Men, Myths & Killing Presidents

Culture

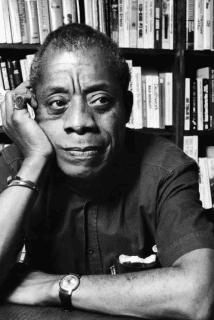

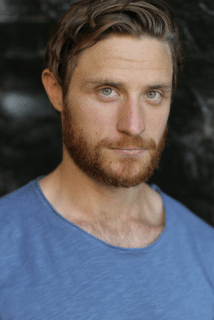

Author Gregg Hurwitz on his latest Orphan X novel about an attempt to assassinate the President, his astonishing level of research, and why men need to confront their fears.

Gregg Hurwitz is probably best known now for Orphan X, his best-selling thriller about Evan Smoak, an orphan trained to be an assassin by a secret government agency. However, with 20 novels under his belt, as well as screenwriting credits and work on comics like Batman and Wolverine, he is the consummate story-telling pro. His latest Orphan book, Out of the Dark, is now available, perhaps his most ambitious yet as Smoak attempts to take down the President of the United States.

We managed to get some time with Gregg when he was in London recently, to find out more about his famously in-depth research – swimming with sharks, shooting with Navy SEALs, plus some more prosaic office-based stuff we’re sure – the psychological theories behind his writing, and the importance of adventure narratives, both external and internal.

