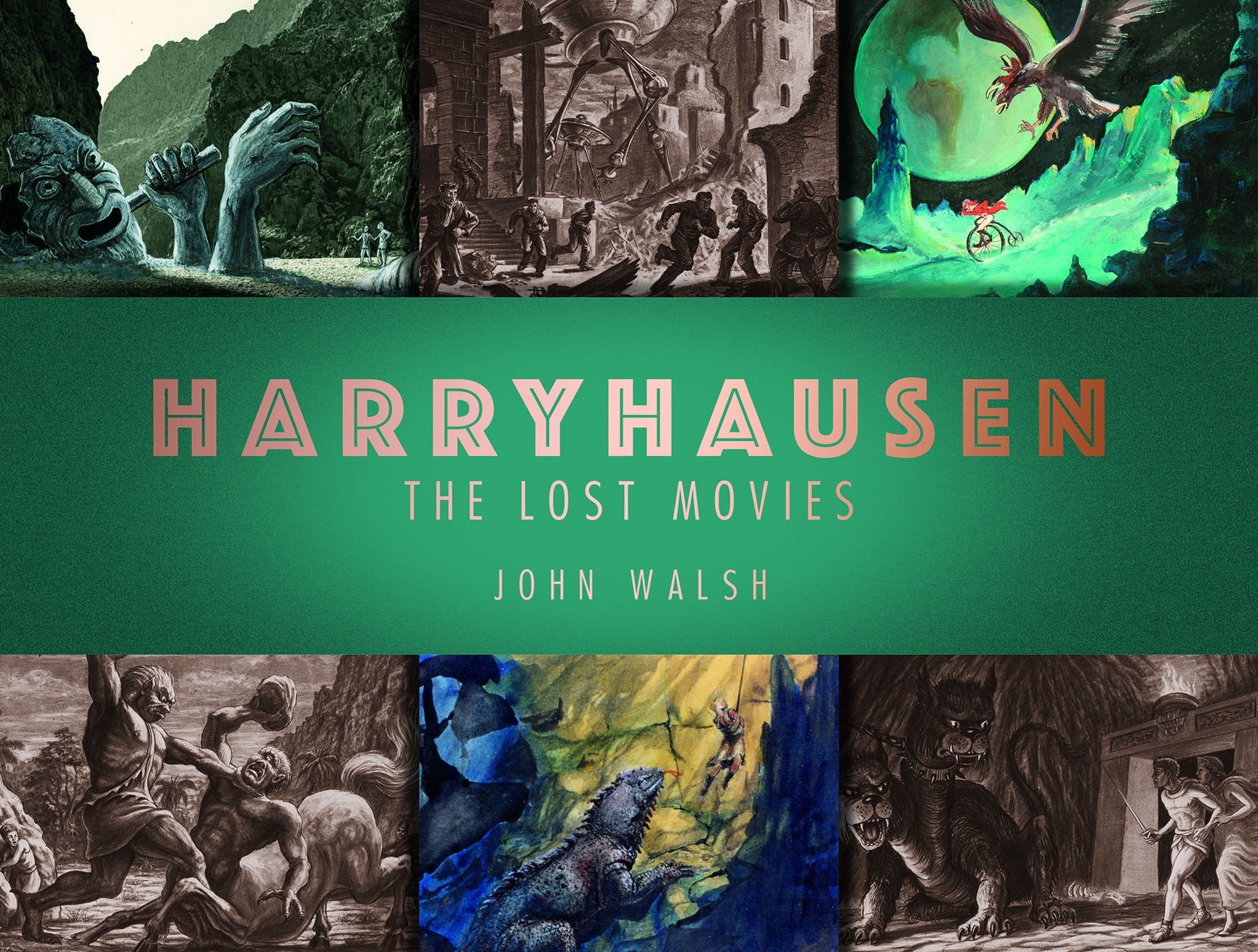

The Lost Movies of Ray Harryhausen

Culture

Ray Harryhausen is unquestionably the greatest film visual effects artist. Here his friend John Walsh talks about the new book Harryhausen: The Lost Movies.

For people of a certain age Ray Harryhausen is a god. And thanks to his films still being TV favourites on a Sunday afternoon, that means people of every age. With Clash of the Titans, Jason and the Argonauts, the Sinbad films, One Million Years B.C., and a host of others, Harryhausen became effectively a genre unto himself. Who directed these films? Who knows! We instead know them as Ray Harryhausen films, such is the genius so on display in his visual effects, with his monsters creations possessing such with incredible personality; put the films on for children now and you’ll see immediately how caught up they become because his characters are simply gripping to watch with an uncanny power which has never been matched.

