“Discipline is about choosing between what you want now and what you want most.”

Fitness

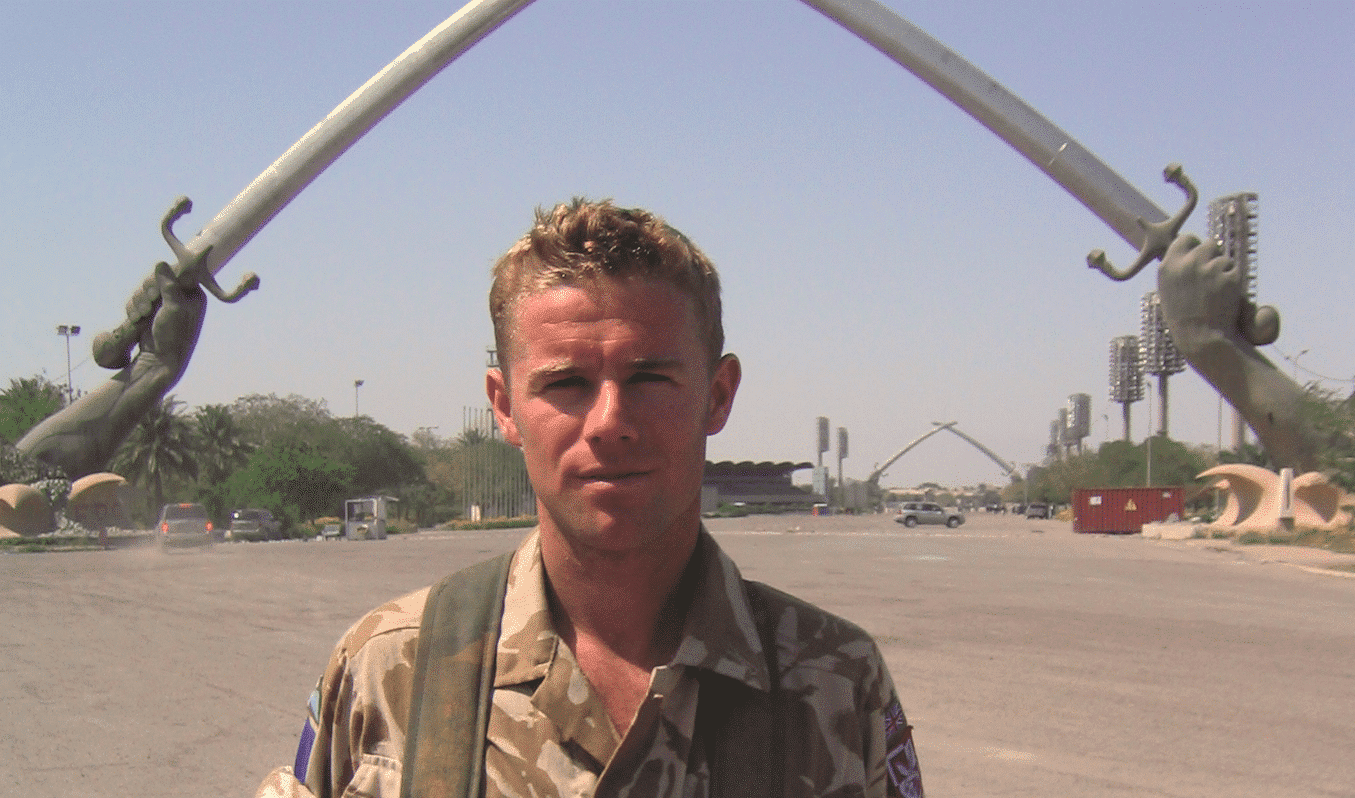

Sam McGrath, former PARA and now businessman and dad of four, chats to The Book of Man about his new book, and mental fitness...

Sam McGrath was one of the youngest soldiers since World War II to achieve the rank of major and ran the selection course for the crack Parachute Regiment for three years. He left the military to enter the world of business and is now Managing Director of a FTSE 100 company in Singapore. Here’s how the core values he learnt as a Para enable him to juggle that demanding role with being a father of four, and an elite endurance athlete….

What was your background and why did you join the Paras?