On Out of the Dark

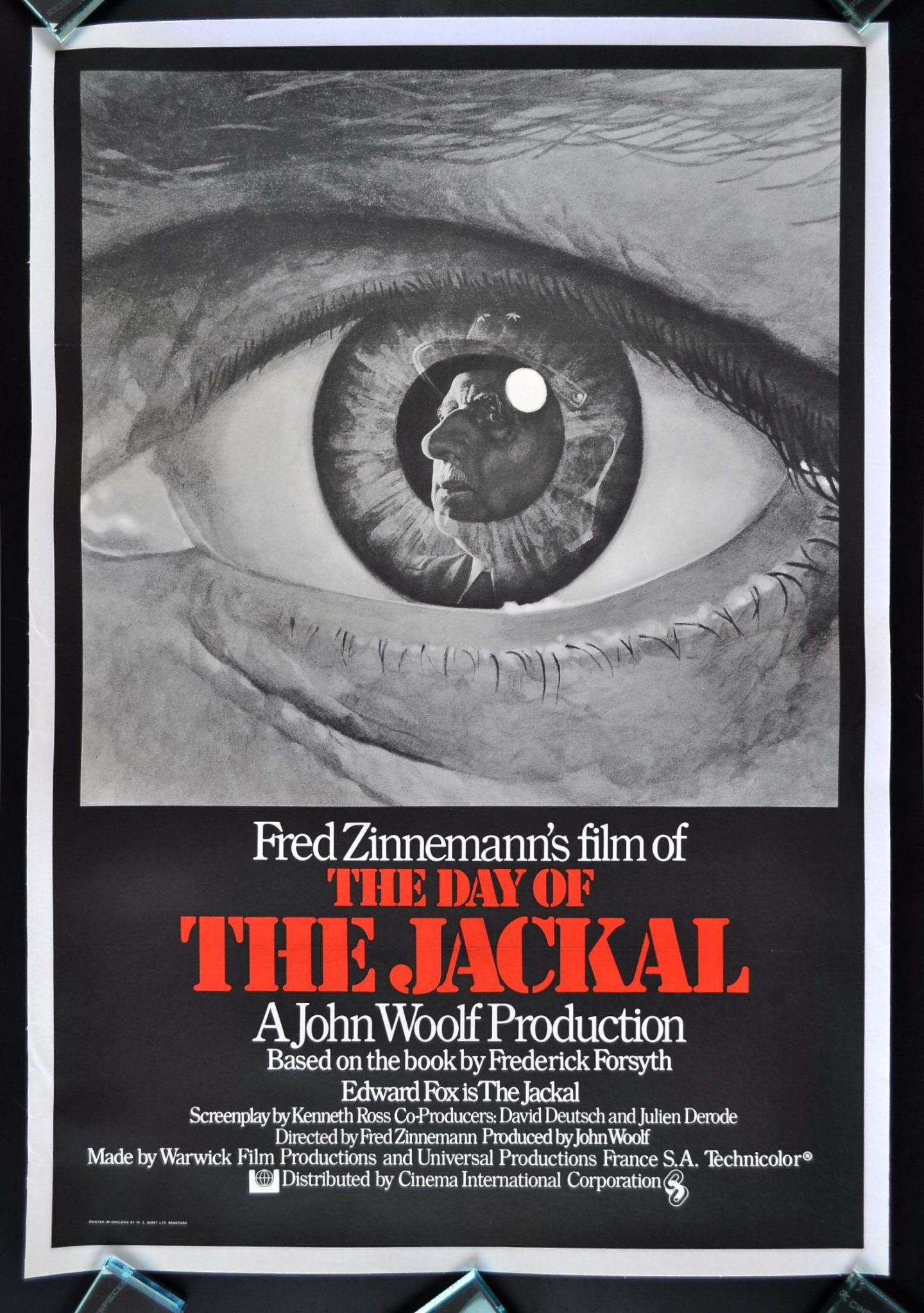

The Day of the Jackal is a seminal thriller and I always wanted to write a contemporary homage to it. It took me 20 novels to make me feel like I had the right skillset to tackle a novel that big. It’s essentially the biggest thriller I could think of. And even more complicated because we’re rooting for Orphan X to assassinate the highly corrupt president.

I really had to build to it. I spent the first two months doing tons of research about all the security procedures. I got the blueprints to Cadillac One, or Beast One, that’s the Presidential limousine, where the doors are as heavy as a Boeing 747. I got info on the entrances to the White House, what the procedures are when the President travels. The first two months were building this wall of possibility in front of me and then I was staring at it like a figure from Game Of Thrones with this giant wall looming over me. I had to figure out how to scale this in a way that felt plausible.

The research is to have the ring of verisimilitude. I’ve done all sorts of stuff, I’ve gone undercover with mind-control cults, I’ve been on demolition ranges with SEALs and blown up cars, gone swimming with sharks in Galapagos. Why do I do it? Firstly, because it’s fun. It keeps me acquainted with the fact that life’s an adventure. But the other thing is it lets me pick the right telling details so that the reader really feels the action. If I don’t do it myself I would be combining all of the usual stuff people have already seen in pop culture in books and movies and TV. And It would just be a shadow of stuff that’s already been recycled.

It’s like I’m trying to carry the reader over the suspension of disbelief. And so the research helps me do that.

What’s crazy is that this is one of the most complicated books that I’ve ever written. Obviously there’s the big A thriller, which is Orphan X trying to take down the most securely guarded human being on the planet. But as he’s pursuing the president I have Orphan A pursuing him. Then there’s this dance going on between him and Candy McClure, who’s Orphan B, and all these other sub-plots, but what’s so weird is this book wrote itself relatively easily. Only in 3 of the 20 books I’ve written have I had a handle on all the way through, and this happened to be one of them. It’s far and away the most intricate, complicated book I’ve ever done and I never lost the thread, which was a total delight. With every other book, in the middle somewhere I get all muddled and turned around and miserable.

On his research contacts

I have a Rolodex at this point of amazing contacts, from porn stars to professors to army rangers to demolition reachers. It’s sort of a mafia process of introduction, so if I need someone in the Secret Service I’ll reach out to a SEAL buddy who once did a joint op with someone in the CIA, who was friends with someone in the secret service.

You always want the guys who don’t want to talk, you don’t want the public information officer, you want the quieter people who don’t tell a lot of stories. And then it’s really about establishing trust with them. So they can go on and off the record, they can give you some information but also come back and say, ‘look I need you to remove this.’ Or ‘we’re going to change 3 things about how we’re going to make that explosive device because we don’t want to make this a ‘how to’ guide.’ So there’s a lot of trust and relationship building.

It’s not about Trump. I put this story in motion well before Trump entered the race. All previous Orphan X books have been building to pushing him on the doorstep of chapter one here. President Bennett, my president, is very different to Trump in a lot of ways and I’m glad for that. He’s very controlled, very focused, very disciplined. I don’t want to be writing something that’s ripped from the headlines because that ages really quickly. I wanted to write a timeless book.

But I’ll tell you this, I’m screwed if anybody checks my search history. It’s all like ‘hotel balcony with best view of the White House.’ If I didn’t have a body of work behind me, I’d surely be in trouble.