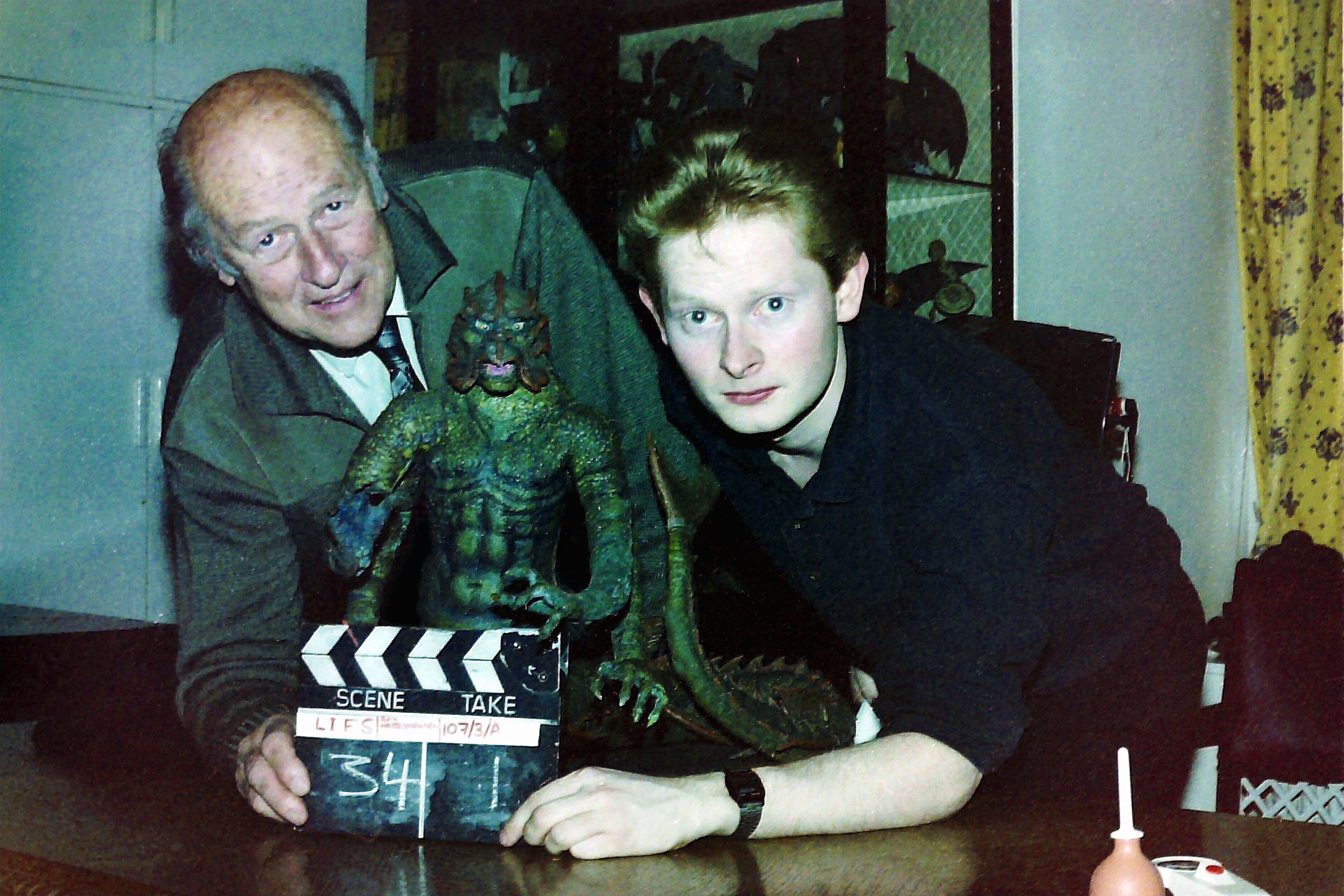

John Walsh was a teenage film-maker when he first met Harryhausen and made a documentary about him. The two became friends up until Ray’s death in 2013, and John is now releasing an unmissable book about some of the lost works from the archives. It offers tantalising glimpses of work that was developed, sketched, and even shot for test footage, but which for one reason or another never made the light of day. We managed to grab a quick chat with John about the book, what Ray was really like and what made his special effect so, well, special.

Can you give us an overview of the book and its particular angle?

Harryhausen: The Lost Movies explores Harryhausen’s unrealised films, including unused ideas, projects he turned down and scenes that ended up on the cutting room floor. As a filmmaker, myself, I am acutely aware of the time and effort that can go into a project that never sees the light of day.