I was 15 and had my first session with our school’s careers counsellor, who, unsurprisingly, asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up. I said a spy, a stunt man or a Ferrari salesmen – which to be honest all still appeal! He paused, looked at me, and said ‘in 25 years you’re the first person to say any of those, but here’s my professional advice… There’s no Ferrari dealer in Preston, so that’s a ridiculous idea, but what about the Paras? They jump behind enemy lines like spies, do fun dangerous stuff like stuntmen, and they wear Ferrari-red berets.’ Suffice to say, he not only set me on the path to join the Paras, but for my first sales job too…

You were among the first soldiers to enter Kabul in the aftermath of 9/11. What that was like?

As a soldier it was the perfect mix of exciting and intimidating – we didn’t know how we would fare, when every army in history had failed to bring peace to Afghanistan. As an observer of human dynamics it was an invaluable lesson in managing expectations – we judged our success on whether we could rid the Afghan people of their tyrannical rulers and preserve law & order, but the Afghan people wanted Western-style infrastructure, not just ideologies, and in short order. I left Afghanistan awestruck by the beauty of the country and the hardiness of its people, but above all with an appreciation that prosperity was the route to peace in the region.

What was your life like and how did you keep morale up?

I can’t imagine a better way to spend my ’20s. We believed in each other and what we were doing. Morale was rarely an issue – if we weren’t on patrol we were either pushing each other in a makeshift gym or through aggressive banter – we laughed like children every single day.

I will spare you the war stories, but I’m often asked if I suffer from PTSD and the short answer is ‘I don’t think so’ – but the truth is more nuanced. Despite being shot at, bombed, and losing more friends than I care to remember – the biggest mental baggage I carry is a sense of belonging. The intensity of operations brings out the best in the Paras, and there’s not a day I don’t miss the community, identity, and purpose of serving in a tribe of paratroopers. Having read broadly about PTSD, I’ve learnt that the activity that psychologically best prepares warriors for combat is the same one that helps them deal with the consequences of it: demanding physical training. Hence ‘being Para fit’ as a corporate warrior is the best preventative medicine for PTSD, and I prioritise it like any important meeting.

You ended up running PE training for the Paras. Just how rigorous is it?

The first thing I’d say is confusing Para selection with ‘PE’ is akin to confusing Ice Cube with Jack Frost – i.e. you’re ignoring its very essence, an air of intimidation, uncertainty, grit and focused aggression. In isolation each component of Para selection is within the grasp of a dedicated club runner with a passion for cross-fit, but in aggregate it’s a far tougher test.

By far the most difficult aspect of Para selection is mental. We use a combination of uncertainty – not knowing what’s coming next and whether your performance is making the grade – along with some brutal tests, like the log race, stretcher race and milling, to help our soldiers really explore the perimeters of their psychology. Having led the selection for two years, I was frequently surprised at my inability to predict on Day 1 who would pass. But what I’m certain of is that there’s absolutely no correlation to biceps. The best analogy I can think of is MMA: how many times do you see a ripped Adonis getting a very public lesson in humility from a podgy past master? The Venn diagram of performance and appearance often overlaps, but ultimately it’s your mental operating system that determines success. I eventually took great comfort from my inability to predict success. First, it justified the requirement for a formal selection process, and second it proved our process was objective, performance-based and immune to bias.

“Para selection is about grit and optimism”

You talk about the Para mindset – how does it give you confidence to push forward when you think ‘I can’t go on’?

The Para mindset has three ingredients; optimism, grit and a growth mindset. Our selection process has been refined over 75 years so that it implants far more than it isolates these critical Para characteristics, so our people don’t just survive but thrive in hardship and uncertainty.

There’s not a person that starts Para selection certain that they will pass it. So from the outset they need to overcome the mental pressure of public failure and assess whether the prize is worth the potential price – they need to be optimistic. Throughout the course we put them under conditions of stress, for instance fighting someone of equal size and weight in front of their peer group, and not being allowed to duck or defend themselves – they need to have grit. The course involves progressively more difficult tasks, which call on more mental and physical resources than the activities that proceeded them – they need to have a growth mindset to believe that they’re capable of doing more with a tired body on Day 20 than they were when fresh on Day 1.

People often misunderstand elite selection processes as tools to preserve an elite status – but the important thing is the individual mindset they foster, and the compounding effect of having 100 of these people linking arms to tackle some of our nation’s most daunting tasks. By pushing our soldiers on Para selection beyond their own appetite for challenge, we bulldoze their limiting beliefs on what’s possible and build a mindset that lives up to our regimental motto – ‘ready for anything’.

