The Incredible Story Behind ‘Flash Gordon’

Culture

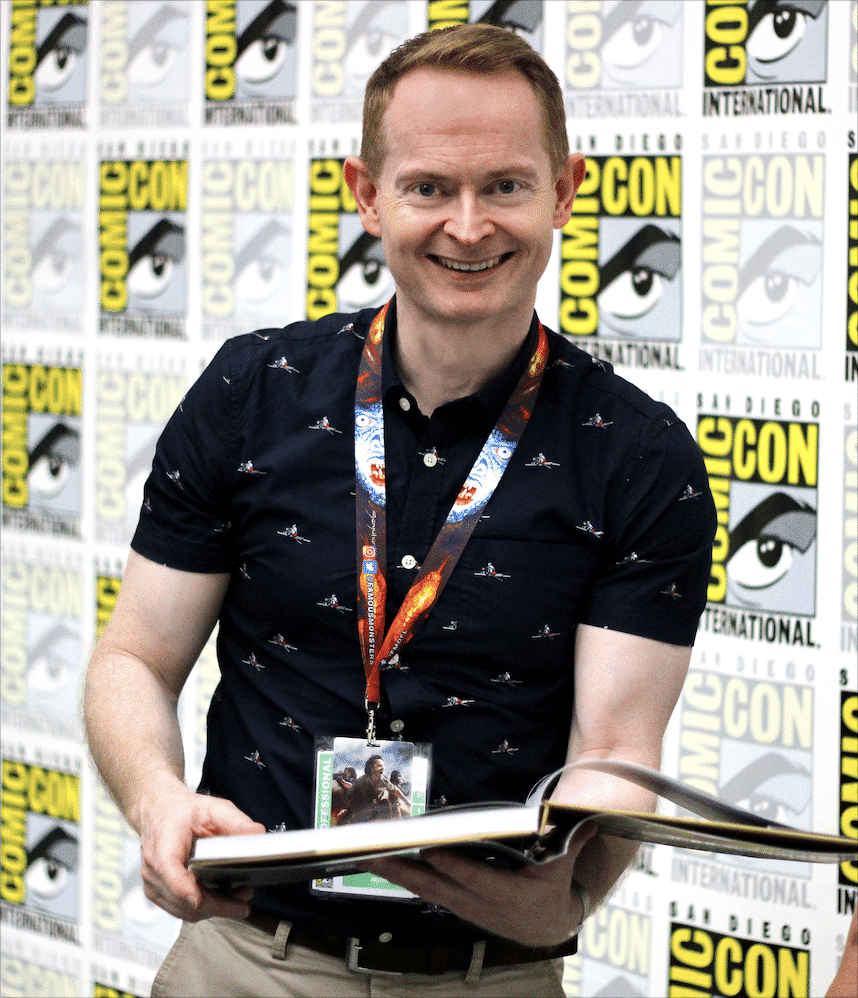

Author John Walsh on the troubled making of a pop-art classic, and why writing his new official book of the film was no easy task either!

On December 11th, 1980, Flash Gordon hit cinema screens in the UK. At the time the country was heading into a deep recession, and the winter was about to bite. That week’s news was dominated by the killing of John Lennon three days earlier. Despite all this, the comic strip adaption of the 1930’s newspaper serial proved a hit with UK audiences and managed to make it to the top three spot for that year’s top box office hits despite being released in the last three weeks of 1980. It fared less well in the USA where plans for a sequel died after a disappointing opening weekend.

Now forty years later the film has a status that many other films from the time have still not and perhaps never will achieve. A cinema re-release this summer of StudioCanal’s 4k restoration of the film showed a brighter, sharper version that has ever been seen before.

My plan to write a book about the making of the film was a long process. After writing Harryhausen: The Lost Movies for Titan Books, in 2019. I planned to follow up with a book on the making of Flash Gordon. Wondering why no one had thought of making this before I was confident my publisher would say yes, and they did. What I didn’t expect was what followed. For years my publisher and many others had tried and failed to secure the rights to get a book about the making of the film published. I was warned by a friend who worked in as an attorney in Hollywood that the rights for the project were a hornet’s nest. For eight months, I worked with the various rights holders and along the way, uncovered another uncomfortable truth. Even if I can secure the rights to pen this making-of book, there are very few images that will help tell the story or convince readers it is worth shelling out £35.00. Why should this be, when it is a modern film with a larger production budget that any other film made that year?

