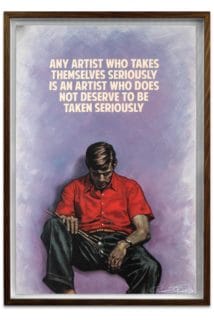

‘Some Words Of Advice To The Young’

Culture

Short fiction by The Connor Brothers' Mike Snelle about a man trying to reconnect with his daughter. "All my life I've been a liar..."

All my life I’ve been a liar, and that’s the truth. I lie even when I don’t need to. When there’s no point. Take the other day. My phone rings and it’s one of those cold calls, the ones where they tell you they’ve been informed you’ve been in a car accident in the past two years, and might be eligible for compensation. Before she’s even finished speaking I launch into this whole story about how I got blindsided at a junction. The car was a write off, I say. Injuries? Don’t even ask. Hairline fracture to my right arm. Neck sprain. Mild concussion. A laceration on my left cheek, just below the eye, that required fourteen stitches. There’s still a fragment of glass lodged in there. Was off work for three weeks. Had to wear a neck brace for six. I haven’t been in a car since. Can’t face it. The thought terrifies me. By the time I finish she’s already spent her commission on a dirty weekend in Sardinia. I’ll put the forms in the post, she says. When she calls back a few days later to check I’ve received them I pretend to be a woman and tell her she’s got the wrong number.

At sixty-seven, I’m too old to be making prank calls. It’s undignified.

Hello?

Oh hi. It’s Gerry. You might not remember me but we went to school together. Feels like a lifetime ago. You came to mind the other day. Not sure why. I hadn’t thought of you in years. I was overcome by this undeniable urge to get in touch.

Gerry??

Yes. Who’s this?

Margaret. Margaret Osborne.

Oh great. Margaret. It is you. For a moment there I thought I’d got the wrong number.

And so on.

The success rate is variable. Sometimes they figure out they don’t know me in a few minutes. Others, we’ll spend an hour or more reminiscing about events that never happened involving people I’ve never met. More than once someone has suggested that we meet for a catch up, and I’ve had to tell them that I live in Norway now, and work on a government ethics committee which safeguards natural resources for future generations. The key is sustainability, I say.

Every morning I walk to Starbucks on Burley Street and order a cappuccino to go. When they ask for my name I tell them I’m called Harry, or Barry, or Larry, or Gary. If I’m feeling particularly rambunctious I’ll pluck a name from further afield. Santiago perhaps, or Jinn Woo. Not once have any of the morons who work there shown the slightest indication they know I’m lying. Imagine going through life so blinkered by your own petty existence that you’re blind to the universe all around you. What a waste of all that aliveness. Maybe it’s because I’m old. Young people disregard the old because they don’t want to have sex with them. It’s true. Think about it. Who wants to fuck a geriatric?

I was never handsome but now I’m nearing the grotesque. All ears and nose. Skin that doesn’t fit properly. Over the years my penis, never impressive, has shrunk in exact proportion to how much my nose has grown. It’s as if they’re exchanging places. One of the curiosities of getting old is watching your body betray you. As a young man I believed that I’d become more attractive with age. That I was one of those men who took time to ripen. A late bloomer. By thirty I’d look like Steve McQueen. By forty Robin Redford. Every morning I looked in the mirror and was disappointed.

Some words of advice to the young: in matters of the heart, avoid perfectionism. Perfect love is a myth peddled by cynical middle-aged white men whose job it is to sell records. Actually, avoid love songs altogether, unless written by either Leonard Cohen or Johnny Cash. And don’t watch movies which feature a man and a woman who are clearly in love but don’t realise it yet, and when, during the climactic final scene, they eventually do come to realise what we already know, live happily ever after. The end of the movie is only the beginning of their story. They will face serious challenges. Adversities. Sometimes those challenges will prove insurmountable. Some of them, despite their best efforts, will get divorced. I myself was married three times and each time left for something better. Sometimes the something better is the thing you’ve already got.

Another thing – don’t name your children after famous people. It is never good to have to live in the shadow of your parent’s heroes. You are destined to disappoint. Very few people called Janis can sing, and barely any of the ones that can sing die of an accidental overdose. Mostly women called Janis work in calls centres and spend eight hours a day phoning strangers to ask them if they’ve been involved in a car accident.