What was the highlight of your time with the Paras, and why did you decide to move on?

Looking back, the highlight wasn’t any single event, it was being surrounded by a group of people I loved, who were completely vested in each other’s success and felt ready to charge at hell carrying a pail of water – if that’s what we needed to do. As for moving on, I’d scratched every itch. I’d been on multiple tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, commanded big groups, been through difficult times, and in 2010 the military was transitioning from a war to a peace footing. I wanted kids and to settle down, and I felt young enough to start again, so I did.

How was the transition from battlefield to boardroom? What was the biggest adjustment you had to make when working alongside civilians as opposed to soldiers?

The biggest challenge of leaving the military was cultural. In the Paras your first instinct is to trust everyone – in a corporate setting, many believe and act as if the opposite is true. Team is a verb in the military, but too often just a noun in the private sector. In the Paras money was of no interest to anyone, but in a commercial environment it’s all too often the motivator and the metric for everything.

What Para skills/techniques/mindsets have you applied to great effect in business?

Many things stand out, but above all it’s the process of mission analysis, which is essentially a planning framework to identify what’s the most important mission, the critical steps necessary to achieve it, and then how to manage scarce resources effectively to best guarantee success.

You’re a keen ultra–marathon runner. Is it more about mental endurance than physical ability?

I think just like Para selection, the success equation for ultra-marathons is heavily skewed towards mental, not physical resilience. At some point in every race you start to rationalize how giving up is the most responsible thing to do in order to fight another day – but personally I have come to love pushing through this dialogue and then laughing about it at the finish line. I find the easiest way to navigate this is to anticipate it and have an answer for it. The one that works best for me is promising before the race to give my finisher’s medal to one of my daughters – and I don’t want to have that conversation… Being a positive role model to my daughters is critical to me. I hope seeing me push myself in training and competition will inspire my girls to prioritize fitness as they grow older. Hence me giving up in competition is akin to me giving up on that goal.

That said, it’s easy to think everything happens on race day. I believe my ultra-marathon success has been won in training, not in competition. Moreover, the complexity has not been any technical aspect of my training, but the building of a personal ‘battle rhythm’ to relieve the frictions of an overburdened schedule. I think aligning everything I do with my top goals and securing time to train has ultimately been more impactful than any inspiring self-talk or promise to my girls.