On exploring the hero myth in thrillers

I’m a Jungian by training. Carl Jung is sort of my spirit animal. So I believe the hero myth is a necessity for the development of humanity. If you find a tribe in the Amazon that’s been cut off from all human contact, you know they’re going to have eyelids, you know they’re going to have opposable thumbs, and you know they’re going to have a hero myth.

I think the hero myth is a guide and a template that has been evolutionarily selected to show us how we deal with the unknown, both internally and externally. To enact it positively you have to voluntarily confront that which you fear. If you hole up and hide in your castle, the dragon comes and gets you. You have to be voluntarily willing to face that which is scary. And if you slay the dragon, the dragon is always guarding a pot of gold, which stands for self-knowledge. So if you triumph over the dragon, you win back some information about yourself.

I think that’s a template that pushes us a) towards the fact that life is an adventure, do not forget that, and b), to be courageous and c) to be honest, because the unknown internally, represents all the things that we try to hide from ourselves. We put up defences to hide the truth from ourselves, even if the truth is just our own fragility or insecurity or vulnerability. It’s only by confronting all these things that we can integrate them and move forward.

Evan Smoak was raised with the ten commandments from Jack Johns, the ten operational commandments. Never make it personal. How you do anything is how you do everything. But I wanted to counteract that with someone who has been raised properly and not insanely, and that’s Peter the young boy downstairs. He’s raised by a set of rules I took from Jordan Peterson. Jordan Peterson was my thesis advisor when I was an undergrad, and at the time I was helping him edit this book that he wrote. This fairly unknown psychology professor. I thought I’d use some of these rules that he’s writing, this should be uncontroversial, no one knows this guy! I was using these rules as a template towards honesty and orientation of the world for Evan to see a male boy who’s raised properly, unlike the way that he’s been raised.

On the meaning of his books to him

I never realise the meaning the books have for me, psychologically or emotionally until I’m done writing them and then I look back. I started to write these Orphan X books right around when I was 40 years old, and I thought initially they were about the tension between perfection and intimacy. I’d just come off writing Batman for a couple of years for DC, and I’m always interested in Batman, he’s my favourite superhero because he doesn’t fly he doesn’t have a magic ring, he just represents the height of discipline. And the reason why he can do that is because there’s no-one else in his life. His parents are dead, he’s a playboy, so women are in and out of his life all the time. There’s Robin but Robin always dies. He’s alone, and the aloneness is why he’s able to maintain a schedule.

So I thought I was writing the Orphan X books out of trying to integrate how to hold the standards of perfection while having a wife and kids. And also not wanting to be an asshole. Not wanting to give them short shrift, wanting to be honest and available but also not lose an edge and a drive towards perfection, and a sense of adventure that may be masculine.

I kind of thought that’s what the books were about, but when I looked back I realised that I started writing them during a time when I was really transitioning. Transition points occur throughout your life, whether it’s adolescence or retirement, and certainly turning 40 was a big one for me. I started to look around and see that a lot of the traits and habits that have carried me forward, even successfully, to the midpoint of my life, weren’t necessarily the ones that will bring me the most happiness and wholeness for the back half of my life.

I think we all realise that, but it’s hard to let go of the traits that have been useful. If there’s certain characteristics that we know are weaknesses, we know we have got to work on them and let go of them, but some of these things are strengths that just no longer serve us as well.

And as I was looking at all this – I just realised this a month ago, its so embarrassing – I looked back at these characters that I’ve been writing for five years and sure enough, when we first meet Orphan X in the first book he’s just at a certain point, he’s left the program, he’s reestablished himself under his own moral compass and he’s just trying to find his way to a different definition of humanity. And the first book involves him breaking every one of the commandments that are these rules that he’s been following his whole life. So he’s really enacting the same thing that I was wrestling with as a man.

On the importance of danger to explore yourself

A lot of my friends tend to have in their pasts something that’s dangerous. Like I was a pole vaulter, one of my good friends who’s now the CEO of Intel, an amazing man, he designed the fastest computer chip 3 times over, and he’s a stunt pilot. I have a lot of friends who are former Navy SEALs. I’ve noticed I’m drawn to a lot of people who worked in something that involves danger. Even comedy, it doesn’t have to be physical danger.

A lot of times for young men it’s like we’re honing this edge, by going up against life in a way that’s sharpening and sharpening and sharpening us. And if we hone that properly and orient it correctly, at a certain point in life you use that sharp edge to tear through yourself, and investigate yourself in the way that you want to be better. It’s true for women too, I don’t want to imply it’s only for men. Some of that hardening and edge-making that we do in the front part of our life, through danger, through confronting the unknown, through adventure, becomes a useful trip to apply to an internal state. To what you don’t know but what you’re willing to go into voluntarily, and confront, psychologically.

