of admin. They serve a massive purpose for just that – at a time when pubs aren’t the meeting spots they once were, and when busy lives sap time and create distance, a different way of creating lively social groups is essential. However, they also serve a purpose when life gets a bit more serious, and things need expressing.

We tend make a big thing about discussing things around mental health. By which I mean talking out loud and saying what we think and feel. And rightly so.

But the reality remains that a lot of men find this impenetrably hard. While many in younger generations are fairly comfortable with expression and self-awareness. I’d guess that older men aren’t so on board with that. They know it’s necessary at times, but it doesn’t come naturally.

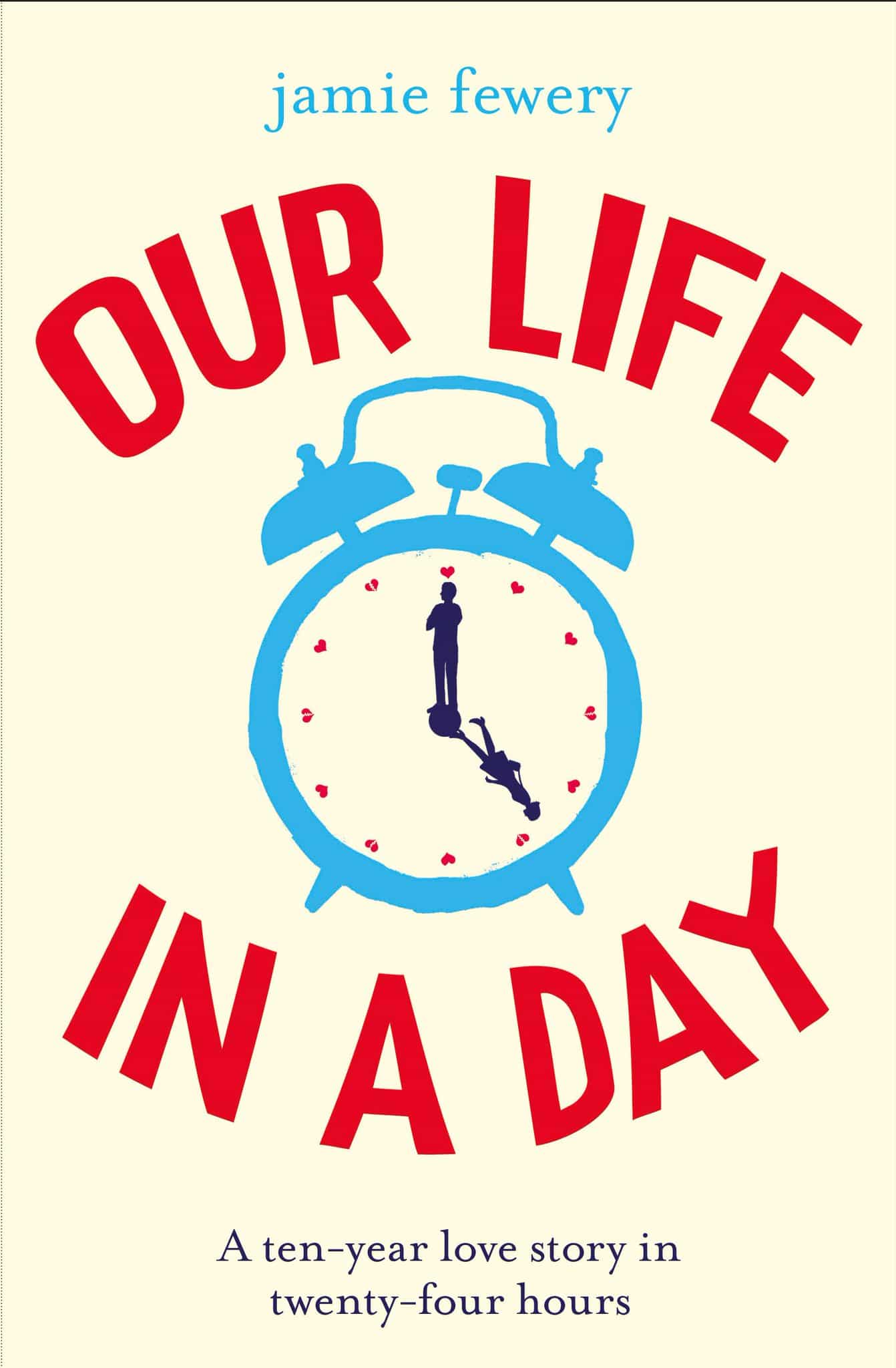

I’ve become more conscious of this myself through writing and publishing a novel that deals with male mental health. My book – Our Life in a Day – is a bit of a romantic comedy. But it also addresses some issues I care deeply about.