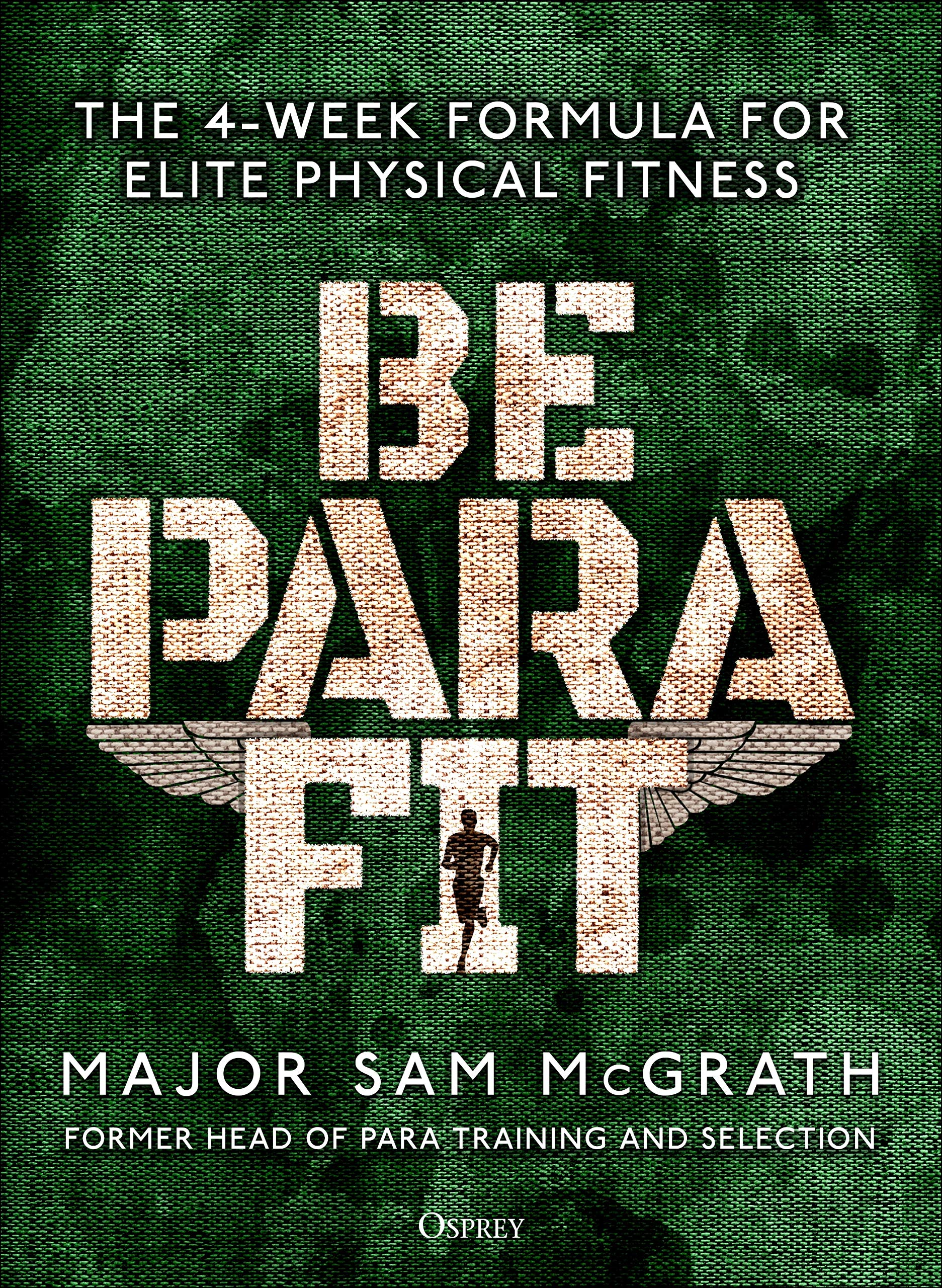

Your new book, Be PARA Fit, works for any fitness level – the secret being your holistic approach. What are the elements that link together to supercharge success?

A critical element is a systems approach to training: prioritizing sleep, nutrition and mobility instead of focusing on fitness activity in isolation, to accelerate progress and build sustainable health foundations. Another key part is using a drills-based training methodology to quickly embed the correct technique, making fitness acquisition quicker and easier, and reducing the risk of training injuries.

“My daughters are my motivation”

However, I think the most compelling element is that it’s both practical and weathered in my own personal experience. Other fitness books and programmes are written by people who work in a gym all day, with little understanding of complexity, of balancing sedentary office-based work, busy family commitments, and training. They tackle the easy part, describing how to perform a particular exercise, but fail to solve the most difficult problem in achieving fitness – finding and maximizing available training time. In contrast, I combine both a fundamental understanding of fitness training with my current experience of balancing an elite-level training regime alongside a big job, my family, and a time-consuming writing hobby.

You say that ‘processed carbs should be treated like recreational drugs’ – why?

Because however good the experience of consuming them may be, they’re shit for you. Real people, committed to real goals, require real food. It’s impossible to train your way out of a poor diet and nothing will cannibalize your training progress more than fuelling your body like you’re at the cinema, when you want to be at Kona.

The book contains lots of motivational quotes from leaders and thinkers. What’s your favourite?

Without any doubt Abe Lincoln: ‘Discipline is choosing between what you want now and what you the most.’ I think it’s the perfect maxim for leading a fulfilled life; covering everything from fitness, parenting, relationships to professional success.

Finally, you’re a proud dad of four daughters – what’s the best and worst things about being a dad? Do you treat it like a mission sometimes?

I love the chaos of a noisy house, but above all I love seeing my girls developing passions for music, sport and playing – I’m at my happiest on our trampoline with all four girls played anti-socially loud. My least favourite is watching them metaphorically fall over and graze their knee and having to step back so that they pick themselves up, when my bias is to bound over and smother them with love. But I’m clear that if I’m to raise four girls who thrive independently, loud music and love might get them to the starting pistol but not to the finish line. They need a mindset that’s ready for anything, which is the mission me and Annie (my wife) are committed to.

Be PARA Fit: The 4-Week Formula for Elite Physical Fitness by Major Sam McGrath is published 23 January (Osprey, £14.99).

All author royalties are donated to The Parachute Regiment’s charity: Support Our Paras.

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.