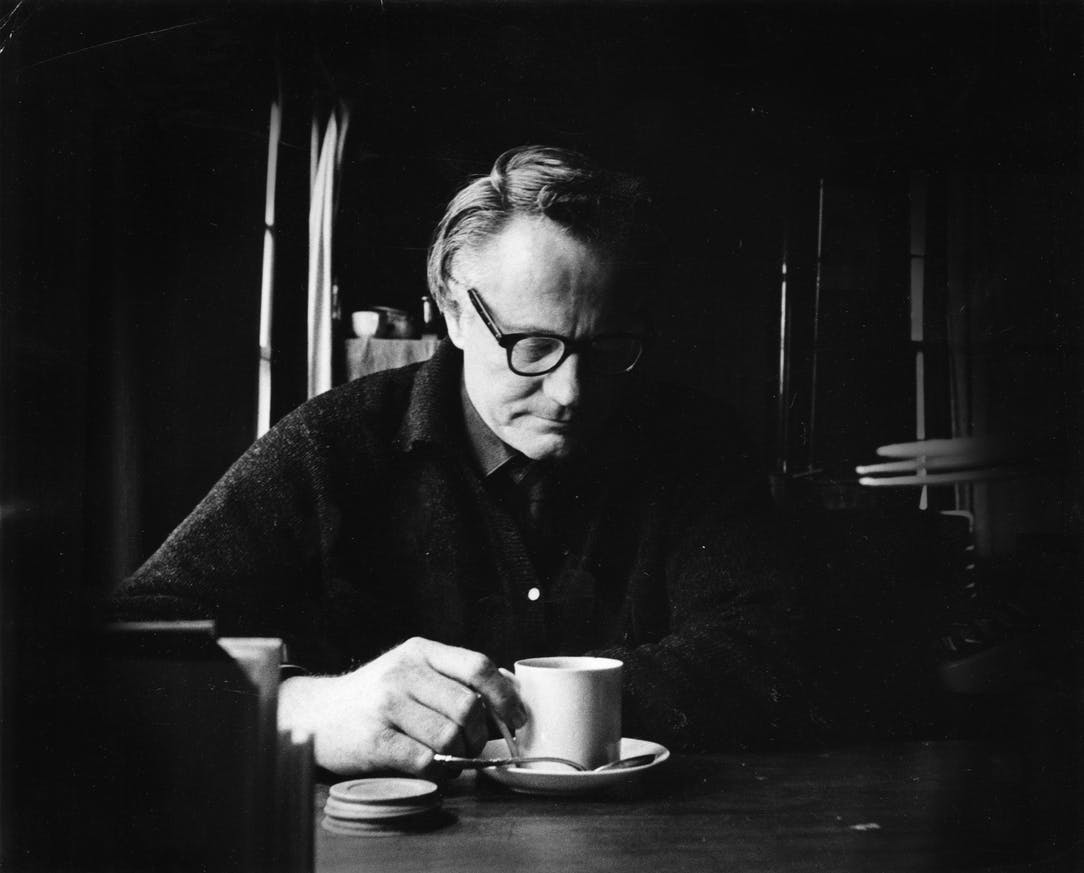

Robert Bly has died

Masculinity

Nick Duffell - psychotherapist, psychohistorian and men's group facilitator - writes about learning from, and continuing to learn from, the poet and activist, Robert Bly, who has died at the age of 94.

The American poet Robert Bly has died. I feel grief and gratitude.

Bly’s work has profoundly influenced me, and he generously endorsed my first book, The Making of Them[1], as did David Cornwell (John Le Carré) who has also just gone. The actor Mark Rylance wrote:

“The most profound thing that an elder man can do for a younger man is to mentor and encourage a particular gift.” [2]

Bly properly articulated the notion of mentoring, now gobbled up by the corporatocracy, but what he really valued was that the young should experience the blessing of older men. I did from him, but when I approached Cornwell with a similar sentiment, he was having none of that touchy-feely stuff and cut off contact with me.

So, it’s an immense privilege to tell you some things I received from the great man, but first a word on grief. Grief is not just when you lose someone: besides, Bly was 94 when he died and had been through Alzheimers for the last 12 years, so it may have been a blessed release. But grief is an aspect of experience that takes us over at other times, for example when the world seems so crazy and disappointing, as it seems to me currently.

Bly taught that holding grief, rather than indulging in self-pity, has value and is a skill. It demands commitment, whereas apathy or bitterness is a turning away. Bly once wrote that bitterness can be avoided by holding what he called the “grief pipe” between one’s teeth, in an image recalling the Native American peace-pipe, hinting at the determination needed to come through the process towards acceptance.[3] If grieving is faced, without cycling back through the previous stages, as elaborated by Kübler-Ross, it can – the poet knows – create space within the psyche, and this can become transformative.

Grief, love, and joy are Bly’s main themes. If you have never heard him reading, you’re still in for a treat because there is plenty online. Here’s an excerpt from one of his Ghazals in English:

I don’t mind you saying I’ll die soon,

Even in the sound of the word soon

I hear the word you

Which begins every sentence of joy

…Ah, you’re a thief the judge said,

Let’s see your hands

I showed my calloused hands in court.

