Why men’s groups work

Masculinity

Men's groups can seem baffling but, writes psychotherapist Nick Duffell, they can provide deep, meaningful solutions to modern male issues.

I have been working in men’s groups since 1987, when I was a very green assistant at the end of my psychotherapy training. Inspired by the Woman’s Liberation Movement, as we called feminism then, men in groups represented a new and vibrant idea.

We gathered in circles at weekends, busy with profound questions: What does it mean to be a man? What kind of masculinity can I willingly identify with? How should we regulate our sexuality and aggression? What about our attitudes to women? But we also practised sharing our emotions and our lives in a way that was new to us as men.

It was a shaky start. Unsurprisingly, our group was mainly a white middle-class affair. Many were in trouble in their relationships, struggling with parenthood and missing meaning in their lives. But then, tragically, one member ended up killing his wife in an argument and being sent to jail. Visiting him in HM Prison Cardiff, it was clear to me that posing these questions meant much more than the luxury to indulge our angst, or hug trees, as menswork is often characterised.

Years later, the same questions are still relevant and alive. The artist Grayson Perry declared:

‘We men ask ourselves and each other for the following: the right to be vulnerable, to be uncertain, to be wrong, to be intuitive, the right not to know, to be flexible and not to be ashamed.’

I argue that if men claim such rights, then we also have parallel responsibilities. These are to out-grow our traditional training that keeps us immature and risks earning today’s toxic label. The job involves learning to feel our emotions and express them so that we avoid the three traditional male mistakes: exporting our frustration or powerlessness on someone else, clamping up about things that really matter and retreating from relationship into work, distractions or addictions.

If anyone needs a purpose for this endeavour, how about: so that we learn to live decent lives and to provide models of masculinity for younger males to willingly identify with? But how can men acquire such learning? It is certainly near impossible to do on your own.

It’s a complex question, and there is good and bad news. Males learn bad habits in groups, at school, in their peer-group, at work and generally in male-led institutions – look at the police, at the moment. The good news is that if bad habits are learned in groups, the good ones can be too.

Supported to explore identity issues in therapeutic menswork, men can safely try out sharing feelings, practising empathy and supportively challenging each other. They are then better placed to stand in the eternally difficult world of relationships and can challenge patterns of defensive or dominant masculinity back in their own communities, becoming a force for social change.

Some may argue that individual therapy can bring about such learning; but I don’t think it has the same power as a facilitated group. Besides, the one-to-one therapy encounter may not be an ideal format for men. I am not the first to propose this.

In a forum for clinical psychologists, Andrew Plemper wondered ‘Are men less willing to engage in traditional talking therapy because therapy has been feminised?’ I think ‘feminised’ carries an unnecessary charge, even if most therapists are women, but I agreed with the bulk of Andrew’s conclusions. Wading through the kind of research-based arguments that universities require, however, I didn’t enjoy his way of tackling the problem. For a start, my experience at UCL taught me that academic research is never free from interest or bias.

For me, the current views on masculinity, laden with simplistic or scientistic assumptions proliferate because most people are looking through too narrow a lens. Sandwiched between the partisan mindsets of a Cartesian medical model and ungrounded postmodernism we cannot get proper answers to the complexities of gender and identity. In fact, if we go along with this narrow-mindedness, we find we abandon embodied experience and give our power away to academics and angry social-media trolls.

There are at least four vital further approaches or lenses that are required, in my view. Space dictates that I only briefly point to them here.

The Imagination

First, there is in the uniquely human experience of self-reflection and awareness of death that gives us the imagination. And imagination appears to be somewhat gendered, in that there is a quality of framing things, in responding to and seeing things which is distinctly male or distinctly female which extends cross-culturally. For example, even with the briefest contact on widely different contexts such as pre-industrial indigenous cultures, men (and women) find that there are resonances between them which are at least as powerful as their current cultural references. This connectivity can be an ally in a facilitated gender group.

A gendered imagination defies the culture-only explanation: hardly surprising, since culture is always on the move – we hope for the better – and therefore ephemeral. I do not believe it is explainable by the claim of the universality of Patriarchy; this is accountable for much harm but has now achieved mythic status (like God or the Devil) and is therefore becoming a projection.

One facet of the male imagination seems to be that it prefers (three-way) a triadic to a dyadic route; so the intense one-to-one relationship, therapeutic or otherwise, is not always best. For example, in the early nineties when the Mythopoetic Men’s Movement was alive and met in large gatherings, a man seeking reconnection with an absent father (a common experience in those days) was advised to perhaps take him to a football match or go fishing. A common activity to relate through (triadically) can allow a connection to grow; a one-on-one demand for intimacy (dyadic) can feel all too much, like a confrontation. This is another reason why one-to-one therapy is not ideal for many men.

The Unconscious

The second lens is the unconscious, whose presence the founders of psychoanalysis demonstrated over a century ago. The unconscious has a collective dimension, as C.G. Jung taught, and influences through cultural accumulation of existential experience going back to the beginning of time. Jung’s Collective Unconscious is a pan-human expression of the imagination. So, there is something very ancient that is stalking us; it is much wiser than the current cultural fashion for framing things.