When someone tells you that you can’t do something, it usually means that they can’t do it. Take last month, Dr Ford tells me I can’t come off my medication. It’s too dangerous, he says, no doubt dosed to the eyeballs himself on Prozac and Valium. What’s wrong with a little danger? I want to ask. I’d never have climbed Kilimanjaro if I was risk adverse. Never ridden a motorcycle through Cambodia. I certainly wouldn’t have slept with that ladyboy in Hanoi in 73. The dong on her. I’ll never forget it.

And how do I feel now? Great. Fantastic. Never better. So what if sleep is elusive? I’m old. Hours count. Sleep is wasteful. And my thinking? So much clearer. I’ve been returned to myself. Gifted a lucidity I’d forgotten I’d ever lost.

Of course Iris wants to see me. Why wouldn’t she? I’m her father.

When I knock on her door it’s opened by a man I’ve never met, accompanied by a toddler whose inquisitive expression and cherubic features leave me in no doubt that this is my daughter’s child. I ignore my son-in-law and with considerable effort crouch down to meet the child at his own height. I’m your grandfather, I announce, fighting back tears. We study each other for a few seconds, both of us feeling a bond so powerful it can only be explained by our shared genetic heritage.

I’m sorry, interrupts a voice from above, I think you’ve got the wrong house. Who exactly is it that you’re looking for?

Iris, it turns out, lives in the flat upstairs. I wonder if he’s been fucking her. Fucking my daughter. Having an affair. Why else would he be playing father to my grandchild? Does Iris even know that she’s a mother? That the kid she sees every day playing outside is her own?

After careful consideration I realise what I had momentarily mistaken for a family bond is in fact one I share with all children. An innocent’s ability to see the world anew each and every day. An insatiable appetite for experience. A near religious respect for the sanctity of all living creatures. A sense of profound wonder at the unbearable beauty of the universe. And so on.

There’s no one home so I wait in the hire car I’ve parked on double yellow lines outside. Let them give me a ticket. What do I care? I’ve abandoned more cars than I can even remember. Lost the keys and walked away. Tired of them and left them in car parks at train stations. Run out of petrol and deserted them at the sides of roads. How we laughed, Iris and I, when a charcoal grey Volkswagen I owned was confiscated by the police because I didn’t have insurance. Let them have it, I said, I’m not paying any fine. We’ll buy another. She must have been eight, or nine. As we walked towards home I imparted some hard won advice. Resist authority at every opportunity, I said, particularly your mother’s. If she or any of your numb-skulled teachers tell you to do something, you should do its opposite. In particular don’t trust anyone whose authority is derived from a uniform. Uniforms are expressions of moral cowardice and dim witted obedience. And make no mistake, suits are uniforms in disguise. Do you understand what I’m saying? I asked. My legs hurt, she replied, how much further is it?

We were close you see, Iris and I. Not just regular parent and child close. She was myself reincarnated. Sometimes just to look at her brought me to tears. I owed it to her to teach her all the things I wished I’d known earlier in life. I didn’t want her to make my mistakes. I wanted her to make new mistakes. Better ones. Mistakes that began where mine ended. Mistakes I couldn’t even dream of.

I’m woken from one of the power naps I’ve recently started to take by a knocking on the car window. A middle-aged woman is mouthing something through the glass. Possibly an irate neighbour who objects to my casual attitude to parking restrictions. Or an undercover traffic warden. The father of my grandchild is standing arms folded on the pavement behind her. The kid is nowhere to be seen. I close my eyes and attempt to psychically convey a message – I don’t recognise your authority so you might as well give up and pick on some other poor sucker, but she’s too agitated to receive it. I wind down the window and am about to give her a lecture on how in Stalinist Russia people like her ratted out their neighbours and were part of an architecture of fear and oppression that facilitated genocide. Hitler’s Germany too. Mao’s China. Modern day North Korea. There’s no such thing as an innocent pawn, I’m about to say. But she beats me to it.

Dad, what the fuck are you doing here?

I begin to protest a case of mistaken identity but when I look more closely I see that it is her. Hiding behind the pinched bitter mouth and pained expression, she’s there. My daughter. My Iris. But what’s happened to her? Where has her innocence gone? Her wonder? She’s not at all what I’d expected. She’s older. Harder. Frumpier. She looks nothing like a critically acclaimed but seldom read poet. And what is she wearing? Some kind of uniform? I’m winded by the realisation that her life must have been more difficult than I had hoped. Her disappointment at it is etched on her face. Poor child. What happened to you? Where did it all go so wrong? Was it him? Did he trample our dreams?

Maybe he hits her, this man I don’t know.

