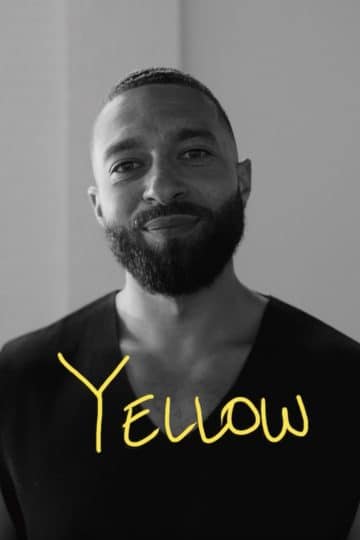

Romesh Ranganathan opens up about his mental health

Mental Health

Romesh Ranganathan on mental health, suicidal thoughts, his dad, the role of humour in tough times and why men need to open up - as told to the Under the Surface podcast

The Under the Surface podcast is a collaboration between Penguin and the Campaign Against Living Miserably in which top names from sport and entertainment speak to hosts Marvin Sordell and Adam Smith about their mental health in order to break the stigma. Romesh Rangathan is their latest guest and the comedian gave a particularly remarkable interview covering everything from his lowest mental health moments, his relationship with his dad and how men can get better at talking about these issues.

Here’s some of the key quotes from Romesh on the chat:

On his early years

My very early years were sort of pretty textbook. My dad was doing well, my mum and dad seemed fairly happy. I get nervous about describing my dad, because I love my dad a lot, but he was a bit of a loose cannon. He was a big drinker, a heavy smoker, liked the ladies – so he was a bit of a character. Most of my childhood was pretty happy but the only thing that I would say is that I would see a lot of arguments between my mum and dad about my dad’s behaviour and stuff like that.

Mum and dad had come over from Sri Lanka pretty young. My dad had come over for a job, my mum came over because she married my dad basically, she was 19 or 20 years old when she came over, a difficult thing for her to do.

My early years were pretty relaxed, we were doing alright and then my dad – unbeknownst to me or any of us really – had started messing up at work, started getting drunk quite a lot, and so he ended up either being asked to leave or being fired, I don’t know exactly what the details were. But he started trying to do other things, started to do deals and stuff like that, and was basically unable to keep up with the mortgage payments. We ended up in a situation where, almost as a complete surprise, the house got repossessed.

Then we were living in this house where my dad had managed to get or rent off a friend, and around that time it started to become clear that financially he was in a lot of trouble. I’m laughing about it now, but it was horrifying at the time. We’d get people that he owed money to coming to the door, and he’d be hiding under the table. People were banging on the door asking where he was and stuff like that, it was mad.

And then around that time, my mum discovered that my dad had been regularly seeing this other woman and I think the plan was that he was going to set up a life with this woman and leave my mum and us. So my mum found that out whilst we were living in this other house, and the real trigger point and the thing that really sticks in my mind and the high point of the chaos was when we hadn’t seen my dad for 2 or 3 days and my mum said to me; ‘ I don’t know where your dad is. What I’m going to do is drive you and your brother to this other woman’s house that he has been seeing and I want you to ask where your dad is. I can’t bring myself to talk to her, so I’m going to take you to this house.’

So me and my brother went to this woman’s house, knocked on the door and said ‘where’s my dad?’ She said that he was arrested two days ago, and it turns out that my dad had been involved in some sort of illegal import-export thing with a fraud element to it, and he was the subject of this police sting, got arrested in Leicester and he ended up spending two years in prison. During that time we couldn’t be in that house anymore, and the council didn’t have any more housing, so we ended up – me, my mum and my brother – living in this bed and breakfast for a good few months.

While my dad was inside we were in this B&B, then put into a council flat, then a council house. Then my dad came back out of prison and my mum and dad sort of reconciled. I’m doing a bit of a scatter-gun short history, but the long and short of it is that it was very calm and then every got turned upside down very quickly and our whole trajectory changed. My mum lost all her friends because she was in a certain type of group and everything went wrong. I didn’t know what was going on with my dad, and my dad went inside. We changed schools. It was just a big flip. It felt quite defining that period. I think that we would have ended up on a very different path had that all not happened. It affected me, my mum and my brother. I would hear my mum cry herself to sleep every night in the B&B living in the same room. She came over from Sri Lanka with her husband, she finds out that he’s been doing all sorts, the house gets taken away and I remember her – she was at rock bottom. I’d hear her crying herself to sleep every single night.