When did you first meet Ray? How did your friendship develop?

I first met Ray was I was an 18-year-old student at the London Film School. That was unusual as the course was post-grad and the other students were in their mid-twenties or older. I looked incredibly young, even for my age, so I would often wear black to make me look older. Not sure this worked. I was a winner of the BBC Young Film Maker of the Year when I was 15, so this helped propel me and after a successful interview found myself at one of the most prestigious films schools in the world. It was the late 1980s and when it came to find a subject for a documentary. I knew that Ray Harryhausen lived in London. I found his telephone number and address in a telephone directory. I made the call, and that changed everything. Ray was impressed that I knew so much about his films and animation technique. I was a fanboy by today’s standards. I kept in touch with him over the years, and he would look at my various film and TV work as I progressed as a writer, producer and director. In 2012 I started to record commentaries for Ray’s films in his house.

Can you give us some perspective on his special effects work compared to special effects today?

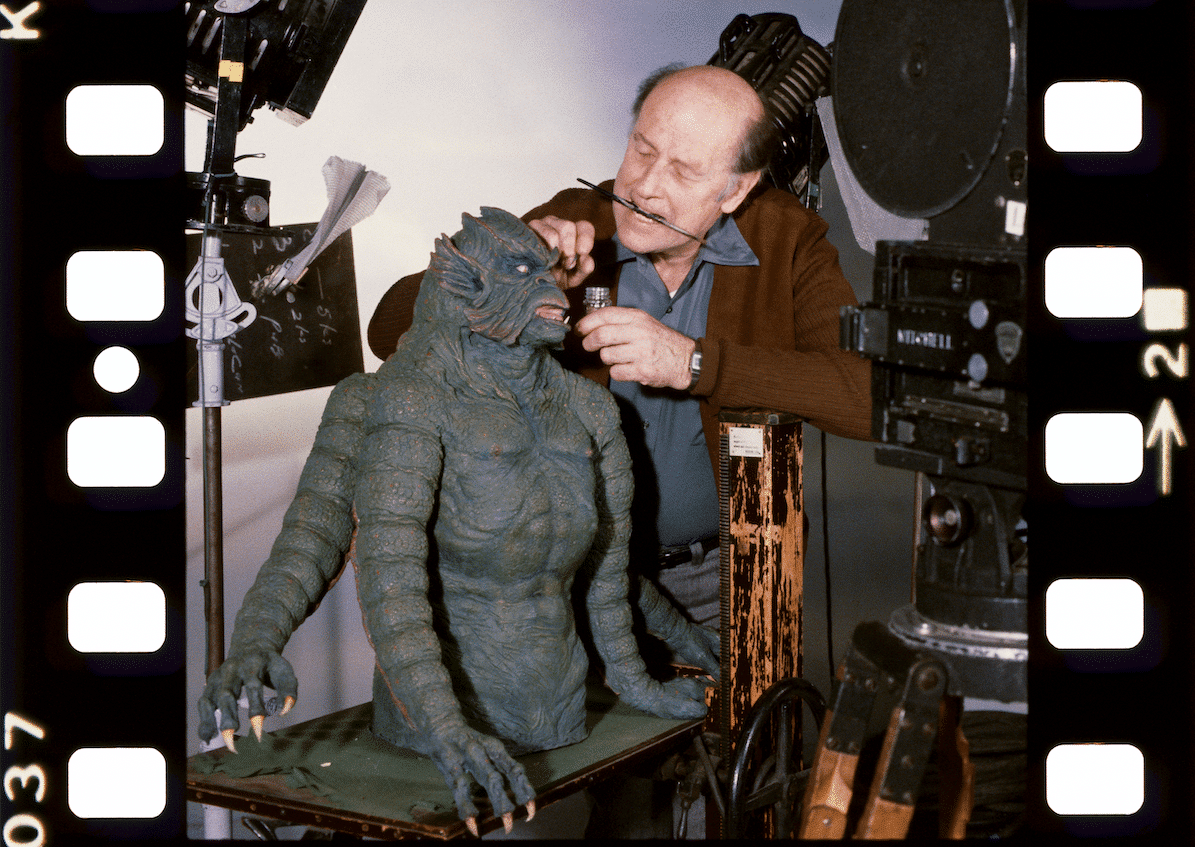

Ray’s work was the Jurassic Park of its day. He would animate small models, painstakingly, through tabletop stop-motion photography with each model being moved once for every frame of film, 24 times for each second on screen. In the last twenty years, computer graphics had taken over the area of on-screen creatures. In the last few years, there has been a significant resurgence of stop motion animation with films like Isle of Dogs, Box Trolls and Kubo and the Two Strings.