Jumping out a plane is not entirely dissimilar from having a conversation with someone who is completely opposed to your viewpoint, let’s say politically. If you don’t feel like you have to armour yourself with your perspective or corrections or your worldview, you can actually just safely listen and try to figure out what it is they’re saying. And figure out if you can engage with a set of ideas that may be uncomfortable. There’s something in that that’s not totally dissimilar to standing on the edge of the pole vaulting runway being terrified because you have no idea if the pole’s going to break and you’ll smack your head open. There’s an aspect of that when you start looking at yourself, of looking at your own flaws when you’re called to. Going into a conversation where your spouse tells you that you have to look at something about yourself that you don’t want to look at that’s a sign of vulnerability or a fear or something you have.

On the debate around masculinity

Yeah we’re grappling with it right now. There’s a line Jordan has said which I’ve stolen: if you get scared of strong men you should be terrified of what weak men are capable of. And I do think we don’t want to take the edge off men and boys too much. Part of the job is they have to figure out their way through. We have to be tolerant for everybody to be developing and to have a certain amount of freedom and a certain amount of rough edges that the world is honing, and knocking off them. We have to be willing to have boys commit to endeavours that are risky. Obviously I’m not implying this is to encourage misogyny, it’s ridiculous that have to make these designations now, but I’m not talking about stuff that is obviously crassly offensive and should be reigned in, responsibly. But we don’t want to create kids who are really, really timid in any sense. So I’m very much for the rigours of argument and confrontation and risk taking. I have two daughters and I think its good for them to go out and be active and get injured. You’ve heard the phrase ‘helicopter parents’, but my wife who’s a psychologist has heard the phrase ‘lawnmower parents’, about parents who go ahead of their kids to mow down all the obstacles so they don’t even have to have the helicopter. My girls are really active, and my youngest just broke her wrist playing something. We don’t have an approach to protect the kids from all injuries. We have an approach that the kids should be out in the world and active and engaged and having fun, and sometimes when you do that you’ll get injured or make mistakes, but that’s all part of what life is.

On fiction as a relief from puritanical social media

I think we have a lot of people self-censoring because of what the mob will think. I think people are much more reasonable and willing to countenance opposing views than they seem on social media, and I think there’s something like pluralistic ignorance going on where everyone is miserable but can’t talk to one another. The voices on social media creates a chihuahua effect: there’s a small minority of voices but they’re really really loud. And so everyone gets washed up in it and self-censors or gets worried. There’s so much moral outrage and the dopamine hits from moral outrage are so intense, and that’s when you also have people curating their space on social media, that they only get people who think like them, and the more feedback they get, the more extreme they can be.

I do think there’s an important role for fiction not only to explore ideas that are different or complicated or grey, but also to be the kind of stories – especially in genre fiction which again have that basis in writing about courage and writing about honesty – that ask will you really say what you think? Will you really stand up if there’s a more nuanced approach required on a topic even if it doesn’t align directly with one ideology or another? I think we learn a lot of our values and see examples of the kind of morality we want to put forth, in fiction. It’s a good place to explore that.

On improving as a writer

Writing is something you can never perfect. The one thing I would say is very early on I wrote heroes and villains; increasingly I just write protagonists and antagonists. I always want everyone to have a perspective that’s relatable, and the more relatable and smart the antagonist is the more powerful the protagonist is.

The other thing is that when you’re writing a book is that books are the most intimate relationship by far between the writer and the audience. If I sell a million copies of a book, there’s a million different movies playing in everyone’s head. Everyone brings their fears and vulnerabilities and hopes and dreams and aspirations, to a book. What I’m trying to do more and more, is point the reader towards a particular emotion, but leaving enough room that they can fill it with enough room to bring their own experiences to bear. And that’s true for both how fear is developed, how suspense is generated, but also for how other other emotions are generated. You don’t want to tell somebody how to feel or how to think, you want to intimate the direction of it. That’s a dance you try to get better at and better at. Because there’s a dance between me and every single reader and the more that I can build the scaffolding around the sentiment that every reader can individually fill, the better I’m doing. But that’s a skill that takes a lifetime to try and attain.

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters for the best of the site.

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.