On telling nobody his dad’s situation

I think all of that stuff started to happen when I was about 11 and kind of carried on for the next few years, but it felt super quick, it felt like everything turned to crap pretty quickly.

I don’t remember feeling ‘this is horrible’, you’re just dealing with it as it happens. The sad thing is that the main concern was my friends not finding out what’s happened. That was my main concern, I just didn’t want anybody to know what was going on, I was just embarrassed about it to be honest. That was almost what I channelled all of my energy into, just didn’t want anybody to know that we were in a B&B, that my dad was in prison – I didn’t tell anybody.

The day my dad got put into prison, the next day was my birthday and I went out and had a birthday. Nobody knew, because I just didn’t want anybody to know. We went round to a mate’s house, watched some films, had a bit of a party – it was so weird because I knew my dad was about to spend two years in prison. I remember sitting with it, being conscious of it that I don’t want anybody here to find out.

On having no home and no food

We didn’t have any money for food when we were in the B&B. We had a microwave under the table in the B&B and we lived off microwaveable cheese sandwiches. That was our stable diet. Now I’m vegan and I find cheese morally reprehensible! If ever I see a melted cheese sandwich ever again, the nostalgia reminds me of that B&B – it’s so vivid.

The other thing, I know this sounds like such a cliché, but if ever I’m on holiday, you just have a moment that you can’t believe your luck that you’re alright. You don’t have ambition at that stage, any aspirations, not thinking about hopes for the future, just thinking I need to get through this – all you’re thinking about is survival, how do I get through the next week? You’re not thinking about what does this mean for my options moving forward, what am I going to end up doing what I grow up – you don’t care about any of that, you’re just thinking about how am I going to end up getting through this.

I went within myself, I became almost nude. I became really quiet, I didn’t chat very much to the point where people became concerned.

On confronting his dad

I remember when my dad had just come out of prison, I had just done A-levels and I was off to uni, and it was the specific moment where I had come back from a night out. I’d come back to Crawley after a night out with some mates, and just done a typical bloke-of-that-age type of thing not letting my parents know when I was going to be back and came in drunk or whatever. And my dad said to me, ‘What are you doing? You’re being so inconsiderate’, and then I just completely unloaded on him. I just turned to him; ‘The idea that you can tell me what to do and you can come and parent me and tell me that I’m being inconsiderate’, and just monologued at him. And he just took it. He sat there and took it.

Sri Lankan culture is that you respect your parents, and really I was out of turn to be honest with you. My dad didn’t have a temper with us, but he was pretty front-footed, and I’m sure in any other circumstance my dad would have said something – he didn’t say anything. He sat there in complete silence and just took it. And then I walked out of the house, walked off, did the dramatic slam the door – slam it again to make sure everybody heard it – and then just wandered off for a bit. But I think it was the horrible thing where I’d said the things he’d thought of, I didn’t say anything that wasn’t true, but I guess that was the first time that I’d sort of ever expressed to him how I felt about his actions.

A lot of that was coloured by the fact that I’m his son and feeling that sense of rejection, and some of it may have seemed unfair, but that was the first time we’d had a conversation – I say conversation, it was a one-sided conversation. The first time we’d ever really talked (about it).

On his lowest point

When my dad went to prison it was around the time that I was doing my GCSEs and I sort of stopped caring about school and exams, and went on to do A-levels but I was bunking off, not really applying myself and smoking a lot of weed and I just wasn’t into it at all. I just didn’t really care, and I wasn’t invested in my future at all. Then I had a bit of a realisation, didn’t do very well in my A-levels because I didn’t do any work at all but thought I’d probably be alright. I think around the time of my A-level I just got back to the thought of what am I going to do with my life or what are my options going to be.

I remember around the time of getting my A-level results, I very seriously thought about ending my life, because I just felt I’d been through the sh*t – or we’d been through the sh*t – I didn’t see a bright future. And then I got these A-level results – which I deserved because I hadn’t done any work. I don’t know what I was expecting, because I hadn’t applied myself at all, but for some reason I thought some miracle, I wanted something good. And then when I got those results, I know it sounds so crazy, I just thought it was another sign that nothing good was going to come to me.