How would he practically work with directors etc on the films? Would he storyboard? How much freedom did he have within the films? Did they have to work around his vision?

Ray would be the producer on most of his films and would choose the director who would best work with him and have a clear understanding of the technical process. It was essential for Ray to direct those scenes that involved compositing live actors and a fantastical creature on screen. The artwork I have uncovered for Ray’s unmade films reveal significant production concept art that would have been used to pitch an idea to a studio boss. These would then form the basis for the production design for the film if they secured a green light.

His work is so fondly remembered that he transcends the films themselves, and is almost a stand-alone genre to himself – why is there so much love for him do you think?

At the time of each film’s release, they were just part of the cinematic landscape. It was after Ray retired that his work was reassessed and his contribution was seen more than just a technical achievement. You are right to suggest that Harryhausen is a genre. George Lucas said that “without Ray Harryhausen, there would likely have been no Star Wars.” The performances of the creature are from one man and not a workshop of people. The performance, therefore, is an accurate representation of the original artist’s vision. If you were making a similar film today with hundreds or sometimes thousands of CGI tech teams, then a production needs to adopt a house-style that everyone can work towards. This can have the effect of stifling creativity and individual performance and nuances that bring a creation to life. So while Ray’s technique may have been superseded by technology, early computer graphics films have not aged well, while Ray’s films are being lovingly restored by the studios. On the 15th September, I will be hosting a premiere screening of the 1958 classic, The 7th Voyage of Sinbad in 4k with stereo sound at the Regent Street Cinema in London. In sixty years, I wonder how many CGI films will be receiving a special screening.

Can you tell us about a few on these ‘lost movies’? What were some of the key projects, the most enticing work? Were they passion projects that could never get made?

