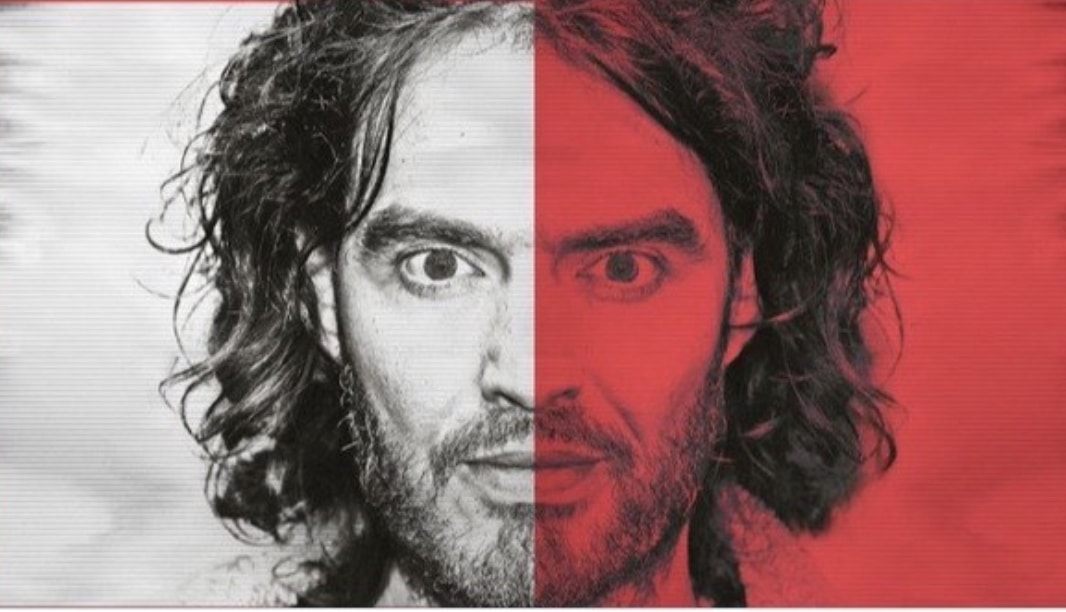

Russell Brand and the kitsch creep persona

Masculinity

Russell Brand has been accused of criminal behaviour on Dispatches, but why was his extreme behaviour, which led to the allegations, enabled?

After the allegations of rape and sexual abuse and coercion that were revealed in the Channel 4 Dispatches programme, ‘Russell Brand – in plain sight’, there are many questions to now be resolved, first and foremost around a possible prosecution. Whether the show and the article in the Sunday Times will result in a police investigation, or if we can expect Brand to respond with a defamation lawsuit – possibly both – this is sure to be a story which will become legally protracted and played out across media channels for some time.

Yet other questions must be asked by all of us, around how Brand managed to operate for so many years at such promiscuous extremes. Which is not to say that promiscuity is a crime, merely that such extreme promiscuity, where, as he wrote in one of his books, he had “a harem of ten women, whom I would rotate in addition to one-night stands and random casual encounters,” cannot possibly be all sweetness and light. All the thousands of encounters he had may have been consensual – though, not according to the women in the programme – but was it a case, as Brand put it, that they were women “who have the same disregard for the social conventions of sexual protocol as I do.”? Perhaps there was a meeting of minds in many cases, but surely power and fame are the key elements here, not social iconoclasm. As Brand himself put it: “It’s the scale of my sexual endeavours that causes the problems, not the nature of them….I’m a bloke from Grays with a good job and a terrific haircut who’s been given a Wonka ticket to a lovely sex factory ‘cos of the ol’ fame.” Well, indeed. The problem is, given that extreme scale, were all his partners, every single one, having a great time at the lovely sex factory too? If he does have a sex addiction, as he claims and has been treated for, the act is the priority not the person, as it would be with any drug. The buzz is the thing.

Therefore there is necessarily an element of degradation here for the women involved – as the buzz is thing, from whatever source is available. This must have been recognised within his social circles, at his workplaces, among his employers and friends, and in the media. His was a very public performance of compulsive sexual behaviour. And it was accepted. Even became the key thing he was celebrated for, whether it be in The Sun where he was Shagger of the Year three years in a row, or the way it became a cornerstone of his stand-up and his books.

It was accepted because of the layers of camp he added to his persona, the laddy humour, the larking about that gave his behaviour a fun veneer; like, it wasn’t serious, so what’s the problem? It’s just a bit of sex. Except sex is not simply an act. It involves another person. We know this and can see how being used for the buzz could be really quite unpleasant.

The acceptance of his behaviour wasn’t just about power and fame, it was also linked to the persona he created – that of the grotesque.

At one point in the documentary, they play an interview he did with Jimmy Saville on his BBC radio show and Brand jokes about sending his assistant over naked to Saville. Brand didn’t know he was speaking to one of Britain’s worst paedophiles at the time, yet there is an uncomfortable chumminess between the two around this pervy chat. Saville had also transformed himself into a grotesque to achieve fame, TV appearances. You couldn’t like Saville, even when his acts weren’t known, but he was a character, a larger than life figure And Britain tends to allow grotesques to flourish in public life, those fascinating weirdos who demand, and receive, attention. Not all of them are predators of course, but for Saville, his bizarrely creepy act acted as a smokescreen for his behaviour. Surely even the dark mutterings about him throughout his career couldn’t be true, he was just a harmless eccentric, right?

For Brand, his outrageous persona enabled his behaviour rather than disguised it. As he mentioned in his post about Dispatches in which he refuted the criminal claims and stressed he has been “transparent, too transparent” about his sexual behaviour – but this very transparency was a ready-made excuse for it. After all, since he was so open about his sexual compulsiveness, what could any woman expect other than to simply be another notch on the bedpost.

Brand’s was a kitsch creepiness. A near-parody of a permanently randy, womanising Englishman. With the emphasis on near-, because despite the layer of effete verbosity and peacocking charm, underneath it he really was a permanently randy, womanising Englishman. Dress it up all you like, as social anarchy, playful naughtiness, seaside postcard rudeness, he was shagging everyone he could, and was absolutely on the hunt, at all times. This is not criminal of course, but in operating at these extremes, under the veil of irony, it is easy to see how it could potentially become so – with the women in the programme talking about coercion, pressure, doing things against their will. And, even if the allegations turn out not to be true, it is clear his behaviour really is (or used to be, if he has changed his ways as he claims) all about his will. Which was to have his fill in the Wonka factory.

A man who was allowed to have his fill too. For the other factor here, is that his behaviour also fulfilled a typical male fantasy. The rake who can have his way with anyone. It’s been a popular idea since Casanova, and lived out by the likes of Errol Flynn and Mick Jagger through the years. Pop psychology will have it that this is evolution at work, with males hardwired to want to impregnate as many of their tribe, and every other tribe, as possible. While evidence has painted a different picture of male faithfulness and female promiscuity, such ideas of ‘sowing wild oats’ remain in society.

And until we change such ideals, through discourse at home, in schools, in workplaces and friendship groups, this idea of male success via your ‘body count’ is one which not only creates false goals for happiness, but allows the extreme behaviour of public figures like Brand to be accepted – until finally a woman speaks out. In this, then, we are all not implicated as such, but all have a role to play in changing the type of behaviour that is valued. That doesn’t mean some joyless asexual puritanism, it simply means creating a situation where numbers matter less than connection, when the compulsiveness of sexuality is outgrown into more respectful and responsible approaches. The world is not a chocolate factory on which to gorge, it is a place shared with other humans.

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.