So when I go to uni, I wasn’t applying myself, I was just turning up and just doing whatever – I went through period of thinking I should do some work, but I wasn’t going to lectures. The people I was around were working and that made me work a little bit.

But I remember coming home from uni and I’d saved up – I’d always been really into my music – and I bought this little hi-fi unit, but I didn’t wanna take it to university because you can’t trust people. So I left it at home and we had this guy who was staying round, this Sri Lankan friend of my parents who was struggling and so they said you can stay with us until you find your feet, and he was staying in my bedroom. And I remember coming home and they had moved my hi-fi because he needed to put some stuff down or whatever, and I flipped out – I didn’t flip out and get angry, but I was really upset that this thing had been moved. ‘I’m not even welcome in my own house, why has my stuff been moved’, and I realised after that this was a massive overreaction and why have I have overreacted like that? It wasn’t a rational reaction to what had happened, and that was the moment where I thought that I need to figure out what’s going on in my head, that was the first time. The next week at uni I saw that you could get counselling and therapy at uni, so I signed myself up and started doing sessions from there really.

On advice for others in dealing with suicidal thoughts

You know the truth is, what I found in my personal experience, and it’s happened again since then, when I thought about taking my life, what happens is the old cliché, that it’s a permanent solution to a temporary problem. I remember the reason I found it so enjoyable to think about – I’d fantasise about it – I’d fanatisise about a time when I didn’t feel like this and taking my life felt like a way to access that. It felt like the way to achieve that. So I would think about it, and would think about if I was gone, immediately a weight was lifted off my shoulders, I don’t have these problems anymore. It’s tempting. In those moments, there’s no getting around it – it feels tempting. It feels like a really instant way of making this go away.

What I found is that you just have to do the thing that you don’t want to do – you have to talk to somebody or just seek some help. Because what then happens is you look back on that time and think you can’t believe you came close to doing that. You look back and you can’t believe it. You have to, even through you don’t want to, you have to know that you’ll feel better as a result of doing it. Even though it doesn’t feel like it in the instant, you don’t wanna do it but you know you’ll feel better as a result. I think it’s so difficult to get yourself to that point, because you feel embarrassed.

You look at that on paper – Romesh thinks about ending his life after A-level results – it’s like what?! Even at that moment at my lowest I was still privileged, I was doing A-levels, I was receiving a free education, I was housed, I had enough to eat. There are all these things where I wasn’t anywhere near rock bottom, but mentally I was. You don’t know what someone is going through. It feels when you’re in those moments, it feels so tempting. The truth is that you’ve got to understand that you will not feel like that forever. By talking to somebody you get an access to try and uncover how you get out of feeling like that.

On starting therapy

What happened was that I was just sat there going ‘I am messed up man, what the hell do I do?’ I didn’t want to talk to my girlfriend about it, I didn’t want to talk to my friends about it and I certainly didn’t want to talk to my mum and dad about it, so you just think what the hell am I going to do then?

So you see this thing and I didn’t know if it was going to work, you don’t just think oh that’s the answer, but that was something, let me try that. I could have gone to one and said this isn’t for me but it so happened that I went to that first session and I thought I should probably carry on.

It just wasn’t as smooth as that, I was just desperate and I needed to do something and I couldn’t talk to anybody around me, so let me go and talk to somebody else – that’s what happened. What would have happened if I didn’t find that counselling or therapy useful? I don’t know what would have happened? I didn’t know the next thing, I just tried it and it was helpful. I say helpful, didn’t come out, put that in a box and I was good to go, I have gone on to spend many, many years dipping in and out of therapy, and having dark moments. That was a low point, I’ve had many low points since. Some of those have been when, externally, everything looks great. You can’t predict when that is going to hit you.

On keeping therapy a secret

The honest truth is that I kept it a secret, and I didn’t tell anybody – I think I said I was going to the gym, but then after I’d been doing it for a few weeks and they’d noticed no discernible change in my body shape, I think people started to become suspicious.

The honest truth is that in Sri Lankan culture – I just couldn’t have told my mum that I was doing that, ‘I’m going to a therapist’ – there’s a stigma attached to that in terms of people see mental health as a misnomer, they think it’s not your health as your health is your body, what’s mental health? So saying to people that I’m going to a therapist, I just didn’t feel like I could tell people.

