Ultra-Hero for Mental Health

Fitness

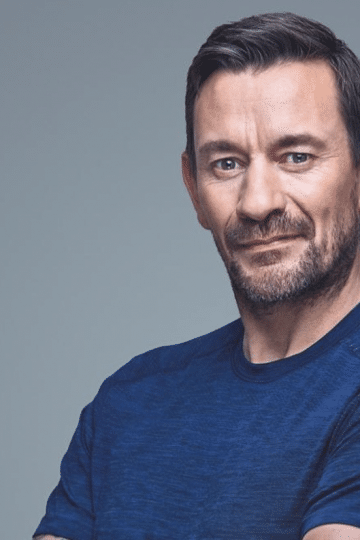

Matt Bagwell is taking on 21 ultramarathons across all 43 borders of England to bring people together, and raise money, in the name of mental health.

Run The Country Ultra is a fitness challenge with a difference, for it is a prime example of how one man can come back from the darkest of places to find a new positive path in life and inspire others too. That man is Matt Bagwell, a former business leader and now performance coach and mentor…and endurance athlete. For Matt is currently in the midst of running 21 ultramarathons across all 43 borders of England. He’s doing it in partnership with and to raise money for the Campaign Against Living Miserably and is putting mental health at the forefront of this challenge. As you’ll see in our interview with Matt below, he is someone who has hit the lows and knows the value in communicating the issues, as well as seeking ways to help people maintain good mental health. Before you read the interview, conducted before he embarked on the ultra-marathons, check out Matt’s progress on his Instagram page below:

Can you tell us about the challenge Matt?

So from September 5th to Friday October 1st I will run 21 ultra mountains across all of the 43 borders of England. A marathon distance is 42.2k and anything beyond that constitutes an ultra marathon. So some of them will be just a few feet over a marathon, some will be about 58 kilometres. And I will run 21 of them, which is an equivalent distance of Land’s End to John o’Groats, and longer than it as the crow flies. Climbing more vertical gain than Everest. By any measure, it’s a really long way. It’s the cumulative fatigue that’s put onto the body and mind that’s what makes it extraordinary. It’s not the furthest anyone’s ever run, it’s not the fastest, but it’s definitely mine and I’ve got to do it.

There’s two objectives: the first is to be an exemplar for how it’s possible for somebody to completely U-turn from a path of depression and planned suicide, to just living and then doing something extraordinary, while maintaining positive mental health.

The other thing is to raise money for when people are in a crisis situation with the Campaign Against Living Miserably.

Also for me it’s about bringing communities together around the conversation of what people can do to recover from or completely avoid negative mental health experiences. It’s to create a lighthouse, really, to do something extraordinary to prove that it is possible, and to get people involved in that, to learn the tools, including running, that people can use to enjoy positive mental health.

What kind of ways can people get involved?

I’ve already done some anticipation events where people who have never run before can learn to run. It’s a little bit like couch to 5k, but it’s a much more slow, progressive process. The last cohort have just graduated, at a 88 per cent success rate, which is much more successful than others, because it’s slow and progressive. I’ve also raised quite a bit of money with virtual running events. But people can also get involved in the run and join me for 5,10,15 km, whatever they want. I don’t intend to run alone. When I did my test runs, people spontaneously turned up to run alongside. I think they’re not running because they necessarily know me, they’re running because they feel some solidarity for the idea.

And how were you bearing up in those tests?

I ran 300k in that week, I’ve never run that before. It is everything that I expected it to be. It is a test of physical resilience. It’s a logistical conundrum, you’ve got to move from place to place, you’ve got to stop for refuelling for the following day, the day that you’re actually still running. You can’t see any one run in isolation. You’ve got to see them as a string of events. And there’s lots of navigation. When I run around Brighton I know exactly where I am, and I’m just running. When you’re running through fields in Bishop’s Stortford to Cambridge, for example – that was my lowest point – where farmers have determined that they don’t want to keep public pathways open, or they’ve planted and ploughed a field that you’re meant to be able to run through, it’s a lot of stopping and starting, and it’s mentally fatiguing.

I think inevitably there’ll be some tears, probably mine. Certainly the crew’s. Because it’s going to be arduous. But I think that that’s inevitable. What I’ve loved about the thing was that I could feel the groundswell effect. I could feel that we were getting the message out there, and the engagement – I was doing quite a lot of live content, which did plenty to keep CALM front of mind for the reach that I have. I think it was it was relatively audacious, and so when I go three and a half times further, I think it’ll start to have the impact that I want the project to have.

What kind of ways will you be documenting it? How can people follow you?

