15 way to rethink masculinity from a trans boxer

Masculinity

An interview with writer Thomas Page McBee about boxing at Madison Square Gardens and what we can all learn about trans, toxic masculinity and becoming a better man.

‘Amateur’ is one of the books that seems to clear all the smoke from your eyes to reveal the world as it truly is. New York journalist Thomas Page McBee first came to attention over here with the story of his transition in ‘Man Alive’, but as we find out in ‘Amateur’, his journey was far from over. After finding himself getting involved in street fights he decided to explore the violence of men by taking on the challenge of a charity boxing match at Madison Square Gardens. In the process of the training, Thomas asks himself hard questions like ‘Why do men fight?’ and ‘Am I sexist?’ as he explores not just socialised, and toxic, masculinities but the whole system of gender and power.

We spoke to him in London at a pirate-themed café – don’t ask – and are extremely pleased to present you with extended highlights of a revelatory exploration of the most important issues hitting men today, by one of today’s most important writers.

1. We have to talk about masculinity

I transitioned in 2011, two years after the recession, at the beginning of what was widely being called the masculinity crisis on a global scale. I was reporting on that, writing stories about men who are out of work or killing themselves at higher rates, and then at the same time experiencing my own socialisation as a man of my own in the world, which was echoing some of the themes.

What I mean by that is I’d be happy in my house, just in my own body, it was great, but when I’d leave my own apartment, I was experiencing, firstly, privileges. Which included privileges at work: when I spoke people would now listen! I’d get to silence a room with my mouth, and I was never interrupted. I was getting raises more frequently, progressing in my career. And I was able to walk along on the street at night without any fear at all – but instead I became a threat to women, which was upsetting. Women would cross the street to avoid being near me if it was a dark night.

So there was the privileges aspect and the constrictions aspect. I was very aware that overnight I suddenly was being touched a lot less and being expected to be strong in a certain way and not show emotion in a certain way. All of that came to a head in 2014 because my mum passed away. I was having grief, which is not something you have a lot of control over, and I had this summer where every single month I got into these street altercations with these guys who wanted to fight me. I never started them, but I found myself in these moments where a man in New York would pick me out for whatever reason. I think it was because probably I was giving off a vibe of anger, I was so upset, in grief, and I didn’t know how to express it.

In August of that year, the last straw was this really prolonged altercation with this dude – it didn’t come to blows but it almost did. And it was very silly, it made no sense – it was about taking pictures of his car, which I didn’t do – but for me that was the turning point where I realised if I didn’t handle this differently I was going to just become formed by the world that was expecting me to behave a certain way, because I was seeing in myself those behaviours.

After I got out of the almost fight I had a question in my mind: “Why do men fight?” And I know with masculinity, it’s like Fight Club, you’re not supposed to talk about masculinity, but it seemed the only way to be in alignment with my values, was to start asking questions. So that’s how I ended up getting involved in fighting at Madison Square Gardens, because one thing just led to another.

2. Destroy the macho, embrace vulnerability

In the beginning of my training, my signalling of masculinity – what my wife called my romantic masculinity – was in full swing. Most men walking into an environment like that think ‘I can do this, I can keep up with this.’ On a surface level I had that at the start, but it had only a tiny relationship because I was bad at the boxing. And it was stressful because I had to fight in Madison Square Gardens with only 5 months to train. Sure it looked cool and my work colleagues were impressed but I still needed to figure out how to do this. It was really hard.

Everything turned when I really committed to it as a sport and understood it – I realised it’s a sport that’s really about vulnerability, because you are never more exposed. I will never be more exposed in my entire life than when I was sparring or fighting. Anybody looking can see what you’re scared of, what you do when you’re pressured, how you handle being knocked down…which express deep down all of those things you are as a person. I realised under the cover of violence, everyone around me was having that experience, and those men were very much more capable to be intimate and to communicate, and to have empathy. Because the whole job was to help people get better; there wasn’t any policing of masculinity because there was no need to. With that removed it created a real communal sense of seeing how you can get better at this thing you’re struggling with and turn it into a strength. Because, you can’t hide it, it’s not a team sport.

I’d never talked to anyone more about how much I’m eating, how much I’m sleeping, what spiritual crises I’m going through, what is going on in my relationship – all of that mattered because it affected how you were performing in any given day. It really was a surprisingly intimate experience to be training along with other men.

3. Identify Toxic Masculinity

The consensual fighting of boxing was a completely different kind of fighting than the guy on the street who has the markers of what sociologists call ‘toxic masculinity’. And just to define it, that’s not masculinity broadly, that’s not an adjective for masculinity, it’s a socialised set of behaviours that we teach boys about what it means to be a man.