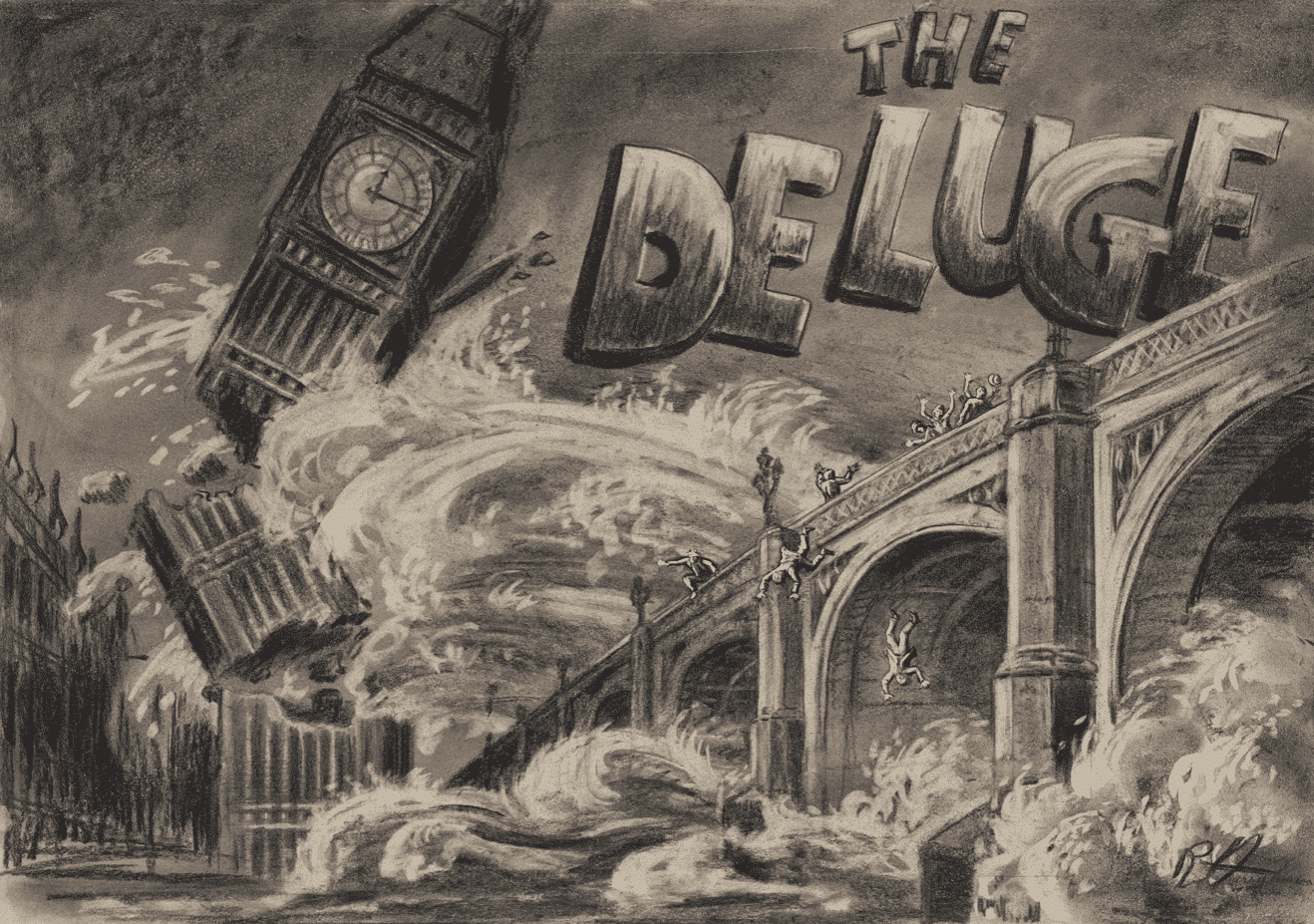

Some of the lost movies were passion projects, such as Dante’s Inferno. It would have been too shocking for audiences and as Ray told me in my student film, “I wonder very seriously how many people would want to sit through an hour and a half of the vicissitudes of tormented souls.” It’s perhaps less surprising to read that there were unmade dinosaurs film or Sinbad adventures, but even I was amazed by the depth and breathe of the work and subject matter. Ray also turned down the first Marvel movie in 1984 when Stan Lee sent him a script for the first X-Men big-screen adventure. Ray was beaten to the punch by his old employer George Pal, twice first for War of the Worlds and then later The Time Machine. One of the reasons Ray seldom talked about the unmade films was due to the secrecy around ideas, which at the time were a currency that could quickly go up or down. Ray has his finger on the pulse of the audience even if he couldn’t convince studios bossed. In the late 1960s, he wanted to revive the disaster genre with his remake of The Deluge which would have seen London flooded by a giant tsunami. The 1970s were awash with disasters films from The Poseidon Adventure, Earthquake, The Towering Inferno and the Airport series. Ray also wanted to secure the right to the Conan novels in the 1960s. His brand of mythology and monstrous creatures would have worked well. The ultra-violence of the stories scared off the backers. It would not be until the 1980s that Arnold Schwarzenegger would wreak bloody carnage in his onscreen portrayal and prove that it would work for cinema audiences.