I would love that people follow this on Instagram, which is a very, very convenient way of me going live in the middle of a run. I think people are quite tolerant of the relatively low fidelity. There will also be filmmaking, and we’ll be dropping conference every evening and getting some support editing everything overnight. I’m quite sure there’ll be something that looks like a documentary at the other end of this, but during it, it’ll be out through LinkedIn, and Instagram primarily, because those are just the platforms where my audiences are.

There’s a breathwork community that I’ve developed over the course of the last year and a half who were incredibly engaged and loyal. I have a few 1000 people connected via LinkedIn. In that environment, people know me as a business leader, and yet I’m prepared to talk about my mental health. I see that as the real opportunity to be honest, because I’ve been that business leader with a very long job title in interesting organisations, yet people didn’t see the full story of mental health issues and chronic depression. I think it surprises people in that forum. So I think there’ll be plenty of publishing at LinkedIn, because I think that’s where the most the most important engagement will work for me.

Can you tell us a little bit more about that period when you were at the height of your profession, but also struggling with issues in the background?

The first period was in my early 20s – I put a very, very high bar on my performance through university, probably because I was seeking validation from an absent father and wanted to be the best that I possibly could be in his eyes. I think that affected my mental health very negatively. So that was the first time I felt that I was not achieving very much in life and felt that I became a burden. In later life, I was successful, and had all of the perceived trappings of success, and a family, all of those things which externally say this person is flourishing, but internally, there was a darkness. I was functional, but I spent a lot of time in the pub. In my job as a leader in marketing organisations, it was par for the course to go down the pub and drink. And I had a very high tolerance for this sort of self-abuse to be honest. But it got to a point where I just became quite broken. Internally, I was shattering. Externally, there were very high expectations. I couldn’t really live up to that ideal that other people had of me if that makes sense. It reached that point where I was not performing as I should have done, I wasn’t looking after myself, I was letting them down. I felt that disappointment, and that becomes a vicious cycle. It’s self-fulfilling. You know, the black dog returns, and it came to the point at which I stood on Archway bridge, considering to leap of it. And fortuitously, you know, the love of my family…I didn’t want my children to grow up in the knowledge that their father had killed themselves. I had seen the consequences of that in other situations and didn’t wish that upon my children, I didn’t want them to carry that. It was less about self preservation and more about consideration for others.

So how has your journey been since then? In terms of recovery and building up to this point?

I think recovery is a constant state. It’s like being a recovering alcoholic. You will always be an alcoholic, but you choose not to drink. I am someone who has mental health problems, but I choose to manage it very, very actively. And running is a great part of that. Running is sort of oversimplified – it’s hardly that I just go running, it’s a contemplative process that I go through every morning, as part of my days. I feel balanced, I get sunlight, I get oxygenated, I look at the horizon, I connect with nature and with other people. All of that spools into whatever we understand running to be.

The journey to wellness is about my physicality and my diet. It’s about reducing the amount of alcohol, but it’s also about how anything that takes me off that path of stability becomes counter intuitive. I guess the run is just the polar opposite of being at the point at which you want to self destruct. The polar opposite of that is wanting to save a life so much that you will push yourself to the point of your maximum endurance. How much resilience can I possibly muster? Not just myself, but collectively as a team of people? How much good can there be in a run? Compared to a mental health crisis.

What’s your biggest fear in terms of the actual run itself?

Nettles. Brambles. On the Bishop Stortford to Cambridge run there were several rights of way that I don’t think anyone had used in 100 years. I can run through one or two stinging nettles, but when it’s a mile and a half long of them, and you can’t really reroute… That’s probably my greatest fear, if I have to withdraw from the run because of an injury. But I’ll cross that bridge, I won’t give up easily – it won’t be my mind, it’ll be my body. If that fails, then I’ll just start again when I’m recovered.

The fact that people can get out and get together and get behind this feels particularly brilliant after what we’ve all just been through.

And a lot of people had mental health problems because we were incarcerated and restricted from social norms. I mean, I had to move the run. It was meant to be an April, but there would have been no involvement even if I might have been able to legally do it. It was most important that people could be involved. It’s been acknowledged that one of the reasons for trying to open things up, not least for the economy, is also people’s mental well being – what I want to do is help people find the tools to maintain positive wellness.

What does the final was the final leg look like, the big finish?

October 1sr, a Friday. That’s when it comes to London. Really nice run, mostly along the canals, very flat, finishing in Regent’s Park, because it’s easy for people to park and we can just have a little party. It’s important to run into a place where people can get together and celebrate what we’ve achieved.

Learn more about Matt and the challenge, and donate to CALM, at Runthecountryultra.com

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.