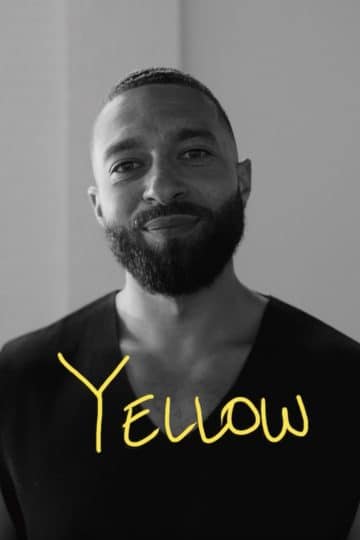

Living With PTSD: Adapt & Overcome

Mental Health

Paul Fjelrad on why the toughest lesson he had to learn during therapy was about accepting his future, not his past.

Amongst the many misconceptions about PTSD, and the treatment survivors go through as they heal, the most difficult for people to accept is the realities of recovery from psychological trauma. When I’ve spoken openly about my trauma and therapy, remarkably it’s often not the darkest aspects of the abuse I endured as a child, or the damage I inflicted upon myself as an adult, that makes them the most uncomfortable. So, let’s tackle some of these misconceptions, and why these seem to make people so uncomfortable when I talk about them.

Firstly, despite what we may want to believe, therapy does not erase a single traumatic memory, and for horrors such as abuse, it’s unrealistic to expect these memories not to continue to be painful, and they will often remain as triggers for someone with PTSD. If a survivor doesn’t want to talk about those memories, wants to avoid a particular place, reacts badly when you sneak up behind them, or even still doesn’t like Christmas because of associations with their trauma, it’s not for you to judge.

Secondly, despite our societal obsession with forgiveness, it is not the only path to healing. It’s OK to still be angry at those who hurt you, or the situation that resulted in you being hurt. This can be the path for some, and I will celebrate anything that helps a trauma survivor to rebuild their life, but if I say I’m still angry with my abuser, and that trying to forgive them would cause me more psychological harm, than good, this does not mean I’m still ill. If I have learnt anything from my own experiences, research and the many conversations I’ve had with those who have struggled with their mental health, it’s that there is not one path that fits all.

The biggest misconception, and the most challenging for both the survivor and those around them, is the idea of being cured. Embodied by a question that I know and hate, “So, are you all better now?” PTSD specifically brings a whole new challenge to recovery, in the form of pre-trauma identity. In most cases, there is a clear identity as the person you were before the traumatic events. This identity can feel like an anchor, so you can work your way back to the person you knew, or it can be a source of pain, as you struggle to understand why you’ve changed so much, and can no longer do what you used to be able to do. With the right therapy and support around you, the aim is, of course, as with any injury, to get you back to as close as possible to the person you remember, with all that entails. This unfortunately isn’t always possible.

While the debate continues about genetic risk factors, and whether you can develop resilience to trauma, I’m not alone in seeing PTSD as an injury, not an illness. While sometimes you can recover completely from an injury, and have it not change you in any significant way once you have healed, injuries can leave scars, and often leave you with a legacy of restrictions you need to adapt to, and learn to overcome.

The physical damage from a severe car accident could leave you with restricted movement, residual pain, or scars you hide so you aren’t constantly reminded of no longer being who you were. It can be the same with psychological injuries.

Trauma changes you. It can re-shape who you are, transform your priorities in life, alter your beliefs, and change what you are capable of, but it doesn’t and shouldn’t define you.

Complex PTSD, differs because rather than being due to a single traumatic event or period in your life, it is caused by multiple traumatic experiences throughout your life, frequently layered on top of childhood abuse, neglect and trauma. In the most severe cases that started in very early life, it can mean that you have no pre-trauma identity.

This is how it is for me. I have often said that trauma raised me. When I was first told about PTSD, the psychiatrist directed me to the website Out Of The Fog (https://outofthefog.website/cptsd), which has many resources and definitions, which were invaluable for someone like me, trying to understand a new diagnosis.

Reading the list of PTSD symptoms for the first time, it felt like I was reading my personality profile. I even liked some of those things about myself. But this led to an existential crisis, that many who have been battling PTSD for a long time have faced.

Who am I if you take this away?

It really can feel like you are now the literal personification of an illness. Accepting how trauma has changed you, can mean accepting living with some PTSD symptoms, for either many years or even the rest of your life. After 3.5 years of intensive treatment, and 5 years learning to live with the new me, I’ve had to accept I am carrying a lot of scars. I regularly get floored with migraines. I still wake up, more or less every morning, with pain. I still have night-terrors, albeit more infrequently as time goes by. Due to this and decades of sleep disturbances and anxiety, I suffer badly with my teeth, which have been ground down so much I am looking into whole mouth dental implants.

I still have bad days. There are mornings when I wonder whether I’m going to get out of the door today, and days when I don’t make it. Days when I am overwhelmed, withdraw into myself and old feelings resurface that make me feel like I’m going to lose this fight. But I haven’t lost yet and over time I have grown more sure in myself that, even when I’m in those dark places, it will pass.

The last time I had a bad bout of symptoms, particularly the insomnia, pain, and night-terrors, was 2 weeks ago, and 9 months before that. It seems so hard for others to accept that this is what good looks like for me, and actually shows things are continuing to get better. How uncomfortable this makes people, certainly doesn’t make it easier for me to talk openly about my mental health.

During the workshops I run on mental health support in the workplace, I sometimes use this story about my mother. She had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis 10 years earlier, and one morning she returned from the GP’s surgery and said,

“No-one ever tells you about the positive side of MS”. Knowing my mother’s sense of humour, I waited for the punch-line. “Did you know that when you MS you can longer get sick with anything else? Whether it’s a cold, back pain, a stiff elbow, or nausea, it’s all the MS.”

She meant, of course, that all anyone ever saw when they looked at her, including her GP, was the MS. She had stopped being a person, and become the illness.

I hope you understand that I can’t tell you how to stop being uncomfortable around this challenging subject, aside from to be willing to talk about it, despite your discomfort. As is often the case in my workshops, you may now be asking how you should talk about mental health with someone who is struggling. My answer is to share the advice given by a sailing charity I have worked with, because the 4 simple rules, are simple, direct, and easy to follow;

- LISTEN, don’t ASK – leave space for them to talk, but don’t dig or interrogate.

- OFFER, don’t TELL – let them know that help is there, but don’t try to force it.

- NO, you don’t understand – regardless of your own experiences, you aren’t them.

- DON’T try to solve the problem – just support them, particularly to get the professional help they need.

But also recognise that someone with clinical depression, can also just be sad. Or laughing, joking, and being the life and soul of the party. Someone with anxiety can just be justifiably scared or nervous about something. Someone with PTSD, can be angry or calm, stressed and overworked, or better at dealing with stress than all those around them, because they are more aware and know how to manage it.

They can also, just like me, carry scars, and be learning to adapt to new constraints on what they can and can’t do. It doesn’t make you any less of a person, any less capable, or mean you shouldn’t live a full, active, and meaningful life.

If I had lost a limb 8.5 years ago, and then rebuilt my life, to do all I have done since, I don’t doubt I would be celebrated for transcending my injuries, and no one would be talking about what I couldn’t do. Wouldn’t it be great if we treated those who have adapted, and overcome trauma, or any mental illness, in the same way?

Their injuries may be invisible, but their accomplishments in overcoming them shouldn’t be.

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.