Olly Hawes: is it even possible to be a good man?

Masculinity

My experience making performance about men, by men, for men (but also for everyone else too).

Okay… I’m going to start this article by writing about theatre. If you’re one of the 4% of people in the UK who go to the theatre regularly, great. But if you’re not, please don’t worry. This isn’t an article about theatre, it’s about modern masculinity – it’s just that in order for this article to arrive at being about modern masculinity, I am going to tell you a story about a theatre show I made.

Earlier this year, after about half a decade in the artistic wilderness – partly self imposed, partly imposed upon me by the pandemic and having kids – I took a one man show to the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. It went well (hurrah), and has just transferred to Riverside Studios in London, where it is playing until Christmas.

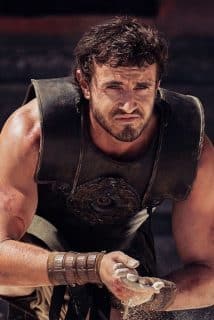

F**king Legend draws a comparison between the state of men, and the state of the world, and suggests that both of those things need to radically change – and if they don’t, we’re all probably fairly fucked.

The show begins like this:

This is a story about an English, middle class, straight, white, cis male.

And it is a story written by an English, middle class, straight, white, cis male.

And it’s a story told by an English, middle class, straight, white, cis male…

‘Yes!’ I can hear you all think it! ‘Excellent!’ ‘Finally!’ ‘This is exactly what the world needs right now!’

I know, I know.

On the surface, F**king Legend is a pretty simple story about a fairly annoying bloke who cheats on his girlfriend on a stag do, but weaved into that story are layers and layers and layers (and layers and layers) of irony and metatheatricality.

This begins with the performer (me). Is he an actor performing a role? Is it the writer making a confession? Or a narrator weaving a series of complex layers of metanarratives? It continues with the main character:

So this story is about me… or maybe it’s not.

Maybe it’s just about someone who looks like me… or maybe it’s not.

Maybe it’s just about someone who fits my description… or maybe it’s not even that.

Maybe it’s about one of you…

Maybe you’re sitting next to, or near to, the person this story is really about.

The point is, when I’m telling it, you can picture whoever you want. Whoever it’s useful for you to

picture, picture them – but it should probably be a man.

The journalist and reviewer Fergus Morgan compared F**king Legend to Sarah Kane’s Blasted (a play that was so shockingly violent, and shockingly unusual in its form that it indelibly changed British theatre – and, indeed, British culture – when it premiered in 1994).

In that play’s first act, a man and a woman argue in a hotel room, with the man exercising power over the woman in a variety of ways; the play’s second act depicts a horrific war torn world. Kane described the relationship between act 1 and act 2 as the acorn and the tree: one leads to another.

I was very happy that a prominent journalist made this comparison, not just because Kane’s a hero of mine (she is also, by the by, one of the litany of brilliant female artists to have killed herself), but also because it’s accurate: I am making the same link Kane made 30 years ago (albeit in a very different way).

So, you might reasonably think the world doesn’t need another story about ‘middle class, straight, white, cis males’, and yet this is the demographic that still holds more sway than any other, it is undeniably an integral part of the British condition and it is, I would argue, the demographic that defines the world – the direction we’re going in, and how we’re getting there – more than any other… So maybe, actually, the world does need more stories about them.

All of this is to say, my show explores the perfidious influence of modern masculinity on men themselves, and on the rest of the world. And it does this both through the things that actually happen in the story (which begins on a stag do, but ends in a refugee camp set in a dystopian world of climate breakdown); but also in the way the story is told, as it shapeshifts from one mode of telling to another, as it creates questions about whether the story is about one man, or all men; whether it’s a true story, or made up; and whether I, as an artist but also as a person, actually think what I’m doing is helping improve the state of modern masculinity and the world, or whether the whole thing is just some sick nihilistic joke.

And yet, the ultimate irony about a show that is so laced with irony, is this: in writing and performing a show about the perfidious influence of modern masculinity, my wife – my ever understanding and supportive partner – and my children (one of whom is a girl), had to make considerable sacrifices – emotional sacrifices, temporal sacrifices, financial sacrifices.

This means the very conditions in which the show was made directly contradict the values the show is apparently espousing. It is this, more than anything, that I think is the defining characteristic of living in the developed world: even if you can be bothered to try to be good, any attempt to do so is tainted in one way or another.

When I started writing the show, I had a question in my mind: is it even possible to be a good man?

If you’re here, reading this article, on this website, you’ve probably wrestled with the question, and you’re probably familiar with the arguments both ways. Yes, of course it’s possible, it’s simply a case of living as well as you can. No, of course it’s not, the structures that we all cannot help but inhabit are so intrinsically misogynistic that it’s impossible for men, the greatest beneficiaries (willingly or not) of these structures, to ever be considered truly ‘good’.

There was something else I had in mind when I started making the show, a sort of yearningly empty mantra, which was this: When I look at the world I don’t know whether to laugh until I cry, cry until I’m dead, or just quietly do well the things I have control over. I still don’t know. And, I would posit, the issue we have right now, as men, in 2024, is that most of us don’t really know.

And yet, despite everything, I think we could be in an exciting moment for masculinity. There is a chance to evolve it as a concept and as a practice. Our economy and our culture are in decay – but we can’t let that turn us into permanent pessimists and cynicists, hope is an obligation, and so is trying to make a better future. For the time being, I’m going to muddle along trying to do that. The problem is, I’m just not really sure how to.

Olly Hawes: F**King Legend is at the Riverside Studios, London between Wednesday 13th November to Saturday 21st December. For tickets, visit: https://riversidestudios.co.uk/see-and-do/fking-legend-136800/

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.