My sentence is a thousand years of joy.[4]

In the early 1990’s, I had the privilege of learning from Bly along with James Hillman, Michael Meade, Martin Prechtel, Malidoma Somé and Marion Woodman. Later men’s meetings featured Rylance, now an Oscar-winning Sir, and Dudley Young, author of Origins of the Sacred. The influence of these men and these meetings, where of course I met and interacted with dozens of other male seekers, was profound.

Though not overtly political, a young Bly stridently denounced the Vietnam and Iraq wars and championed the First Nations. A poet must engage with politics and war and “cry over what is happening,” he tells us, in Reiss’s film, for “despair and reason live in the same house.” He did environmental work through the Sierra Club while same offering a grounded literary mysticism, connected to snow and dust as elements of his childhood, as words known in the body.

His first prose book Iron John was an early attempt to give meaning to the male search for something intrinsically and instinctually male that wasn’t wrong, but that needed some skill in mastering. Unfortunately, the book was much misunderstood: the media panned it and perhaps some male seekers took the pursuit of the ‘Wild Man’ too literally. It wasn’t a great book – not a patch on his poetry for passion and subtlety. As the Devon-based storyteller, Martin Shaw said, Bly “has reintroduced the notion that language is wealth.”

But he didn’t pull it off in Iron John, which failed to do justice to his vision. It was panned in Britain at its release.

Hayden Reiss, who made the stunning biographic movie A Thousand Years of Joy[5] on Bly, quipped in an email to me:

“The unfortunate review of Iron John was by Martin Amis: a man with no father issues!”

I much preferred Bly’s second book, The Sibling Society, a powerful critique of post-modern America, and incredibly relevant now when the deconstruction of power and the signalling of virtue have become virtually meaningless. Perhaps “too hard a slap in the face of an increasingly self-absorbed, fame-driven, and now tech-enhanced, culture,” suggested Reiss in the same email.

I recommend the book and the crowd-funded documentary on the Minnesota poet and founder of the Mythopoetic Men’s Movement. It warrants more than one viewing. Witness his joy reading Rumi declare the whole universe is dangling on a swing that hangs between conscious and unconscious realms, which is of course where Bly’s own work plays.

Bly demonstrated that poetry – you know, that sombre stuff they forced us to learn at school and that radio poets recite like bishops – was all about feeling! Through his vibrant translations of feeling from around the world, Bly beamed Neruda, Mirabai, Rilke, Machado, Hafez, Kabir, Basho and other masters into one’s personal body. “He gets it at the level of language, he gets it at the level of imagination, “explains the drummer/ storyteller Michelle Meade.

For Bly, translating the great ecstatics was as valuable as his own work, rooted in the spoken tradition of Yeats and his mentor William Stafford. “These poems needed to be released from their cages,” says Coleman Barks, whom Bly encouraged to take on Rumi. Under the Minnesotan’s influence, I rediscovered D.H. Lawrence’s later poetry, mostly omitted from anthologies. Several took my breath away with their subtleties towards love relations, especially the projected field between men and women and the balance between tenderness and violence.

Bly’s work with men can be thought of as a grounded extension of the poetic. Monday’s Guardian pays tribute to him, but typically misses the point by leading with irony – such a British mistake[6].

“In later life, Bly was a leader of the ‘expressive men’s movement’[7], a controversial effort to ‘reconnect’ men with traditional ideas about masculinity.”

Really? Traditional masculinity? Did I miss something? The article can’t avoid sarcasm:

“In 2016, New York magazine described Bly as ‘a media-friendly shaman for a strange, mythopoetic men’s-liberation movement … [a] flowering of men’s self-help workshops and books [that] managed to be both New Age and retrograde’ and which ‘emerged’ genuinely out of feminism or at least claimed an alliance with it.’”

Bly said his work with men was not meant to antagonise women, telling the New York Times in 1996:

“The biggest influence we’ve had is in younger men who are determined to be better fathers than their own fathers were.”[8]

Bly adored to generalise, but though he was never confessional, he also fed from his own story. Once upon a time … in time … then as now, as he might say … a certain Norwegian American farmer liked his drink too much and his foppish intellectual son too little. Over time, the son chose to love the father and celebrate the hunger men have for their fathers, surprising feminists, who first couldn’t believe that being for men meant not being against women.

Perhaps the most important lesson I took from Bly at those men’s conferences in the early 90’s was the habitual men’s anger with their fathers was actually their longing for his presence. For we have had an epidemic of absent fathers in the West in the hundred years that followed the First World War. Bly brilliantly re-framed men’s anger towards the father as hunger for him.

In this, he drew upon the work of the German psychoanalyst Mitscherlich,[9] who said that if a boy does not know who his father is then a ‘hole’ will be created inside him, and because nature abhors a vacuum, into this hole rush ‘demons’, or fantasies. This hole, or absence, is created both by the father being ‘out’ at work; but it can also occur when the father is at home, but emotionally withdrawn.