Now, even men talking about their feelings is something that we’ve made so much progress, and recognising mental health as something that needs to be recognised and acknowledged, and if you’re struggling with it you can be open and say. We’ve made so much progress with that over the last 10-20 years, we are worlds apart. Getting to a point where someone can say to a friend that they’re struggling in their head at the moment, not that long ago that’s not something that you’d feel comfortable saying to somebody.

On getting into comedy by accident

I really loved teaching and I did teaching for a long time, I became a head of sixth form and really did find that job rewarding, and then I sort of fell into comedy by accident. I was gigging in the evenings after school, so I’d finish school, jump in the car and head off to a club or wherever and trying to make my way through it. And then it eventually got the point where someone said to me that I could do this as a career and so from then on, I started thinking about what might happen there. I didn’t have any aspirations or anything like that, I just thought let me see if I can be a comedian. But I loved teaching so I thought if this doesn’t work out, I’ll spend the rest of my life as a teacher, I’ll be happy with that.

The truth is that if you have mental health issues, you’re going to have that whatever you do, whatever job you chose to do. I really loved teaching and I really loved comedy, so I felt that I’d do things that I really love. Part of the reason that I was pushed towards that is that I saw my dad driven almost purely towards financial gain, and I saw what that did to him, so I thought I’m not going to worry about that and actually do stuff that I want to do and the finance can be a secondary target for me. Let me just do what I wanna do and see what happens.

On Social Media and it’s perils

I think being a comedian or a public figure, I think you do have to be mentally robust to be under that scrutiny. I personally think that footballers have got the scrutiny worse than anyone else. You mentioned social media earlier, and this whole obsession with presenting positive outlook – I really would like a culture where people start posting up about where things have gone sh*t. I do think this whole thing about putting out a positive thing of where your life is at, I’m not convinced that’s entirely useful. I get why you do it – I’ve done it!

But at the same time, I do think this idea of getting around that and getting to a thing where we are actually being a bit more real about what’s going on. I don’t think there’s anything nicer that someone you really respect saying they’ve had a dreadful day or something has gone wrong. I love posting about how I’ve absolutely died on my arse at a gig!

I remember when I first did Russel Howard’s Good News, it was my first big tv slot and I didn’t watch it because I never watch anything I do. But I was sitting in front of the tv watching something else – my wife didn’t want to watch it either – and the set went out and on Twitter I just saw that’s really good, who is this guy, haven’t heard of this guy and I think oh, that’s cool and then suddenly I got this is the worst thing I’ve ever seen, why have they got this guy on and I was like Oh My God – it was my first realisation that you can get negative stuff come off of this.

On Social Media Daily Hate

I would say every day, I’m not exaggerating, I would get every day someone tell me they hate me on social media. Definitely at least one, saying why can’t you disappear off tv or whatever, and I think you just have to desensitise yourself to it. Desensitise yourself to that, but also to people saying that you’re really good. People come to my show and say that’s the best comedy set I’ve ever seen, and I just think you need to watch more comedy! There’s absolutely no way that’s the best comedy show…

Being in the public eye, I came off Twitter two years ago as I just found it poisonous. I don’t think it’s good for you to know what people think about you, positive or negative. I don’t think that being a direct stream to your brain is good.

On his first Apollo show being ruined

I would love it if my job was making a show and it just got put in a vault somewhere. When it comes out, that’s the most anxious I am because you think I’ve put so much into this and now people are gonna judge it, and some people are gonna say this is awful, and that’s really hard. You read all the good comments and think they don’t know what they’re talking about, but you read one negative comments and you think that must be a comedy expert!

We have this thing called comedian’s eye where if you’re doing a gig but one person isn’t laughing, that’s the only person you can see. It’s just this thing that you can help, but the truth is that you can’t do anything about it. If they don’t find me funny, I can’t break-dance, this is the act. You just get used to it.

My job isn’t to get everyone to like me. I don’t wanna be so vanilla that everyone likes me. I had two examples of gigs where I had completely different responses. I was doing The Apollo, my first run of shows at The Apollo, proper dream come true ‘Oh My God my show is at the Apollo’ venue. Like an idiot in the interval, I looked on Twitter. In the interval. So stupid. So incredibly stupid. Somebody goes ‘At the Romesh Ranga show. Hate it’. I deserved that – I shouldn’t have looked.