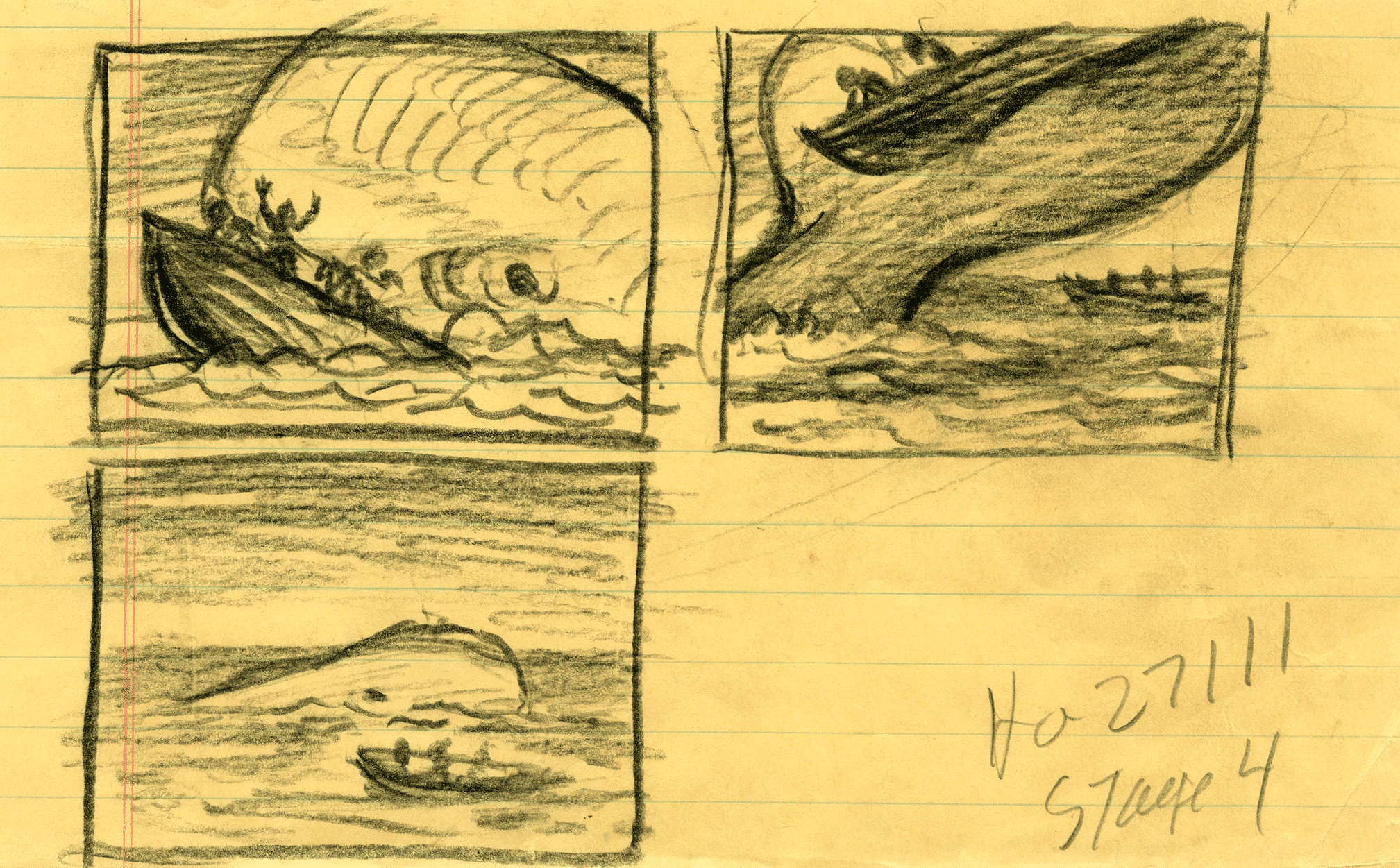

Artwork for The Deluge disaster film, developed in the late 60s.

What were Ray’s ambitions in this respect? Was he happy in his career or were there things left hanging?

As a creative and busy person, Ray was always thinking of the next film. When I started writing this book, I estimated that there would be about 45 to 50 films within the pages. The finally tally was nearly 80. I had to turn detective to track down the artwork and stories. Ray was not happy that so many of his films went unmade. After Clash of the Titans in 1981, Ray planned a bigger and more ambitious project, Force of the Trojans. The book features unseen artwork, test footage, scripts and sculptures. His outlook was a positive one. For the Lost Movies book, I canvassed the views of five famous film directors for the book’s forward. They shared their opinions on their own unmade films and those of Ray Harryhausen: John Boorman, Guillermo del Toro, Mike Hodges, Nicholas Meyer, and John Landis.

What did you make of him as a man?

For an industry that is perceived to be insular, selfish and cold. Ray was a very generous man with his time and views. I was an 18-year-old film student when Ray took the time and allowed me to make a documentary about him. He was fascinated by other filmmakers and those who were drawn to his unique brand of animation. Ray was undoubtedly my cinema hero, so I was overwhelmed with meeting him, but I could not have imagined at the time what a pivotal moment making this film would be in my life.

Artwork for Force of the Trojans.

What were the characteristics that allowed his work to be so inspired?

While other filmmakers were making monster movies. Ray never thought of his creatures as monsters, but misunderstood creatures. His approach was to imagine a world and environment where these creatures would live. When you introduce the human element, that is where the conflict lies. It was the approach that Steven Spielberg took many years later with Jurassic Park.

What is your own personal favourite Ray scene, and why?

My personal cinematic epinine would be The Golden Voyage of Sinbad. It has some of the most iconic creatures and sequences and inadvertently changed the face of 1970s TV. A BBC producer called Barry Letts was looking for someone to take over the leading role of a long-running TV series. After seeing the Golden Voyage of Sinbad, he was so impressed with the actor who played the villain, that he called his agent and set up a meeting that ended up with Tom Baker being cast in Doctor Who. I persuaded Tom to narrate my student film about Ray, you can see a clip of this in the book’s trailer below.

What inspiration do you personally take from him for your own work?

My work has been mostly in television documentary with two feature films in the cinema so far. It is a counterpoint in many ways to Ray’s fantasy genre. When I would speak to him about my work, we discussed the possibility of fusing both areas. A documentary approach to Clash of the Titans would have given the film a very different look and feel. However, the locked-off camera needed to achieve the special effects photography would have made a handheld film an impossibility. Ray liked the idea that Force of the Trojans could use this approach, it is a shame that he will not be here to see the results. I have set up a new film company, Ray Harryhausen Films Ltd to develop Force of the Trojans after forty years of sitting in the archive. I have written a new storyline and brought together the production design and creature artwork.

