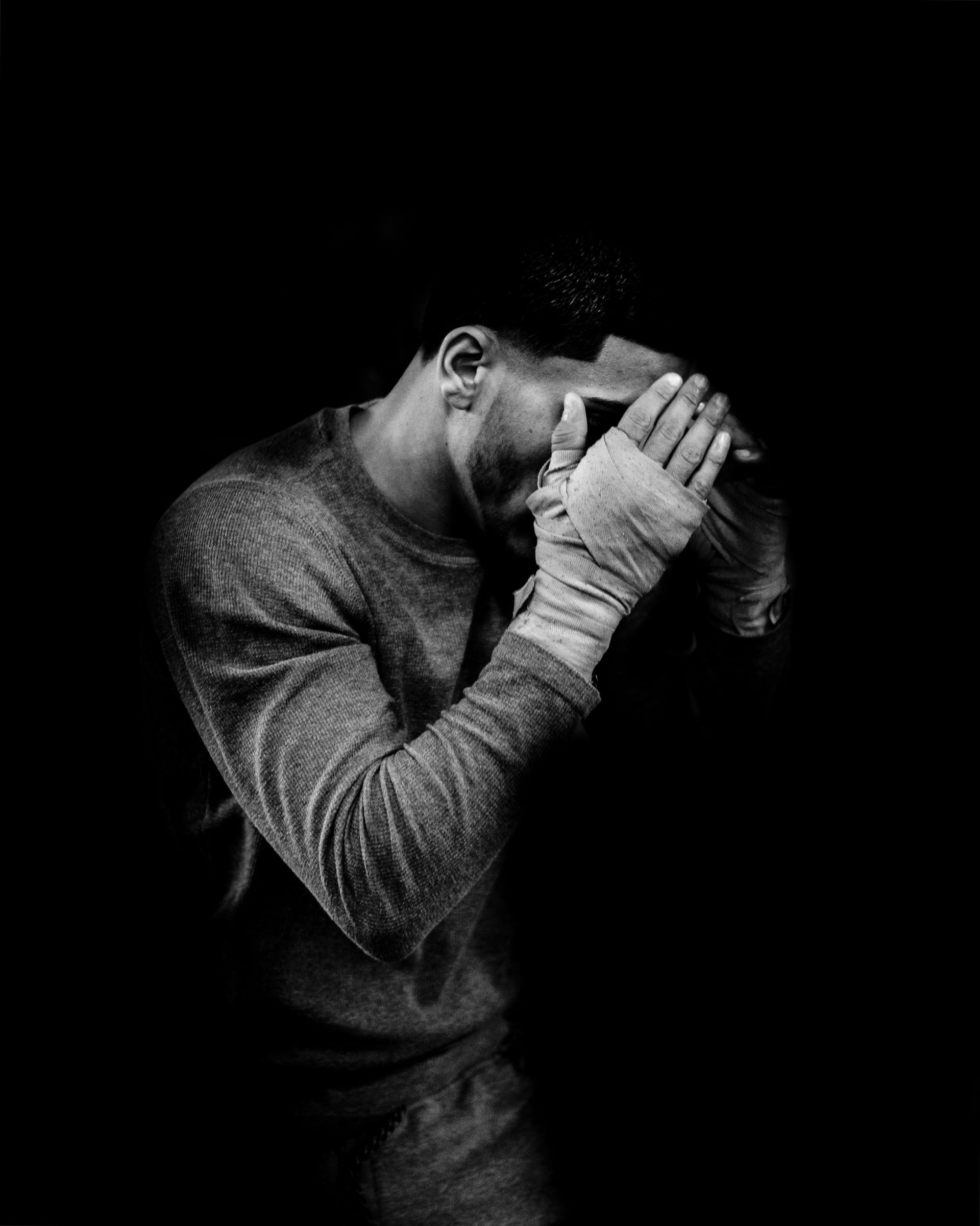

Black men’s mental health: why the stigma must end

Mental Health

Sagal Mohammad on the damaging idea that "black people don't go to therapy" and the role of young black men in changing attitudes to mental health.

“Black people don’t go to therapy,” is the song that has been sung within African and Caribbean communities across generations. For men, it’s echoed and put on repeat. So much so that suffering in silence has become their go-to method for dealing with common mental health disorders.

The statistics

Last year, a Race Disparity Audit published by the government highlighted that Black men were more than 10 times more likely to have experienced a psychotic disorder within a year than white men. Yet it also showed that Black adults in the UK as a whole were the least likely to report being in receipt of any treatment, medication, counselling or therapy. They were also the most likely to be detained under the Mental Health Act. But where exactly did the stigma around seeking help for mental health issues come from? And more importantly, will it ever not be a taboo?

Lack of trust

A huge factor in this is the lack of trust in services. According to mentalhealth.org, Black and ethnic minority groups living in the UK are more likely to experience a poor outcome from treatments – a fact Councillor Jaqui Dyer, vice-chair of England’s Mental Health Taskforce and co-founder of Black Thrive (a community-led initiative to create a more positive story around mental health in the African-Caribbean community) says has a lot to do with the lack of cultural understanding between a psychiatrist (who is often white British) and an ethnic minority patient. “You’ve got the same players making the same decisions about people that they know nothing about. They are designing services and improving services but at a distance,” she said in an interview with Channel 4 News. This often results in cases of overdiagnosis which in 22-year-old Miles Johnson’s case, has lead to a complete loss of faith in mental health services.

