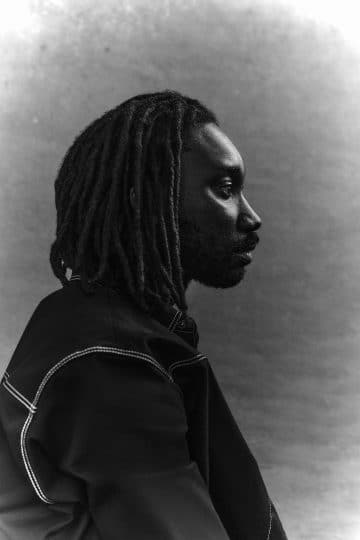

Paul Rhys on Saltburn, Men Up and his working-class roots

Culture

Paul Rhys has blown up recently with his roles in Saltburn and Men Up, but his stellar career has been a triumph over a tough background growing up in Wales.

“This is the kind of work I want to do now. I want to help people.” So says Paul Rhys, actor and human extraordinaire. A man who was part of the three highlights of the Christmas period, Men Up, about men struggling with their sexual and mental health as they took part in the first Viagra trials in the Nineties, Ridley Scott’s Napoleon, and then Saltburn, the explosively wild Talented Mr Ripley-meets-Brideshead Revisited film that blew up over the holidays as families gathered to scream in horror at some of Barry Keoghan’s antics. Paul played the butler Duncan, following brilliantly in the footsteps of a glorious history of unnerving ‘help’, from Mrs Danvers in Rebecca to Grady in The Shining.

Gen-Z must surely now be on the case when it comes to Paul, but of course he has had a stellar career on stage and screen for many years. Films such as Robert Altman’s Vincent & Theo, Chaplin opposite Robert Downey Jr, were early stand-outs. In theatre he was nominated for an Olivier Award for King Lear, and played Hamlet at the Old Vic, among many other roles. He’s a true acting hero, one who has also picked up a natty line in playing vampires on TV, in Being Human and Da Vinci’s Demons. What many people might not know, is how interesting a life he had prior to his acting career – indeed, Man Up is he coming somewhat full circle, as it’s set in Swansea, near where he grew up in working-class Neath.

As he tells us, he didn’t have an easy start in life, his dad died young, his mother depressed and he was essentially a street kid – but he certainly had something driving him, becoming an entrepreneur in his early teens, getting himself into a good school and then hitting London where he became an avid Bowie fan, clutching a copy of Aladdin Sane, and taking sudden notice of actors and acting. The rest is history, except it’s one that must surely be told in his autobiography one day. Here’s our interview with a most inspiring actor…

Can you tell us about Men Up please?

It’s set in Swansea in 1994. It’s a true basis for the story. Pfizer did their first clinical trial on what was to become known as Viagra in 1994 in Swansea on a group of five type one diabetic men with erectile dysfunction, which is a common side effect of diabetes. And my character is Tommy Cadogan, who’s gay and for that reason, is thrown off the trial. A lot of it is about prejudice and survival and it’s a sort of tragic comedy. It’s light hearted, but packs quite a punch, actually.

I think men struggle enormously with anything around virility. Men struggle to speak about anything at all that could affect the perception of themselves in the world. And women have an easier language, I think, in this kind of discourse. Men struggle unnecessarily. I think impotence is difficult where men are supposed to be priapic and phallic at all times. It’s a dominant phallic world. And it’s preposterous. Literally a myth, I think, based on the myth about Priapus, from Greek Mythology.

I hope it does have the capacity to touch people and I hope if I could reach one person and make them feel seen, I’d be very happy with my work in this.

Russell T Davis was involved in it, wasn’t he?

Yes, he produced it and I gathered, guided the script, and Matthew Barry wrote it. Ashley Way directed. It’s a one and a half hour film, which used to be quite a common event on BBC, but now it’s quite an event having a single film. There are soaps and there are limited series, but nothing quite like this. There used to be quite lots of them when I was growing up.

But of course, he’s got Doctor Who on at the same time. Russell is like a whole industry down there. Maybe they should rename South Wales, DavisLand. Welcome to DavisLand. They should have a smiling picture of Russell as you go up over the southern bridge.

What aspects of your character did you particularly enjoy putting across?

Well I was born down there in a very very very working class environment. My parents didn’t go to school over the age of 13 or 14. I never get a chance to play [a person from this background], I’m always either super powerful, super aristocratic, super brainy or Beethoven or immortal but I’m very rarely a person and it’s nice to be that.

And I like being a gay male. I liked feeling the truth of that and feeling about prejudice. I’m queer. Though when I grew up, I loved women and I loved men, I’ve never made a distinction at all. I’ve not been that sexual actually to tell you the truth. I’ve never had a one night stand. I’ve only ever had deep compassionate relationships with people I was mad about but people is the operative word. I’ve never had anything casual in that way. I’m not like that. I just tended to have deep relationships with a few partners. I don’t know why I’m telling you all this…!