What are you doing here? she asks again, feigning anger for reasons that are becoming clearer by the second.

I ignore her and address him.

You, I say, pointing a threatening finger, keep your hands off my daughter. Touch her again and I’ll punch you in the spleen.

Jesus Christ Dad. What the fuck is wrong with you?

She looks over her shoulder.

I’m sorry Tony. He doesn’t know what he’s saying. He’s not well.

Not well my arse, I reply. That’s your mother speaking. Tony has something to tell you. Tell her Tony. Tell her about the boy. Tell her about my grandchild.

She starts to cry.

Don’t do this Dad, she says quietly. You can’t do this. It’s been seven years. You can’t just turn up here like this unannounced. Not when you’re like this. It’s not ok.

I want to tell her that I’ve come to rescue her from a life of mediocrity. To get her back on the right track. We can live together, I want to say. It’ll be just like it used to be. The two of us against the world. You can start writing poetry again. The kid can come too. I’ll take him to the park while you practise spoken word and work on a prize-winning novel. You’ll dedicate it to me and give a tearful speech at an awards ceremony in The Albert Hall, thanking me for my unwavering support and constant inspiration. I want to tell her all this and more but she’s crying and it hurts my heart and the words won’t come out.

Can I come in? I ask.

She shakes her head.

I think you’d better leave, Tony says, she doesn’t want to see you.

Why is she with him? He’s an idiot. Even his face is stupid.

The two of them share a brief conspiratorial conversation that despite trying, I cannot hear. He stands there looking puzzled for a moment, before telling her that he’ll be downstairs if she needs him. It’s true. That’s what he said. I‘ll be downstairs if you need me. Moron. When he’s gone I ask her again if I can come in and this time she doesn’t refuse. She just turns and walks away. As I follow her I notice that even her walk is heavy with wasted opportunity. Maybe that’s why she’s upset. Because I remind her of everything she could have been.

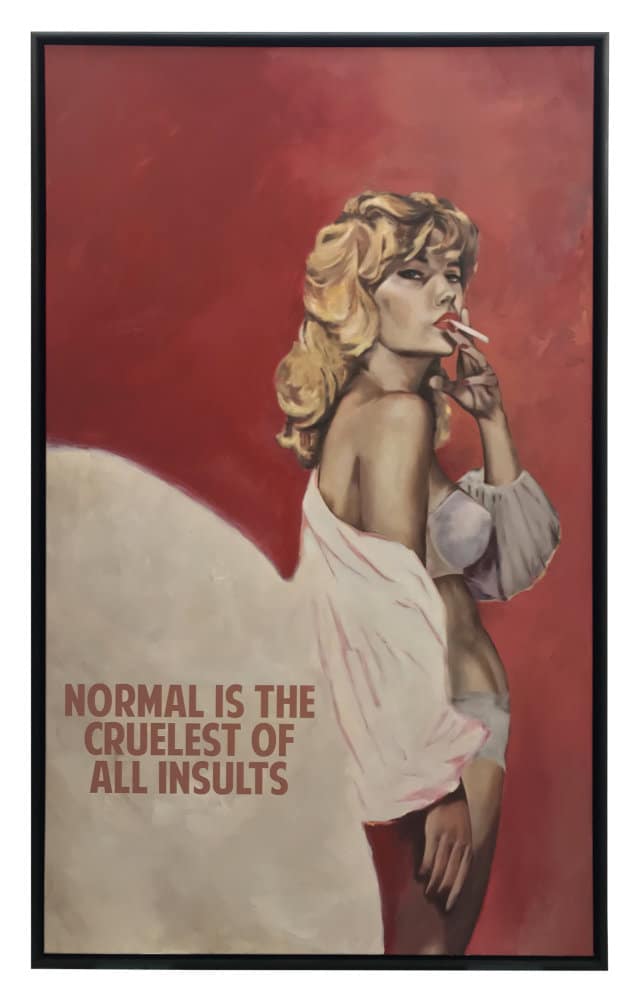

My daughter’s home is ordinary. Unremarkable. Boring. There is nothing worse than being called ordinary. Normal is the cruellest of all insults. Mentally, I begin to make changes. A wall covered with quotes from overheard conversations that will provide inspiration for her novel. Books filled with annotations strewn across the living room floor. A framed photograph of the two of us on the kitchen wall. Empty wine bottles. Full ashtrays. A human skull on the coffee table to remind her that life is finite and time is precious.

We can fix this place up in no time, I say.