The unconscious has its own dynamism; it favours curiosity and mistrusts certainty. It wants us to evolve; it knows we are capable of atavistic bestiality (let alone toxicity) but invites us to live by deeper values. In the constructed safety of a men’s group, members can acknowledge their shame, their fantasies and longings and get validation or guidance.

Soul

The third – allied to both the previous – is the experience of soul. By soul I don’t mean a product of belief – something eternal that defies death – but rather a quality of personhood that makes meaning out of experience, and particularly out of suffering. Here the medical model – and, I’m afraid, both clinical and research psychology – gets stuck in a binary view of what philosophers call the Body-Mind Problem. CBT is no use to the soul; depth psychotherapy can be, whereas a committed men’s group is expressly useful to chart the journey from confusion through suffering to meaning.

Worse, medical-model-based psychology seems addicted to the medicalisation of distress. The word mental health is everywhere nowadays even if social support is dwindling. Recently, I have come across widespread self-pathologising and an apparently acceptable notion of mental health diagnoses bolted on to people’s identity. It is clear that the original motivation here is to help people feel ok if they are not feeling good, but it is now out of control, fanned by the media and celebrities, including, in Britain, by the junior Royals.

Energetics

The fourth field has to do with the energetic nature of the human being, which is a bridge way too far for the medical model. Rooted in ancient body knowledge, it developed more in the Orient than in the West, with precise maps of chakras and meridians. In its gendered application it has more to do with the genitals than the brain. This is very unfashionable. The progressive news channel Byline Times columnist John Mitchinson recently proposed that ‘our brains reflect our lives, not our genitals’, building on our current knowledge that brain differences between sexes appear to be negligible and following the fashion that mind always trumps body. But how, without studying venerable Yoga or cutting-edge Sexual Grounding Therapy, would a journalist understand the somatic complexity of the dynamic interplay of receptive and penetrative forces within the genital energetic centres?

This is another important dynamic that gender groups can facilitate. For example, the traditional male training to be always penetrative – in work, as in sexual relations – prevents men from developing their receptive, vulnerable sides, as many theorists suggest. At the same time, I regularly meet men born post-feminism who report difficulty with their ‘thrusting’ energy. This topic requires much trust to engage with – it’s dynamite in the current gender battle-ground – so it goes unconscious or re-emerges in resentment-fuelled reactivity, like the Andrew Tate phenomenon. Bodywork to experiment with this cannot be successfully done in individual therapy: it needs a good men’s group.

After 35 years in the field, I am convinced that therapeutic men’s groups are the best medium for men to evolve, to learn emotional intelligence and relational skills. But perhaps that’s just my ‘confirmation-bias’?

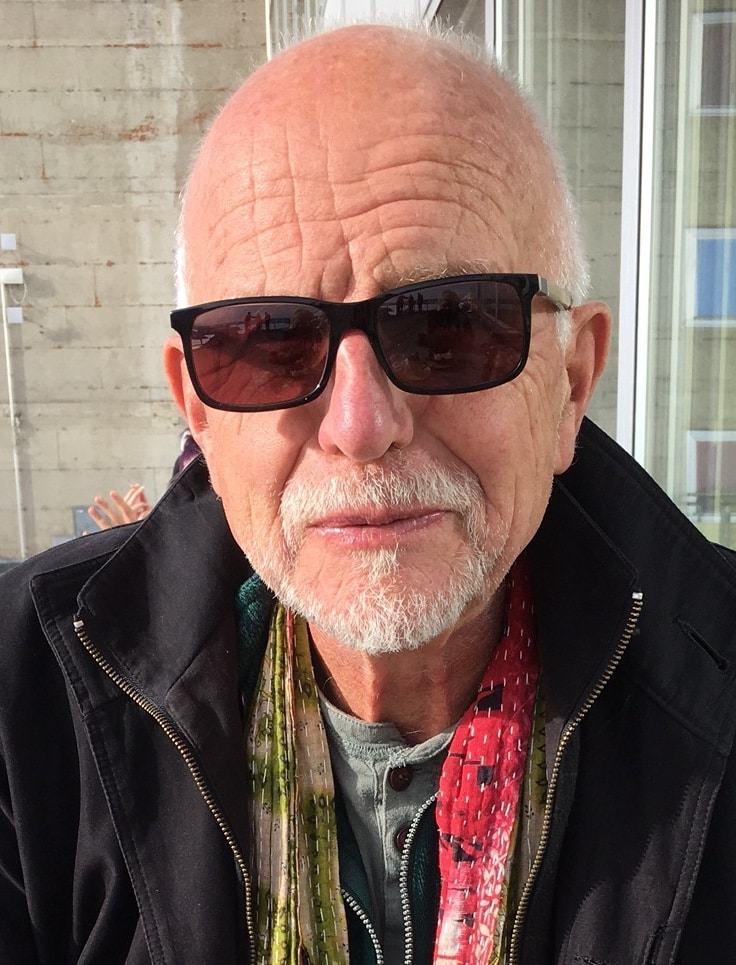

Bio

Nick Duffell is a psychohistorian psychotherapy-trainer, and author whose books include The Making of Them, Sex, Love and the Dangers of Intimacy, Wounded Leaders and The Simpol Solution.

His ‘Evolving Men’ residential retreat starts June 9th in Wales, psychohistorian see www.genderpsychology.com; workshops for ex-boarders are listed on www.boardingschoolsurvivors.co.uk

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.