But yes it was nice to play someone from that area. It was nice to be with the other boys who were from that area too because there’s a shorthand, the humour is the same and there are things you’d forgotten.

When I was doing Saltburn, one of the security guards came up to me and she said, ‘Oh Paul, you’re from Neath aren’t you?’ I said yes. She said, ‘do you say “landed?”‘ And I’d forgotten, everybody used to say landed. I’d never heard it anywhere else. It’s like, ‘how did it go?’ ‘Oh it was wonderful, I was landed.’ It means like to be totally happy with the result. ‘Oh I’m landed with it.’ Have you ever heard that?

I’ve never heard that before. I’m going to use it. Just dipping into Saltburn: it looked like the kind of film that would have been amazing to work on. Was it?

I’m such a huge fan of [director] Emerald Fennell. I’d seen her film Promising Young Woman and I just assumed she did loads of films. Then I realized it was her first one, which was genius. I literally thought, ‘how could I ever get to meet this woman?’ I had no idea she was doing another film. And about a week later, this offer came through. I couldn’t believe it and I would have done anything in it, actually, but Duncan was a fascinating character.

We all felt we were making something worthwhile with a visionary director, and that’s such a wonderful feeling. We felt it with Ridley [Scott] too [on Napoleon]. Ridley is definitely a visionary and has made some of the greatest films ever. But, yeah, Saltburn was a very happy experience. We were all very connected. I actually lived near the house, in this cottage, they gave me a room there so I could feel more Duncan-ish. It was was a wonderful summer. It seemed to take forever, but it was wonderful.

Are you still going on to these sets trying to learn things?

Yeah. Somebody said to me, ‘did the young actors learn anything from you?’ I said, ‘I learned from them.’ You’ve got to. I want to keep fresh. I want to keep on learning. I want to be pushed. I don’t want to feel like I know anything. I don’t know anything. And every time I go into anything on stage, I’m like, ‘oh, I can’t do this’. It’s been like this from the beginning. ‘Oh, why did they ask me to do this? I can’t do this. I can’t do these huge roles. Let them get somebody else.’ And I think that is a working-class male problem.

I was not brought up to have any idea of myself as anything. Special, or not special, just anything. My mother said to me, literally, when Tom Stoppard, had written a play for me called The Invention of Love, and we were at The National. She sat in my dressing room and they all came in, the dressers, the makeup, all of that, and she said, ‘All this fuss. Nobody’s going to be looking at you.’ As I went to the stage, I thought, ‘she’s probably right’. It was only years later, I was like, ‘who the fuck do you think they’re going to be looking at?’

I don’t know. If you’re not brought up like this, it’s a bit late in life, so I go towards everything thinking I can’t do it. I’m full of fear. And I work my arse off. That’s why I work so hard, because I’m frightened.

So it has some benefits in some ways? But it seems very different to how kids are brought up now, to think they can do anything.

I was told to shut up. We couldn’t win. It was so hard. I think if I had a child, I don’t have children, but if I did I would spoil them. Spoil them and make them feel like they were the most wonderful, wonderful, wonderful, unique creature in the whole world.

But then they wouldn’t be set up for life, perhaps. What would they do if somebody starts telling them they’re not good at something? I don’t know. I don’t know everything. Look, the position I was in, it’s amazing that I wasn’t crippled by it and couldn’t function or just hit the bottle very young, as most of my family have. I just didn’t. I took the pain, turned it into something else. And that’s what Jung’s idea is, isn’t it? Take what is negative and turn it into the energy. Like the energy of envy can become the enormous, brave power to heal the world. But you have to make the conversion inside yourself.

Did you have this sense of that when you went back to make Men Up then? Did that bring a some stuff back for you?

I rarely talk about it with people because they always want you to say it’s all wonderful to be home and it is wonderful, but it’s complicated. It’s often the source of trauma for most of us, if we’re honest. So whilst I do love being in Wales, it’s also a deeply traumatic place for me because I didn’t have the easiest upbringing and a lot of that comes back.

It was small minded, as the film reflects, actually. It was small minded and being queer and different and a bit divergent generally didn’t go down very well all the time. So it’s quite a frightening place in many ways, but the world was different then. I don’t know what it’s like now.

It is a complex thing going back. It’s beautiful in many, many ways, of course it is, but it’s also got shadows there lurking and they’re cold and a bit terrifying.

Who were you working with out there as well, though, in terms of the other actors on Men Up? Was that aspect good for you?

Yeah, I knew some of them. Mark Lewis Jones I knew and Steffan Rhodri I’d met before. They were lovely. My part particularly, but all of the parts in different ways, were intensely emotional parts. But they’re also funny. They used to make me laugh. Joanna Page is hilarious. We’ve worked together an awful lot before. That part of it was beautiful. The director’s a lovely man. The producers were wonderful. We were in this freezing factory in the middle of nowhere and there was snow everywhere. We’d be going into these heartbreaking scenes and then come out and laugh for a couple of hours. It was great. They’re wonderful people, all of them. Very happy job, actually.