I go out and do the second half, I’m not even in my body, because of that comment. I go out and do the second half, and bear in mind I’ve wanted to do The Apollo for however long and I’m doing a run of shows, I should be absolutely buzzing. One comment – second half ruined. I’m doing the show, and in my head it’s that guy hates you, there’s probably a few other people like that, you need to start improving, you don’t deserve to be here.

I do the rest of the show, come off, my agent is there, a few mates – I can’t even hear them because I’m out of it. It was a bar afterwards, and I walked in and I was just out of it, it ruined it for me. It took me until the next day to just rationalise that.

The tour after that, I was doing a show up in Edinburgh. It was a great show, went really well and after the show I looked on social media and loads of nice comments and one guy said ‘Hated it, left at the interval’. But the difference is that I knew that was a great show, could tell by the audience response. I knew that I’d had a good one so it didn’t have any effect, and I remember thinking that felt like a good thing – I went from absolutely spiralling to just being ‘okay, not for everyone’. I’ve still got the ticket money, you don’t get a refund because you don’t like it!

On wanting to quit comedy

So I thought okay I need to quit my teaching job and handed in my notice and then three days before I finished teaching, my dad passed away of a heart attack suddenly. So we had to deal with that, turned out my dad’s finances were a hassle. So the first period of me being a full-time comedian, I just wasn’t in the game. I was trying to figure out what to do about that. I no longer had a teaching salary coming in.

There’s a lot to process there because I plunged my wife and I into a real struggle and not for a noble reason. I was doing alright as a teacher and I’ve gone ‘I think my job should be getting paid to say what I think’, such a selfish, narcissistic thing to do. And as a result of that, we’re in trouble. As somebody who is trying to do the right thing by my family, I struggled with that to be honest. It was a difficult thing. The number of times I’ve thought about giving up comedy. So many times. So many times.

I remember I was doing this comedy competition and I’d done a corporate gig the night before, I think in Glasgow, and then taking a train to Leicester to do this competition. We were struggling, our car had been impounded, we were struggling to pay the bills, and I remember phoning my wife and saying that I don’t want to keep doing this anymore, I can’t keep doing this, I don’t know why I’m going to this competition and why I’m doing any of this.

And she said ‘Why don’t you go and do the competition, and then come home and let’s have a chat about it’, and I said okay. So I got the train down to Leicester for the competition and then was going to go home and have a serious think about what I’m gonna do because this is awful. I loved doing comedy, but I didn’t love doing comedy so much that I was willing to put my family at risk for it – which I already had done to be fair.

Then I won the competition, I don’t know if it’s because I felt liberated by thinking I’m just gonna go and be a maths teacher after this or whatever, and it just gave me another 6 months. I phoned my wife after and she said ‘Let’s just see, give it a few months. You can go part-time’, but I did go to that gig thinking I was gonna quit that night, that it was gonna be my last gig. Well my last gig at trying to be a comedian.

On using humour as a coping mechanism after his dad’s death

My personal feeling is that comedians are just wired slightly differently or something has happened that has changed their way of looking at things, because that is the job of a comedian I guess, to look at things in a way that other people might not look at them.

Everybody to some degree uses humour as a coping mechanism, I think that’s fair to say, and I do it all the time. I grew up getting bullied because of my lazy eye, and now it’s one of the things that I joke about the most. You almost wanna get there first, so you can’t say what I’ve already said about this.

But sometimes you can use humour to deflect and that’s something to be aware of. I think it can be really useful. I have a very dark sense of humour, and my family have a very dark sense of humour. For example, when my dad passed away, my brother came home and found my dad collapsed after he had a heart attack and passed away. I turned up and immediately started crying and the next day we were round at my mum’s house and dealing with the aftermath of that and people coming round.

My brother subjected me to a 10 minutes roast about the sounds I make when I cry. And we were properly laughing about it. He goes ‘Listen man, we’ve got to talk about some of the sounds that you were making, it was mad! I’ve never heard noises like that come out of a person!’, and we just started laughing about it. And I know it sounds super dark, but that almost felt cathartic. We were going through this horrible thing, but you can still find light in it and we can still joke.