On November 20th, my book will be published. A long and sometimes shocking search for images has come together with rare and missing behind the scenes photos and artwork. Such is the love for this film amongst the fans, from TV repeats and VHS viewings, the quotable lines of dialogue from the film have passed into school playground legend and now into the workplace and beyond. If you were about ten when the film came out, you would certainly remember it. From the glamorous and outrageously sexualised costume design to the camp dialogue and fast-paced action, the film has become a favourite at conventions and within the comic book communities. This year Brian Blessed revealed The Queen herself named it as her favourite film.

I searched the planet to track down the mega fans of Flash Gordon. They held the vital pieces of the film, from movie props to unpublished images and a series of stories which helped me build a picture of the production. I then turned to the surviving cast and crew members. I managed to access them all including those who had never gone on the record before. Each of them had either an exciting take on the production or had further contacts for me to chase. This became more like the making of a true-crime podcast series than a book about the making of a science fiction classic. Memories fade with time, and some of the accounts of the troubled production needed some clarity.

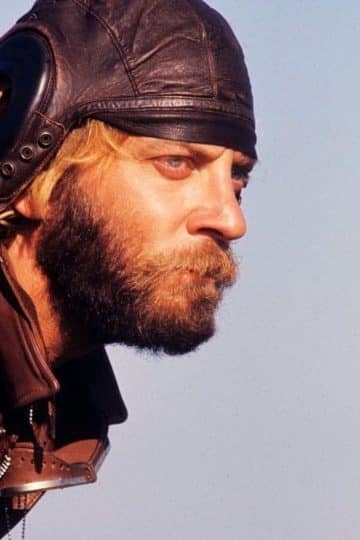

Sam Jones was in his early twenties when he was cast as the leading actor Flash Gordon. His fights with the producer led him to leave the film before filming was complete. Sam’s time on the production has gathered almost mythological status amongst fans. Sam was generous with his time and was eager to set the record straight. For a young man taking a leading role in one of the most expensive films in cinema history and relocating to London, it was quite a culture shock. Sam’s time on the film and his experience being Flash Gordon is a big part of what drew me to this project.

In the early 1980s, there was very little news about the behind the scenes struggles that filmmakers had. Most press at the time concentrated on the plot or the technical aspect of the production. Even these areas were shrouded in secrecy. Filmmakers didn’t want to give up their technical secrets as it might destroy the illusion they had spent millions of pounds creating.