That’s best illustrated by the idea of the Man Box. If you ask boys what a man means they can tell you: “Men are strong,” and “Men don’t cry,” and they put all these descriptors in this box, with the idea that it’s very constricting. And then if you ask those same boys, “think about a man in your life that you love, your dad or your coach, how does he behave that doesn’t fit into this box?” And they always have a whole list of behaviours that are considered ‘feminine’, so they can see what I’m supposed to do and what I actually appreciate, is very different.

I think the reason why men start street fights is that a big part of that aspect of toxic masculinity is domination and proving your own masculinity through dominating. It’s because of this idea that there are ‘real men’, and there are men who are therefore not real. Part of masculinity is guarding that realness, so when you feel your masculinity is threatened, you feel the need to act out in some way to reaffirm your masculinity, even if just to yourself.

The idea that you would not feel like something you are, I think, it’s the most depressing thing, and actually because I’m trans, I’m shocked that so many men who aren’t trans are experiencing that on a daily basis.

4. Question how we socialise boys, and question yourself

I did the boxing and every question that came up for me, I really committed to reporting out the answer. Like ‘Does testosterone make us violent?’ Or ‘Am I sexist?’

Almost every historian, every sociologist, every development psychologist, pointed me back to boyhood. How we socialise boys is crucial – boys have no ability to consent to the socialisation, they don’t have frontal lobes, they can’t even think about what they’re learning – but we socialise boys to think a certain way about what being a man is. And that’s proven, there’s plenty of evidence that’s true. You’re calcified an identity. Then they grow up and behave in those ways, and we hold them accountable without any dialogue about how this came to be – it’s very hard to hear someone tell you you’re doing this wrong without a sense of it’s purely your personal failing.

That’s where the good man, bad man thing is a really pointless framing. Because for there to be good men there has to be bad men. You’re either good, which everyone wants to be, but there’s no agency or self-examination in that, or you’re bad, which is upsetting.

The psychologist Niobe Way had a great reframing of that question, which is instead of saying, ‘Am I good man?’ ask yourself, ‘How am I maintaining the status quo?’

It’s just a way of being part of the solution and including your own self-enquiry as part of that solution, instead of making it something where you’re organically either above it all and not having to participate in conversation, or bad. There’s very little on that scale about being human.

5. Seek to change Alpha thinking at work

Work and inter-personal relationships are places men can effect real change. Early on in the book I have this experience where I’ve been training for a month, and have to spar with a woman. Normally you never spar with a woman if you’re a male boxer, but I was co-training with this woman who was also training for this charity night, and she had been training for a year. And she was really good. My coach wanted me to actually spar her, not pay defence as you normally would. She was a high-powered attorney and into it but I found myself resisting. In part because I didn’t want to hit a woman – that had been drilled into me – but also because I was embarrassed: I didn’t want men to see me spar with her. And that really brought up this question of ‘Am I sexist?’ Is that possible? Can I be a person who had this life experience and be a feminist, and then be sexist?

I really had to answer that in a deep way, and work was a good way to answer that because I had to look at my behaviour. I kept track and noticed that I interrupt women more than I interrupt men, I speak over women more, I answer men’s emails more quickly. And once I had that data I was able to rethink how I was acting at work. What I found was just doing the opposite was a way to undo it. So for example, men never ask for help, so I asked for it, especially from the women around me. ‘Can you give me some feedback on me at work?’ ‘What can I work on to be better?’

Actually it was really great, people were willing to engage and come up with solutions, which were things like listening, or making space for other people to speak first, or being a better ally. If I was in a big meeting and women were not being listened to in this unconscious way, I’d could say, “Oh you know Jane said earlier that same thing” and try to be part of the glue that holds us together and makes us more of a team.

6. If you’re worried you might be a toxic guy…

You probably are! But that’s not because you are failing, it’s not because you have failed to become a good man, it’s because you live in a culture in which you have been taught to behave in a way that you have internalised. The solution isn’t to be like ‘oh no I’m a bad person’, or ‘no way I never learned that’, because you would be the one person who’s escaped socialisation! It’s more about understanding the system and seeing where you are with these things, and then you can change it.

7. Think about how patriarchy affects you

If you are in power, there’s a collective system which keeps you in power, unconsciously, which is fundamentally about being better than other people, and therefore deserving to be in power, and that’s what patriarchy is.