Also equally, I talk about my mental health on stage and you can talk about all things – race, homophobia, or whatever you wanna talk about – but by making jokes about it, you can bring it into the conversation. I talk about mental health very openly in my stand-up, and I do it because I have funny things to say about it, not any other reason. But the hope is that but normalising chatting about it, the staple of getting a prostate exam has been a staple of comedians for so many years, why is going and having therapy not a staple of stand-up? It’s something we should be talking about just as openly and readily.

I think that there’s a double-edged sword to it. I think that in some ways humour is a great coping mechanism, but in other ways is someone using humour as a coping mechanism because there’s something going on and something to be aware of.

On still wanting to message his dad

My dad passed away three days before I went full-time in comedy, so one of the things I always feel sad about is that my dad never saw me become a comedian really. It was really hard. I remember on one occasion, my dad was aa a proper hardcore Arsenal fan, and I remember we were going in for a player and I pulled my phone out and went to text him to go ‘what do you think about…’, and then I remembered that he’d passed away, because I always used to chat to him about Arsenal.

Grief is tricky because you have this idea of what grief looks like, but it’s different to everyone. To be honest with you, one of the things that I’m going through with my dad, is that I haven’t thought about him in a while, where your life carries on. In the last few years I’ve started to forget what he sounds like.

On losing his best friend in teaching to suicide

Some people are really, really good at making it seem as though they’re okay because that’s what they feel like they need to do. So that’s what Mark felt he needed to do, was project this thing. And it’s heart-breaking to me that aa really close friend was going through all of this stuff, and he came to dinner with me and we were joking around and stuff. Obviously in the right circumstance that is the right thing to do, but I didn’t know the context of it and what he was going through. That is one of the reasons that I felt I wanted to do something.

The truth is selfishly you look at what you could have done – could I have done more for him? Could I have reached out to him? And the answer is probably yes. I thought to myself if I can do anything to help encourage people like that to reach out, and look out for everybody, touch base with people and ask if they’re alright. It’s not a functional conversation starter; you’re actually asking if that person is alright. Looking for signs that people aren’t alright. All of those things, we’ve gotten to a point where that is being done more regularly, and that is in a better place and that’s the reason that I got involved with CALM really.

Men open up individually, not collectively

I think individual men have become better at talking about their feelings, and receiving people talking about their feelings. My friends as individuals are great to talk to; my friends as a group it’s just different vibes. Groups of men, we still have this thing where your conversations just can’t be about that. I think it’s getting better but it’s much better if you’ve got a problem, I know that any one of my individual friends I can have a chat with and open up to and they’ll be receptive and responsive, but if I’m out at the pub with a group of male friends at a pub, to start that conversation about how are you really feeling, I don’t think that even with as much progress as we’ve made, that is something that we haven’t got to yet.

I think that the culture is talking about superficial stuff. Part of the culture of blokes is to just rip each-other to shreds, it’s the direct opposite. How can you have this thing where you say you’ve not been feeling alright, ‘Oh my God, have you heard this bloke!? Everyone pile in!’, that’s the thing. I’ve suffered 40minutes of negative banter because I went to the toilet too frequently the last time with a group of mates. You think I’m gonna suddenly start opening up? I think that is a bit of a cultural thing. Men have become better at opening up, but I think groups of men I still think there’s an issue there.

I think the truth is that you have to accept that there’s not going to be an immediate fix to that. I think that younger generations – my eldest son is a teenager now and they still have that ribbing each-other, but I do think he’s more aware of the concept of mental health than I was at his age, and that’s something that’s only going to improve as time goes on. But you think about the progress we have made with men talking about mental health, I don’t think it’s something that gets sorted out immediately but it’s a cultural shift where it is something that gradually the expectations get changed.

There are certain things that blokes would say in conversation now, and quite rightly you’d pull him up for it, and that’s a cultural thing where people have been made to be more aware of how they should be conducting themselves. I think if you have a situation where people are aware that this is something that people go through and this is something that we should be talking about, then gradually I think you’ll start to see that change, but it won’t be tomorrow.

Romesh was speaking about his mental health struggles on the Original Penguin X Campaign Against Living Miserably Under The Surface Podcast

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.