In terms of being an actor, is it a cathartic thing for you? Is it a chance to explore different aspects of yourself like that?

Yes, I do think it is. I don’t know what would happen to me if I hadn’t found acting. I think the depression would have gone berserk because I’m from a family of depressors and I think I’d have found the substances. But I found a way of releasing, particularly perhaps on stage, I found a way of getting in, channeling very intense emotions. And that does have a healing. I mean, it’s a difficult one because it’s the character that’s being healed, really. You are healing yourself, perhaps, but it’s one step away from actual self discovery.

It’s just one character out for me, anyway, very true. I funnel myself through these things in a very personal way. No matter how different the character are, I’m always very true in the role. It’s coming out of me, I’m not putting on stuff. I’ve got to feel it or I can’t do it.

It is a release, but it’s not a resolution. I would say, but I think men and mental health is a big conversation. Partly men up hits one some of it. I think some of the aspects of this are to do with men’s sense of themselves in the world, in various ways.

How do you look after your mental health now?

Well, like today I ran and I do circuit training in central London, outside the park in Russell Square. Today I meditated too. I don’t touch alcohol. I don’t touch drugs. I eat a very disciplined diet, but I have done for decades otherwise. I know. I think sugar is a drug as pernicious as any other drug. Worse than most, actually.

That just about keeps it away. Because if I don’t do those things, it’s nipping on my heels in minutes. This is another thing. Men have got to start talking about it. We have got to open up with each other, with friends. And publicly we’ve got to share our stories and our vulnerabilities and our fears. Freud thought the only authentic emotion was fear. The only one. And that everything else was a tributary from that central fear. And I think that’s probably right.

And a particularly difficult thing for men to admit as well, on that basis.

I think it will change. And I think the younger generation are very at ease with their feelings. And I think the future is in that way marvellous, I think.

My father died young. I never got to know him. Some lucky people are very close to their fathers. My house was divided between my mother and my father. I took my mother’s side completely. And it was only later on I thought, oh, God, I’d love to have known him. I’m more like him than her, actually. Which of course you don’t realise when you’re young. But he died of this inherited heart problem in his forties, so I didn’t really know him. My mother lived till she was 90.

Where did you look for people who could teach you or look after you?

I was quite an enterprising boy. I obviously realised that whatever I needed wasn’t in the house I was born into. So I adopted myself out to all these childless or funless families right within this tiny little street. We lived in Charles Street, next to the cinema. Two up, two down. I was the adopted son of at least three to four families. The day we were leaving, when we moved, they were all crying because they were losing their son.

I must have realised I was neglected, so I was free to do what I wanted. My mother was too depressed to notice and my father just wasn’t there at all. So I just used to drift around and speak to strangers. I was doing all the things that you tell children not to do. I was definitely the one that would have gone in the van with the man with the sweeties. It would have been me, for sure. And I went to the cinema on my own, when I was about five. I knew the people in the box office, but it was a social world, or we thought it was. And I looked in nature with animals. I found love with animals.

I absolutely adored my mother. I did everything for her. But I also knew that as a mother, she wasn’t functioning, but as a person, I adored her. I was a very independent little boy. I had a little business by the time I was about ten. I know it’s ridiculous. I was making more money than my father, in my teens. You couldn’t make it up. I used to buy foals, horses, mature them and break them in and sell them. I learned all about that from other farmers I became adopted into. I lived on farms even though my parents had never been near a farm. I’ll have to write about it at some point.

School wasn’t much of a thing for me, especially after we moved. I went to a terrible school and stopped going for about two years until they finally caught me. Then I got myself into a very good school when I was 14. But I had all the time been reading. All the time. Always had a book. Never kids books, I was straight in with Dickens. When I was about 14, I couldn’t tell you where China was on a map but I’d read more than undergraduate level.

And I found myself when I was reading plays – when I got to the good school – relating to these characters in a very, very emotional way. Crying and screaming through these plays on my own. That must have been saying something but certainly it didn’t mean I was thinking I should go to drama school. I’d never seen a play. I didn’t know you could be an actor. I hadn’t been near a theatre, we had nothing. I saw movies but I thought of them as distant stars who weren’t real. I can only imagine something unconscious must have formed at that time.

Then I was up in London, going down Gower Street, and I can remember this so clearly all the Georgian houses and it pouring with rain, I was on a bus on the top deck and I looked to my left and saw all these people running around through the window and it said Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts, and I just thought well these are the luckiest people in the world, what can I ever do to go there? And be with them. And that’s how it started.

Then I used to go to the theatre and thinking that was something I could do, but I didn’t think I would get in or anything.

I was a terribly shy child but I find that with actors, particularly the more intense ones, very shy awkward people not at all flamboyant, or extrovert. Often the better ones are cripplingly awkward and I would definitely fit into that. I’m not very good socially, I’m often embarrassed and will hide away from things. How did this all ever happen? God knows. I still don’t understand why I do it. I really don’t!

Men Up is on BBC iPlayer now

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.