When I was a boy, my father’s life was a mystery; on his return from the office, he was usually tired and irritable. Behind the paper he was like a god, never to be disturbed. This was the traditional masculinity. But I was still lucky, for when I was at home I did have a father in residence and that was an asset, for he was like a permanent backstop and could be relied on in times of trouble. A resident father is important. Even if he is not overtly supportive, he is someone to struggle with, to come up against – even to get angry with – for a boy has to do most of his psychological identity work in relation to father.

Later on, in groupwork, I discovered that what men missed in their own fathers they might find in other men, and when this absence and longing is mined in facilitated groups such men can get a chance to ‘re-programme’ their inner emptiness. In groupwork, following men’s longing can often lead to resolution.

Finding his father is central to a boy’s necessary identity quest. This has been well expressed by the psychoanalytic theorist R.R. Greenson, who proposes that boys need both to separate from mother and counter-identify with father to establish identity.[10] This essential adventure is trans-cultural; it seems like it’s built into the many myths, like those of the Hero’s Journey that Joseph Campbell introduced. But, of course, this is all old-hat in today’s identity-fluid world.

Bly taught that fathers have particularly important tasks during the teenage years, especially to be what he called an ‘Oedipal Wall’. By this he meant that a father should be like a wall for the youth to come up against, to argue with, to dispute with, in politics and ethics, to exercise his un-integrated but passionate nature. That way the boy will feel himself at a wall of contact. He gets a sense, from that clear contact, of what he himself is made of, in relation to another who cares about him. The father should be not so strong a wall that the boy is smashed when he comes up against it. But he must also not be so soft, or absent, or compliant or permissive that the boy has nothing to push against.

This means that father has to be both physically and emotionally present, good willed, and subtle enough to be able to think beyond the surface meaning of a boy’s behaviour. A father can do excellent developmental work when he allows himself to ‘muck about’ or ‘rough-house’ with his son. In their mock combat the pair enact all the trials of strength they need to, they flex their muscles together, they learn to have boundaries about what hurts and what is appropriate, but above all they get great contact. The boy gets the smell, as it were, of the father embedded in his psyche; this is a major part of his education.

Bly never glossed over his own failings as husband and father, but proposes “A good way to learn something is to start to teach it.” This is psycho-spiritual psychology, to my mind: human love not differentiated from the elemental. Bly was not transcendent in his approach to spirit, but immanent:

Every breath taken in by the man

Who loves, and the woman who loves,

Goes to fill the water tank

Where the spirit-horses drink.[11]

But he was also fiercely unsentimental. “If anyone mentions the Higher Self again I’m walking out,” he bellowed late one evening session at a men’s gathering. Someone did, and Bly walked. Some were shocked, but I loved it, reeling from the over-conceptualising of the Psychosynthesis I had been involved with.

Beat poet Gary Snyder knew he was rooted in the real:

“Robert was very hungry [when] young, spent some times in isolation and spiritual poverty looking for what would feed him.”

Bly was a brother Snyder says, explaining why, even though not associated with the beat poets, his “poetry was married to politics.”

Yes … and to the earth, and to love, and to women and to the woods. I can still hear the thud of drums from inside some hall as we beat away the morning waiting for the man with his weird nasal voice and colourful waistcoat to appear on the dais and read another poem to the ninety men rapt in attention. We weren’t being ‘wild men’, we were being real men, celebrating the ecstatics. What a loss.

The author, Nick Duffell, is a psychotherapist, psychohistorian and menswork facilitator. More about his menswork on www.genderpsychology.com and a new training in facilitating therapeutic men’s groups begins March 2022.

[1] Duffell, N. (2000) The Making of Them: The British Attitude to Children and the Boarding School System, London: Lone Arrow Press.

[2] https://www.theguardian.com/global/booksblog/2016/aug/06/mark-rylance-how-robert-bly-changed-my-life

[3] See ‘Listening to Shahram Nazeri’ in Bly, R. (2013) Stealing Sugar from the Castle: Selected and New Poems, 1950-2013, New York: W. W. Norton & Co.my teeth.”

[4] Bly, R. (2004) My Sentence Was a Thousand Years of Joy, New York: Harper Perennial.

[5] Haydn Reiss’s film on Robert Bly A Thousand Years of Joy http://robertblyfilm.com/ takes its title from the poet’s 2004 anthology, My Sentence Was a Thousand Years of Joy, New York: Harper Perennial.

[6] https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/nov/22/robert-bly-award-winning-american-poet-died-age-94

[7] https://nymag.com/article/2016/06/how-poet-robert-bly-started-the-drum-thumping-mens-movement-of-the-90s.html

[8] https://www.nytimes.com/1996/05/16/garden/at-home-away-from-home-with-robert-bly-now-banging-the-drum-slowly.html

[9] Mitscherlich, A. (1969) Society Without the Father, London: Tavistock.

[10] Greenson, R.R., ‘Dis-identifying from Mother: its special importance for the Boy’, in International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 49, 370, 1968.

[11] Bly, R. (1985) Loving a Woman in Two Worlds, New York: Dial/Doubleday.

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.