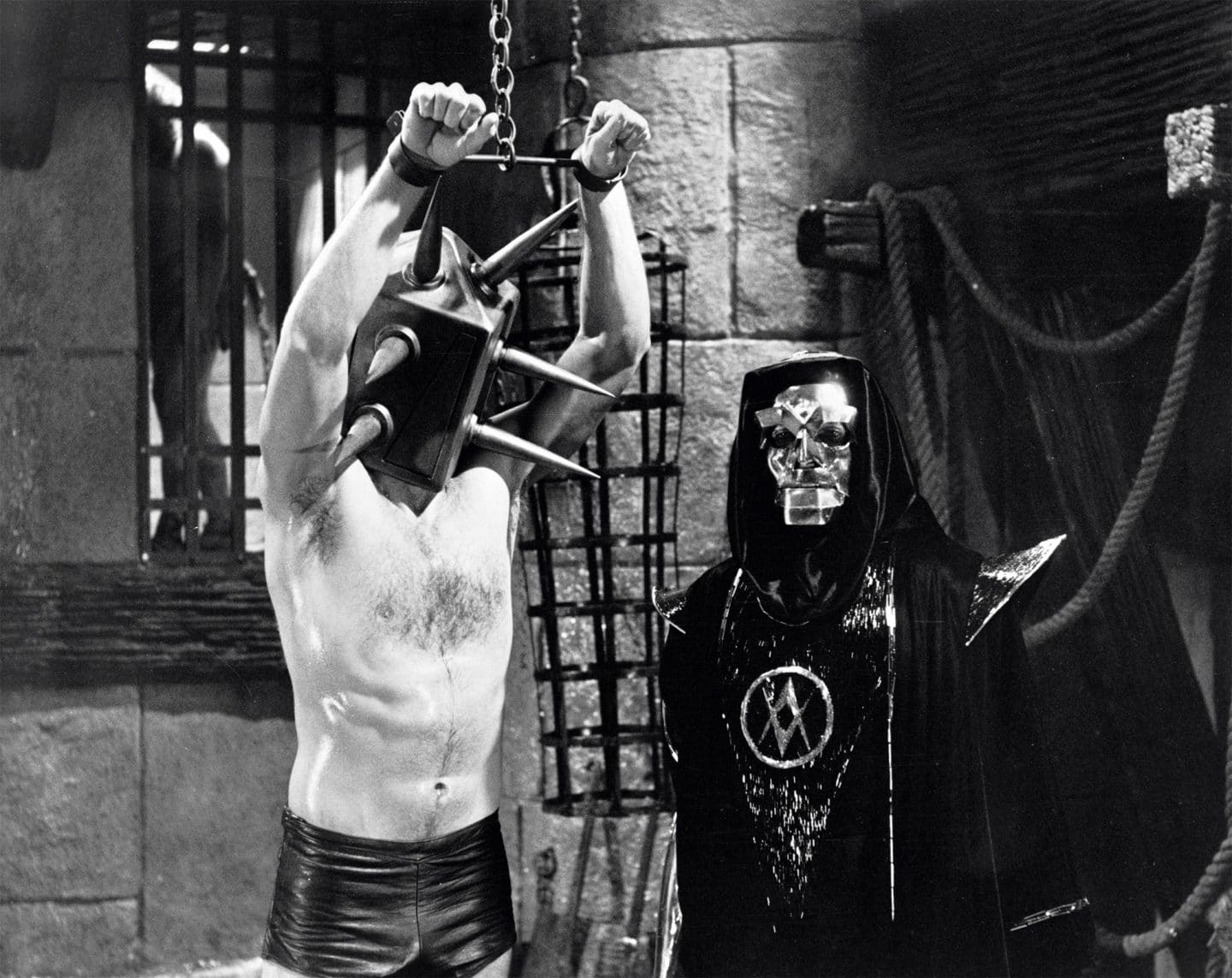

The budget for Flash Gordon was over $27million, three times the costs of the original Star Wars (1977). There was no shortage of talent, too, with the best special effects and creative teams available were gathered from around the globe. They would eventually descend on EMI Shepperton Film Studios taking over all of the major studio’s space. Such was the vast expanse of sets needed to create this unique cinematic version of the comic strip that the production even spilled out into an old aeroplane hangar in Weybridge Surrey. Today’s CGI-infused cinematic offerings from the superhero universes think nothing of flying a man or woman across the screen. For the photochemical technology of the late 1970s this was almost an impossibility to create effectively until Superman The Movie (1978) proved with it’s now iconic tag line. “You’ll believe a man can fly.”