I think we need to get away from the idea that just because some people are in power doesn’t mean they’re having a better experience of being a human being. The way men have been taught to think about patriarchy is that’s a word about feminism and about something that’s a threat to me, and they don’t want to hear it or think about it.

I was thinking a lot about the constriction feeling of being a man and what I was expected to do in my body, and it wasn’t that I looked at all this and now I’m some failing person – that I’m a total disaster because I haven’t really embraced patriarchy in this particular way. In fact, the opposite’s happened, the more honest I’ve been with myself and put these ideas in the world, the more I’ve been literally rewarded for thinking differently.

I think that the rub is that we are scared because we think this is the only way to live. And it’s unconscious because this is how the power has come to be and we consolidate power this way and we benefit from it, but I think we never talk about the drawbacks of it. For men, not just for everyone else, but for men. And they are numerous.

8. Rethink the hunt for power

It’s a lie because only a few people get it – only 1% of the people own 50% of the wealth – there’s never going to be a time when all of these people fighting so hard to have power are going to have it.

People say it’s innate behaviour, but it’s not. I aked the neuroscientist Robert Sapolsky from Stanford: ‘Does testosterone makes us aggressive?’ And his answer was ‘No, that’s the biggest myth there is about testosterone. There’s no aggression receptor in the brain, that’s not a thing – but it does make men status seeking.’

They’ve done economic games where in order to win the game you have to be cooperative, and in those games the men with the highest testosterone levels are the most cooperative. But if you give men a placebo, and tell them it’s testosterone, those men will act like total assholes in those same games. Obviously this is the nurture idea that we tell ourselves is the nature idea. It justifies this endless cycle which doesn’t benefit us, because most of us are not coming out the winning end of it actually.

Of course power is much more organised around men than women, and white men in particular, but I don’t think a reimagining of that is about stripping people of power, it’s about reconceiving how we even think about power in our culture.

9. Don’t concern yourself with being a ‘real man’

My understanding of identity theory, psychologically, is that people are most likely to identify with that particular identity if that identity feels threatened. So built into toxic masculinity is masculinity threat. If you ever want a man to act like a man, tell him he’s not a man, and then he’ll act like a ‘real man.’

Real men have got to be in the man box. ‘Somebody is telling me that I’m not a real man or being a real man isn’t a worthy endeavour so now I’m threatened and I need to prove I am’. They’re stuck in this cyclical thing.

What I make of the online ‘manosphere’ is that it’s dangerous. I think that level of rhetoric and total refusal to engage with ideas beyond it is reprehensible, morally.

Though I have a lot of empathy for men who are grappling with those issues and don’t know where to start, once you have access to information that can help you fix some of these things and you refuse it, I think you’re morally accountable at that point. That’s a choice you’re making.

10. Don’t be paralysed in this discussion

The most dangerous people are the violent people, but what’s also worrying is all the men in the middle who are not being accessed or who are struggling to figure out a way to think about this. I always forget the Martin Luther King quote about the white moderate, who will stand by because they don’t want to be uncomfortable.

[This is the MLK quote:

I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice]

But then there’s the other issue of men not knowing what to do.

Rightly, there’s been a lot of anger from women and people of colour and trans people and people of sexual minorities, feeling very frustrated with this totalitarian moment that we’re all in. That anger is important and it needs to be expressed. For a lot of men, the feeling can be ‘Ok I get that people are angry and I don’t know what to do.’ And ‘But I’m not a bad guy’. Because that’s what we’re taught to think. I think just trying to break out of that cycle.

I had to think about this at 30 so I had a huge advantage because I had an adult brain with which to consider it. Most men I’ve spoken to had a story about their own boyhood when they started to feel things were fucked up, ‘why is this happening?’ If men can get back in touch with their own internal sense of dissonance, about ‘who I am’ versus ‘how am I expected to behave?’, I think that’s the way, literally, towards liberation.

If you’re the kind of person who cares about being independent in the world, and being an independent thinker, and not being hemmed in by cultural restrictions in general, it should appeal to you. The idea of getting out from under this completely false sense of how you’re supposed to be, because you’re not liberated in yourself if that’s how your life is playing out.

11. Understand Transitioning

In the media the trans narrative very much ends with the transitioning, for better and worse. In the best case it’s about this authenticity, of finally becoming yourself, which is very appealing, everyone loves that idea of finally becoming yourself. You did it!

But like any transition, it’s a process.