Tom, the central protagonist, is a man who has spent years resisting being honest about his severe mental health struggles and is continually reluctant to talk openly until it’s too late. I’m sure a big part of the reason readers have seen the character as a ‘real’ depiction is that his hesitance and silence are far more common than the frank openness many of us advocate. Sad as that is.

This is why I believe that the WhatsApp group as a place to talk is vital. Firstly, it’s private (at least if we forget the fact that Facebook can read every word of it). So any fear caused by potential exposure is limited, which can encourage the silent to share. Secondly, it’s easy to pick up the signs that someone’s not right. Their tone may shift, they might stop joining in on the jokes, or another behavioural change could reveal itself. In my case, it’d probably be replying more, given that I’ve muted notifications for pretty much all my group chats.

Whatever it is, the digital group works as an outlet in the absence of more regular, unstructured get togethers. I’ve seen it in recent months, with a friendship group that’s dispersed across the country but had to come together to lay some feelings out and remind each other of how valuable that honest connection can be. So while we’re quick to demonise the ping of the WhatsApp message (particularly if you’re sitting next to me on the train), it’s growing significance as a place for men to talk can’t be understated.

From distraction to discussion

Of course, it would be nice if we didn’t have to rely on app based meeting points as much as we do. My dad and his friends have a local where they convene for at least a couple of early evenings a week, which I’m always a little envious of. But the truth is that people have less and less time for the things that were once integral to our lives – whether that’s group socialising, hobbies or one-to-one interaction with the people they consider to be closest to them. So a virtual way of filling that void comes naturally.

However, the thing that can’t really be replicated digitally – gaming aside – is hobbies. And for that reason the sports field, snooker table or wherever else it may be has enormous value as a place for men for to open up.

The trouble is that hobbies are too easily sidelined for a lot of men. Many of us replace the time we once might’ve spent in a band rehearsal room, over a board game or in front of a dart board with more work, or engrossment in technology. Others misunderstand what a hobby is (Netflix, for what it’s worth, is not a hobby, neither is an obsession with the gym).

A good hobby is low stakes, so it’s genuinely about taking part and shared experience rather than attainment. It should also be as much about the social aspect of what you’re doing as the thing itself – a distraction, not a vocation.

In my experience, men in particular need a pretty long run up when they’re gearing up to talk about something. No matter how much the best meaning people out there emphasise the value of honesty, it remains easier to bat things away with a joke and bury that personal issue for a little longer. Shared hobbies are ideally suited to allowing for that run up.

This is well represented in fiction that deals with male hobbyists. Think of Detectorists, in which Andy and Lance will spend day after a day (month after month even) chatting about anything and everything before one of them musters the wherewithal to mention that they’re experiencing relationship troubles, or have a pressing family issue. Likewise in The Trip, where Rob and Steve will roll through every impression they can do, and will often leave one another’s company to deal with their personal demons alone for a few evenings before they talk frankly. And in ‘non-fiction’, Mortimer and Whitehouse: Gone Fishing shows two men who have spent years at the top of their profession recognise that their health requires them to do something completely other, if only to understand their inner selves a little better.

Again, I’ve experienced this. During my twenties I went through a period of poor mental health, most attributed to career and financial problems. The first thing I did was take to a football pitch with some old friends. Since then, I’ve always tried to ensure that hobbies are a part of my life – there whenever I need them. Be it cycling, football or reforming an old band, free of the ambition to actually succeed as musicians that ended up scuppering the fun first time around.

As with the WhatsApp group, what’s important is not that the important conversation takes a while to happen – it’s that it does eventually happen.

Always time to talk

It’s an odd time for a lot of men. We’re more in tune with mental health than we’ve ever been. But a lot of us still hold back instead of addressing it out loud. Writing a book about male mental health has helped me to understand that. And forced me to realise that my preconceptions about how we’re living in a very aware and open age don’t apply to a lot of people. The old ways and entrenched ideas about what men are and how resilient they should be still apply to millions who suffer silently, keeping their inner selves from those closest to them – too frequently with dire consequences.

So, as the push for greater awareness and understanding continues, it’s vital that we all give ourselves the best opportunity to talk. And that means creating space. Whether it’s digitally or in person doesn’t matter. What does matter is that we do it.

Jamie Fewery is the author of Our Life in a Day, a ten year love story, told in twenty-four hours, which is out now, published by Orion. Follow Jamie on Twitter @jamiefewery.

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.