I don’t want it fixing up, she replies angrily. I like it like this. What are you doing here? What do you want?

Can’t I visit my only child without wanting anything? I’ve come to help you. To save you from… this.

What’s wrong with this?

Nothing, I say cautiously, nothing at all. It’s very nice. It’s just, you know, a bit… normal.

I want normal, she replies. I need it. It’s taken me years to learn how to be normal. To understand that holding down a job doesn’t make me a failure. That stability is not synonymous with idiocy. That suicidal depression should not be an aspiration. That it’s an illness and not a side effect of genius.

She’s so lost. I should never have left it so long. So what if she told me she didn’t want anything more to do with me? I should have persisted. It was my duty to steer her. I’ve failed her and look what’s she’s become.

Do you remember that poem you wrote? The one about the dying oak tree? About how the lightning struck and set it ablaze so that instead of slowly fading away it set the whole forest alight?

She’s sobbing now.

It was beautiful. You wrote it for me as a gift. You can’t have been more than twelve or thirteen. It’s the best present I’ve ever received.

Stop Dad. Please.

‘His burning brilliance was matched only by that of the sun which for so many centuries had nourished him.’ You were so gifted. You probably still are, beneath all this.

I can’t do this. I just can’t. You’ve got to go.

Tell me about my grandson, I say.

Grandson? What grandson? What are you talking about?

Is now the right time to tell her? Sooner is probably better than later. She’s lost too much time already. There’ll be a custody battle, that’s for certain. The kid will be ok. He’s too young to know anything about it. It won’t even register as a memory. Anyway to have two parents fight over you isn’t the tragedy people think. At least he’ll know he’s loved. We can raise him together. Gary can stay involved. Weekend visits. School holidays. He’s probably not as bad as he seems. It’s important for a child to have a father.

I’m thinking a Moroccan themed bathroom, I say. Brightly coloured tiles and a mirror with little doors you can open. A rug hand woven by Bedouins. A fez hanging on the back of the door. Incense burning constantly. Somewhere to find sanctuary after a day’s creative struggle.

Dad. Please. Stop. Why are you here?

I don’t know how to answer. There is so much I want to say that I don’t know how to begin.

The problem with your mother is that she lacks vision. Mistakes unconventionality for illness. I tried to tell her. To show her that it was possible to break free on the constraints of societal norms. To think for herself. If anything you should feel sorry for her. No point in being angry.

I’m not angry with her.

She looks tired. Ground down. Like she’s given up. I need to find the hidden spark that I know must still exist within her. I need to find the words to bring her back to life.

This isn’t you, I say, gesturing around the room, it isn’t us.

I reach over and gently lay my hand on her shoulder.

You’re not a failure, I say, and you haven’t disappointed me.

She shrugs me off angrily.

Get the fuck away from me. Get the fuck out of my life. I don’t want you here, don’t you understand? You’re toxic. How many fucking times do we have to go through this? This is why I can’t see you. This is why Mum left you. You’re too selfish to take your medication. One minute it’s this and the next you’re trying to hang yourself in the garage. Don’t you see? Don’t you understand what it does to us?

She pushes me in the chest. Keeps pushing me. Pushes me all the way to the door.

I never want to see you again, she screams. Get the fuck out of my house.

Then suddenly it’s gone. Her anger. Suddenly she’s small again. Just a child. I don’t know what to say to make it better. I’d take it from her if I could. Take all her anger and disappointment and make it my own. The two of us stand in awful silence in the doorway. Seconds become minutes. I don’t want to leave. I can’t face it. I just want it to go back to how it used to be when she was little.

I’ve got cancer, I say quietly.

For a moment she stares at me in disbelief. Then she slides down the wall, and covers her face with her hands. Watching her cry I realise how much I’ve missed her. How much I need her in my life. For a long time neither of us speak.

Where is it? she asks when she finally looks up. Can they operate?

I shake my head.

Chemo?

Too far gone.

I sit down next to her on the floor and put my arm around her. She buries her head into my chest. For a moment everything is as it should be. Like it used to be. This is all I ever wanted. To be close. Countless times I’ve held her like this. After a bad day at school. When her first boyfriend broke up with her. The time the dog got run over by a milk tanker and we buried it in the back garden. The familiarity of it fills me with a sadness and a happiness too overwhelming to comprehend. I stroke her hair and tell her everything will be ok as her tears dampen my shirt.

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily emails for the latest from the frontline of modern mascuinity.