Trauma, Addiction and SAS: Who Dares Wins

Mental Health

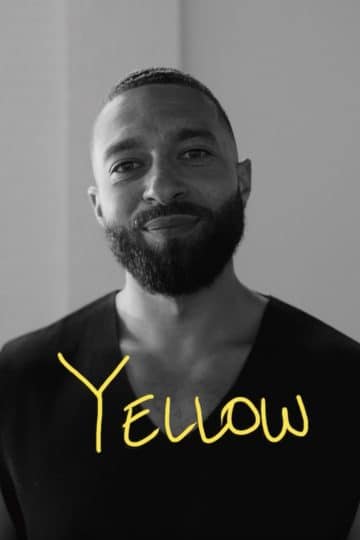

James Gwinnett tells the story of a rugby injury that sent him on a downward spiral, and how he regained his confidence and fitness, via one TV show, and now a new challenge...

On 9th February 2013, my world changed.

It was admittedly a sheltered and privileged world, and largely still is, but it was one that gave me purpose. Playing semi-professional rugby, I was disciplined in my weekly routine, eating the right things and training hard to be the best that I could be come game time on Saturday afternoons.

Around 60 minutes after kick-off on that fateful day, I did something I’d done thousands of times before over 20 years of playing the sport: I flew headfirst at an advancing opponent. The rugby alter-ego was in charge with no consideration for the welfare of the body that it was throwing into the contact situation.

At around 17 stone at the time and charging headlong into a similarly sized opponent, the impact was brutal. And the mistimed collision left me reeling, clutching my shoulder in agony. But only for a short time, because the human body is a truly bizarre and remarkable thing. 15 minutes – and an ice pack – later, I wanted to return to the pitch.

Fortunately, the team physio saw sense, insisting I see out the game on the touchline, and I dismissed the aches and pains as the regular post-match stiffness. It was only 48 hours later, on the Monday night, whilst lying in bed in agonising pain from head to toe, that my body finally told me there was something seriously wrong.

After four hours in A&E, two X-rays and a CT scan, the severity of the situation revealed itself; a crack in my C6 vertebra. I’d broken my neck, impacting my spinal cord in the process, and narrowly avoided paralysis.

From a young age I’d always harboured dreams of making it as a professional. Though admittedly ‘past it’ in playing years at the age of 28, the news that my career was over was heart-breaking. Three months of enforced work leave – and the dreaded statutory sick pay – only served to make me more miserable. Stuck at home, alone, the boredom set in. And the continual, nagging question, “What’s the point?”

I took to drinking to mask the spiralling despair. A vicious, three-year-long rollercoaster ride of self-medicated boozing ensued. Daytime drinking. Binge drinking. Secret drinking. It’s only in hindsight that I’m aware I was depressed.

In my journey to sobriety I’ve met all manner of inspirational people from former drug addicts to ex-cons and I’ve tried to compare myself to them. “I wasn’t as bad as that,” was my thought process. “My problems are pretty trivial.” But, as one of those former addicts – now a close friend – pointed out to me, struggles are struggles. They’re all relative. And depression doesn’t discriminate.

Even my privileged background didn’t help. In fact, it probably compounded the issue. I’d never really stumbled across any of life’s roadblocks until that point and hadn’t developed the necessary coping mechanisms.

‘Rock bottom’ is another relative concept. Mine came at the literal bottom of a bottle of Jack Daniel’s, finished in one sitting in a dingy hotel room. I had what could be described as an epiphany the next morning, as I battled with a fried breakfast, my stomach complaining as I attempted to feed it bacon and eggs. “Never again,” I thought. Not a casual, half-hearted, “I’ll never drink again.” A sincere and definitive, “I WILL NEVER DRINK AGAIN.” I hit the lowest of lows in that moment, realising how desperate and pathetic I must have looked to anyone who might have bothered to pay me any attention.

Bizarrely, in giving up my addiction, my addictive nature truly came to the fore. With AA meetings, hypnosis, therapy, counselling, seminars and pouring through literature, I became addicted to staying sober. And my saviour? My higher power? Something that I was well acquainted with, although we’d fallen out of contact; fitness.

Because, as I mentioned, the human body is a remarkable thing and as someone that has suffered through something as severe as a broken neck, I’m fully aware of its fragility. But, on the other hand, the human body is capable of incredible feats when pushed to its limits.

Watching the London Marathon in 2016, I was inspired by the tens of thousands of people pushing themselves to their limits. Fancy dress, charity runners, cancer survivors, octogenarians, you name it. I was compelled to take on the challenge. I registered the very next day and began my training, breaking the 26.2 miles into digestible chunks over the course of the following year.

On completion, my addictive nature again kicked in and I found myself pondering my own limits. Various marathons and ultra-marathons on different continents later and that bulky former rugby player has transformed into a (slightly) leaner endurance athlete. I’ve also been lucky enough to take part in SAS: Who Dares Wins, Channel 4’s brutal show that puts civilians through a condensed version of Special Forces selection. I didn’t do too badly, either, as one of the final eight ‘recruits’ that made it through to the infamous interrogation phase.

Now almost [as of 26th March] four years sober, I continue to push my own limits. A multi-day ultramarathon awaits – in the heat and humidity of Sri Lanka, no less – and then a 100-mile run along the Thames.

Sri Lanka has a certain poignancy to it. Joined by some of my fellow SAS recruits, all of whom have first-hand experience of mental health issues, we’re taking on the challenge of running 250km (six marathons) in five days. In doing this, we’re raising money for the Mental Health Foundation, so that funds can be used to combat the stigma of these issues and raise awareness of the need to talk about our problems. Too many people, men in particular, still feel like they can’t open up and it leads to suicide being the biggest killer of men under 45 in the UK; amounting to almost 5,000 men taking their own lives in 2018.

Thus I continue my journey of recovery with the aim of helping others to take a step towards their own. It doesn’t matter if it’s addiction or mental health issues or both. Because, as the saying goes, it only takes one step to begin a thousand-mile journey. Or a 250km journey through Sri Lanka. Or a 100 mile one along the Thames.

Find me on Instagram at @jamesgwinnett and please donate to our Sri Lanka challenge at:

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.