I thought I’ll transition and then I’ll feel better and that will be that. I didn’t think about what that would mean past that point, what it would be like to be in the world, and how that might feel, so I was pretty shocked. I was only excited about the clothes I would fit into and how I would feel about my body and all those things were true.

I think one of the great paradoxes of my life is on one hand I know gender is constructed, I know that in many ways we are creating ideas of what gender means all the time – and on the other hand I am transgender and I have experienced dysphoria in my body and that was very real and I had to do something about it.

Where I hold that paradox is just thinking about it in the sense of, yes, there’s something innate to me about gender, or sex generally, but not about the way in which we decided together to make it be!

My actual transition was great, I felt a lot better about myself physically, but the focus on the physical is so boring to me. What was really a challenge was what came next. In identity formation the first step is becoming yourself, and then the second step is finding your place in the world. And I think that second step totally knocked me on my ass, I had no idea what that was going to be like.

12. Understand the freedom you have as a man

After my transition, it’s a gross word but it felt like I had a lubricated experience of the world, because I’m also white. Before I had an androgynous gender identity which is probably one of the more maligned ways to be walking through the world. I didn’t really make sense to people, except for a very certain subset. Even though I had a professional job I felt people who weren’t in my world didn’t know what to do with me. Then suddenly, within months, I’d be rolling through the toll booth and have someone be like, “hey brother!” That was so odd for me. And upsetting I guess – “Why should I have this? Why can’t everyone treat everyone this way?”

There’s an Eddie Murphy skit for Saturday Night Live, where he put on white face so he can walk around New York as a white man, and he gets everything for free, and as soon as the one black person leaves the bus, there’s a party! But it kind of did feel like that to me. The level of privilege is unbelievable.

I don’t want to downplay how big of a choice it was for me, and a scary one. To inject testosterone, hich not all trans people do, but for me to inject hormones, I didn’t know what the health outcomes would be, I spent a lot of time worrying about ‘will this affect my ability to get housing?’ ‘will this affect my ability to get a job?’

But now I see how lucky I am that I have the privilege of passing in the world. Because that is where all those privileges come from, it’s not from being trans, obviously, it’s from people not knowing I’m trans.

13. Find new role models

I think it does disservice to trans people for it to be framed as a neat and tidy arc where you transition and then it’s over, whereas it’s the opposite of that actually. That was hard, but now it’s harder. ‘How do I figure out how to live by my whole values of my whole history, and have a meaningful life that hopefully goes on a long time?’ Firstly I have no role models of people who have lived through my experience for very long, and also as a man, separate to my trans experience, I don’t see a lot of role models either, with a certain type of masculinity. At least in older people. I’m very excited by younger people, because I think younger people are rethinking all these things in a really exciting way.

14. Beware of bystander effect

The bystander effect when it comes to other men’s behaviour is damaging, the inability to speak and to say something. And that goes back to ‘Don’t ever question masculinity’, ‘Don’t ever question power’, ‘Don’t ever question the system’.

If you even buy into the good qualities that we affiliate with masculinity, like being brave, that’s not about sitting in silence while someone does something terrible to someone else.

For me being brave is speaking truth to power.

15. Box!

It’s hard to hit someone, the hardest part. I was a keeper in soccer in high school and I’m very comfortable with taking hits. That part wasn’t so scary but it was challenging to hit someone. You can’t fight angry because it makes you stupid.

I think in the fight itself I had to summon up enough feelings in a controlled way of something like anger to hit that hard. You need enough emotional energy, which is the point of the pre-fight talk – to wind people up to the point where they can actually fight.

In sparring you’re not trying to take someone’s head off, you’re trying to learn and get better. You can get hurt but it’s like you’re operating at 25% so I think with sparring it was about realising I was in a consensual dynamic. I learned a lot from the men around me who made it fun, so I didn’t feel like I was hitting someone in order to hurt them, but in order to get better at a sport.

The actual fight was more of a challenge because I wasn’t mad at this guy but we had to hit each other like we really wanted to do serious damage, because that’s the point of the sport. And that was really hard, I had to dig deep.

The whole thing is about confronting your shadow, so when you know you have it in you to do that, I think it’s an important thing. We all imagine what would happen if someone attacked us. It’s kind of good to know that you can fight for your life, if you have to.

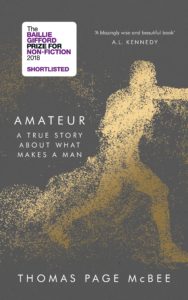

Amateur by Thomas Page McBee

The story of the first trans man to fight at Madison Square Gardens, and a journey into what really makes a man.

www.amazon.co.ukTrending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.