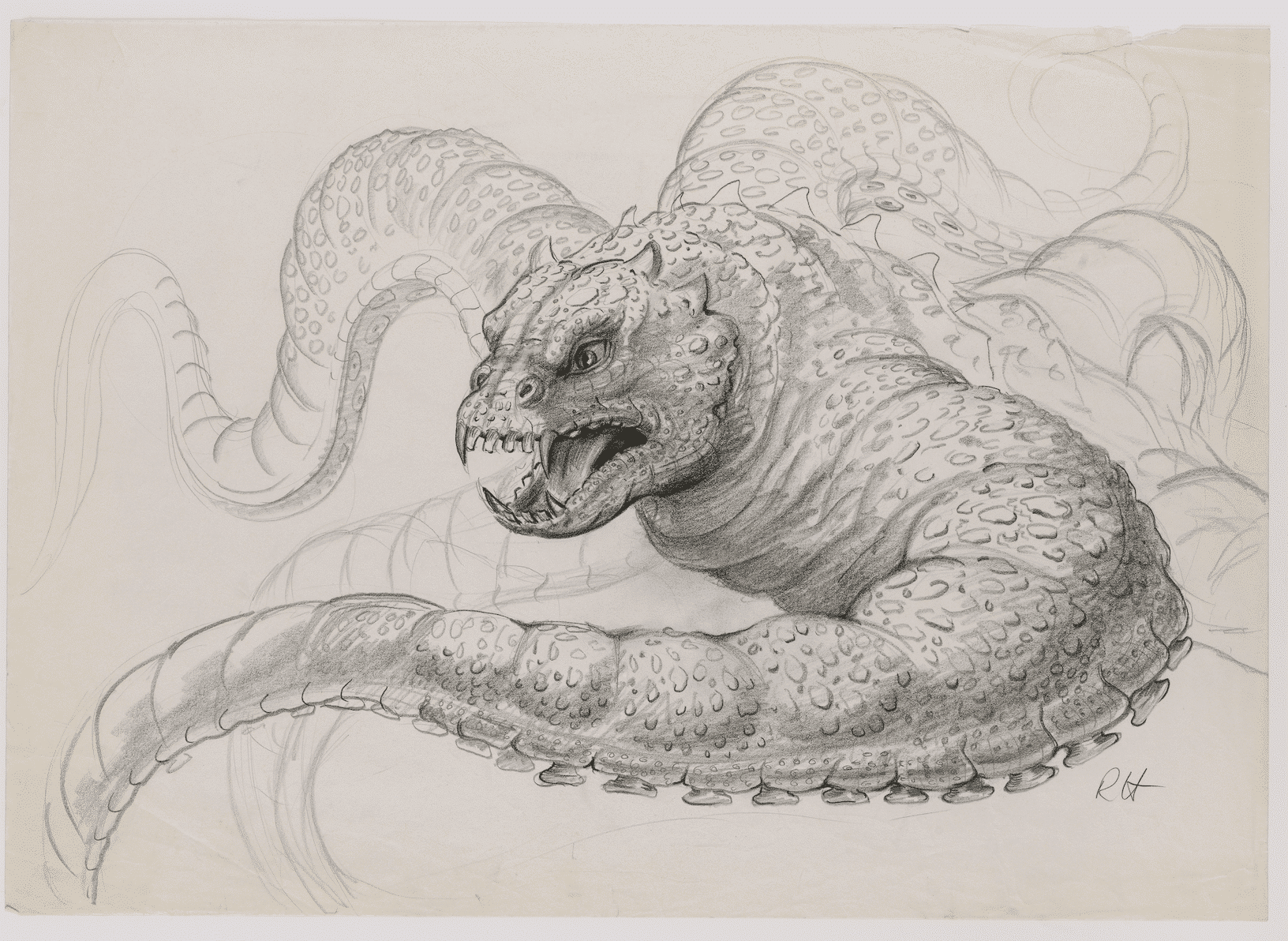

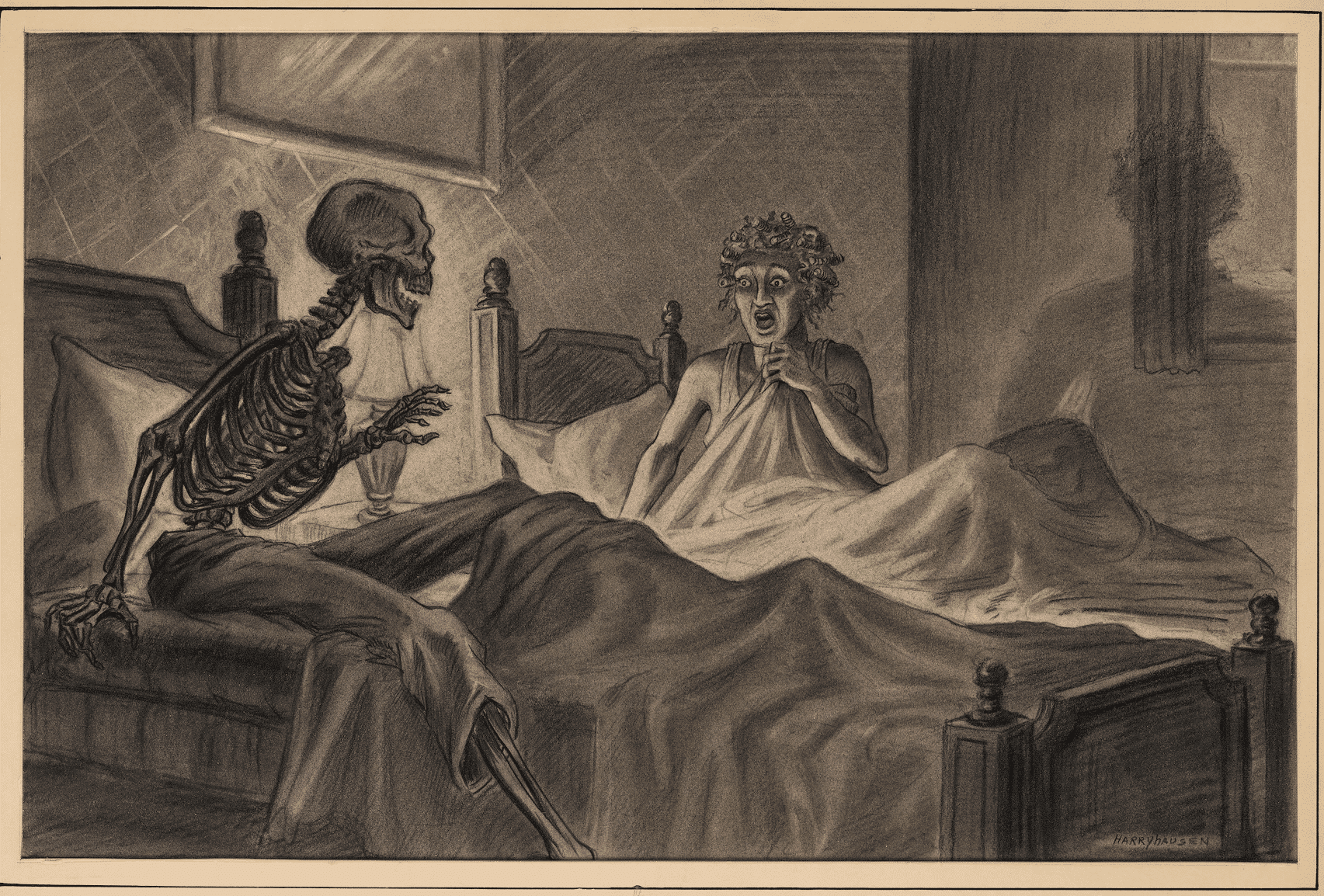

Artwork for Skin and Bones, and sketches for a version Moby Dick.

Can you gives us an idea of the cultural impact of his work?

When Ray’s films were released, they were not held in any higher regard than other films of the day. However, sixty years on Jason and the Argonauts is amongst four of Ray’s films to get a full 4k restoration from the original, films elements. Other movies from that era with more prominent stars, larger budgets and in some cases Oscars have been forgotten. It is a testament to the longevity of his work that it has survived new trends in film making and special effects. I will be presenting a premiere screening of the 4k restored 7th Voyage of Sinbad on 15th September at the Regent Street Cinema at 3pm here. Few filmmakers could expect to have this treatment of their work decades on. Today’s filmmakers recognised the debt they owe to Ray and the influence it had on them becoming filmmakers. Without Ray, the fantasy and science fiction cinema scene would be a barren place indeed.

What’s the most memorable thing Ray ever said to you?

Ray once said to me “don’t get old.” He lived to a grand age of 92 and was lamenting the passing of his many friends. He also meant that I should keep a childlike outlook of wonderment on my perspective as a filmmaker. This Lost Movies book is a testament to his optimism of a filmmaker whose light was never dimmed by the rejection of his industry peers.

I will be signing copies of the book at the legendary Forbidden Planet on Sunday 15th September at 1pm, here. For years, I would window shop as a schoolboy and film student at Forbidden Planet and queue for other signings. Despite all my successes and awards, I never imagined signing my own book at Forbidden Planet.

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.