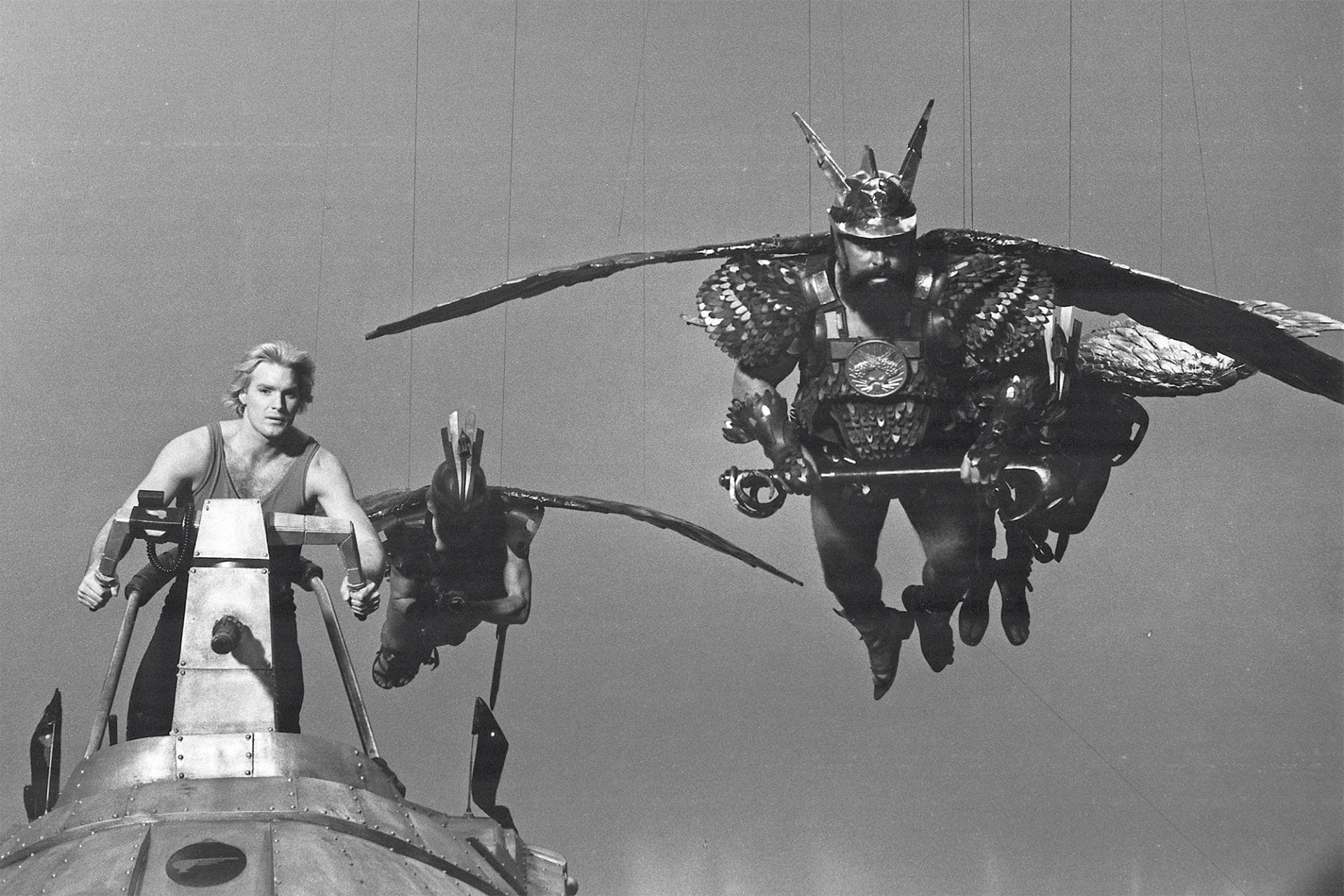

For the man of steel’s first outing, he only had himself to fly around with occasional date nights with Lois Lane in tow. For Flash Gordon director Mike Hodges needed hundreds of Hawkmen taking flight during the film’s cinematic climax. Superman had almost a year of planning and special effects experimentation which lead to a complicated front screen projection system what would tilt and zoom. This process was called Zoptic. Along with some traditional wire work, great editing and lighting, it was possible to wow audiences. Some of the most effectine flying sequences benefited from being covered with the cloak of night. No such luxury of was afforded to the Hawkmen who would have to fly in brightly coloured lit skies. The volume of shots needed and the tight shooting schedule of just seventeen weeks meant using a complicated system such as Zoptic was not an option for Mike Hodges.

The same was true of the spaceship models that were hurtling through the stars. Leading model makers Martin Bower and Bill Pearson gave me exclusive access to their photos from Flash Gordon with many never before published images showing deleted special effects sequences. Both men have credits on some of the biggest science fiction films of all time. Both had just come off Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979) when they took on the enormously complex task of creating the variety of different models in various scales and sizes for Flash Gordon. Some deleted scenes were shot and cut from the final print. These are in my new book along with new recently discovered photography showing the behind the scenes process.

Much came to light about the film that Flash Gordon could have been. The film’s legendary producer Dino De Laurentiis had prepared another version of Flash Gordon with a different director. Nicolas Roeg was best known for the thriller Don’t Look Now (1973) but it would be his unconventional science fiction film with David Bowie, The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), that would get Dino’s attention. Roeg worked on the first Flash Gordon film for over six months, but ultimately, he parted ways with Dino when both men realised they had very different ideas of how to bring this 1930s comic strip to the cinema screen. What is left behind are beautifully created pieces of production art that are being seen for the very first time in my new book. They reveal a grand vision that could not have been realised by the technology of the last 1970s. In many ways what Roeg had created was unfilmable at the time with any degree of realism that would meet the need for audiences already growing more sophisticated due to science fiction blockbusters Star Wars (1977), Close Encounters (1978) and Star Trek The Motion Picture (1979).

Dino’s plans to film three Flash Gordon films back to back reveals his epic vision as a producer. His 1976 King Kong remake was controversial but was also one of the biggest cinema hits of 1976. Dino was one of the last true Hollywood moguls. A man of singular vision who brought his creative European sensibilities to a world that is often portrayed as commercial and garish. Although he is no longer here to see the legacy of his work with Flash Gordon he does deserve much if not all of the credit for bringing us humour, colour and one of the greatest rock score soundtracks of all time with Queen. The following year he would next go on to make a star of Schwarzenegger with Conan The Barbarian.

Speaking with the cast, crew and director Mike Hodges the true story of how Flash Gordon took forty years to become an overnight success is finally here. Their memories of the filmmaking process and the amazing fans who kept the flame alive during the wilderness years of the late 1980s and 1990s has shaped the telling if this story. Today many film makers including the UK’s own Edgar Wright hail it as an all-time favourite. Flash Gordon can finally take its rightful place in film history.

Flash Gordon: The Official Story of the Film is out on Nov 20th – you can order it here.

John Walsh @walshbros October 2020

A podcast series accompanies this book here:

Trending

Masculinity 5 days ago

Sport 1 week ago

Health 1 week ago

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.