Miles

At the age of 16, Miles, who is of Caribbean descent, was almost sectioned after reluctantly agreeing to talk to a psychiatrist about his depression; something which stemmed from growing up in a rough Hackney neighbourhood where gang culture, violence and drugs were the norm. “When I went to see the psychiatrist, I wasn’t talking about self-harm or anything like that,” he tells me.”I was just opening up about where I come from, what happens there, and how I felt about that. Yet in their eyes, that meant I was a danger.” Due to his age and the fact that he was months away from finishing college, Miles was given permission to leave the session, however, that remains the first and last time he spoke to professionals about his mental health. “As Black men, we are viewed as intimidating full stop,” he says. “And as long as that exists in our society, people will always be quick to fear us. Add a mental health disorder to that and we’re even more terrifying – how are you supposed to give someone the help they need if you’re scared of them?”

Eche

Last summer, Eche Egbuonu, a Black British man who lives with bipolar disorder, made headlines for calling out the ‘institutional racism’ within the UK’s mental health services. His claims came after he was sectioned under the Mental Health Act and thrown into a prison cell instead of being taken to a hospital or another safe environment. The story broke at the same time as the BBC reported that research by the think tank found that ‘when black people tried to access help, they were less likely to receive the support they wanted.’ Experiences like these continue to fuel the overriding narrative of mental health hospitals being a place of ‘doom’ and ‘death’ within African and Caribbean communities, and have caused many young men and their families to either suppress their feelings or look to religion for help.

The traditions

As a teenager, I watched my father, a Somali-Muslim, suffer with severe depression and paranoia after going through some tough life changes. For years, his mental health was the elephant in the room at family gatherings as he lived in denial. It wasn’t until my grandmother begged him that he agreed to seek help the “traditional way” via religion. We visited an Imam (the Muslim equivalent to a priest) who performed a special prayer on him and our family to rid us all of the “shaitan” (devil) inside him. I remember thinking how stupid the whole thing seemed, especially since my parents are far from traditional both culturally and in religion. They are, as my grandmother would say, “westernized in every way” having spent the majority of their lives in Europe. Yet this was one problem they felt needed to be dealt with the way it would be “back home” in Somalia. Not to my surprise, the Imam’s prayers didn’t turn out to be the magic cure my grandmother had hoped for. Instead, depression has become just another part of life for my father – one he has learnt to overcome in his own way, with only my mum and I as his “therapists.”

Masculinity

While I don’t necessarily agree with my father’s choice not to seek professional help, I can understand why. On top of dealing with the thought of being misunderstood and mistreated by mental health services, Black men have another major factor to consider before asking for help: their masculinity. Men in general have historically been forced to adhere to standards of toxic masculinity, with expectations to ‘suck it up and move on’ whenever experiencing any emotional trauma. For black men, this is intensified due to not only the expectations set for them by society to be “strong” and “fearless”, but the thick skin they’ve had to grow in order to deal with the unconscious bias and racism they endure on a daily basis; a prime example being the Starbucks incident in Philadelphia where two Black men were arrested for simply asking to use the toilets.

Daniel

Daniel Smith, a 20-year-old British-Ghanian from Strafford struggled with depression for three years and didn’t tell a soul due to fears of being labelled weak. “Where I’m from, talking about your feelings is a sign of weakness,” he says. “Things like depression and anxiety aren’t even acknowledged in a lot of African households so I didn’t feel comfortable bringing it up, especially as a man.” One thing that helps Daniel, and many other young men like him, is the rise in mental health discussions among Black men in the media – more specifically, watching his favourite musicians talk openly about their own battles with mental health. “When Stormzy opened up about his depression last year, I thought that was really powerful,” he says. “For a grime artist to do that is a big deal and I thank him for it because so many of us can relate.”

The rappers

Stormzy is one of many Black artists who have been vocal about their struggles with depression in recent years. Last year, Chance The Rapper opened up about his experiences with anxiety during an interview with Complex, while Kid Cudi shocked fans in 2016 after revealing that he had checked himself into rehab due to suicidal thoughts and depression via an emotionally candid Facebook post

Hip Hop

The Hip Hop scene as a whole has become more open to discussion around mental health, especially with the rise of emo rap; a subgenre fusing trap and hip-hop style beats with the dark confessional lyrics often heard in emo music. New gen artists such as late rapper Lil Peep, XXXTentacion, Trippie Redd and Lil Uzi Vert, who received a Grammy nomination this year for Best New Artist following his 2017 club hit ‘XO Tour Life’ (a song about dying relationships in which the chorus goes “push me to the edge/all my friends are dead”), have shot to fame for their ability to get real about issues that have traditionally been ignored in their communities, and hopefully, they’re encouraging a new generation of young men to do the same.

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.