The man who drove the full length of Africa – with Parkinson’s

Adventure

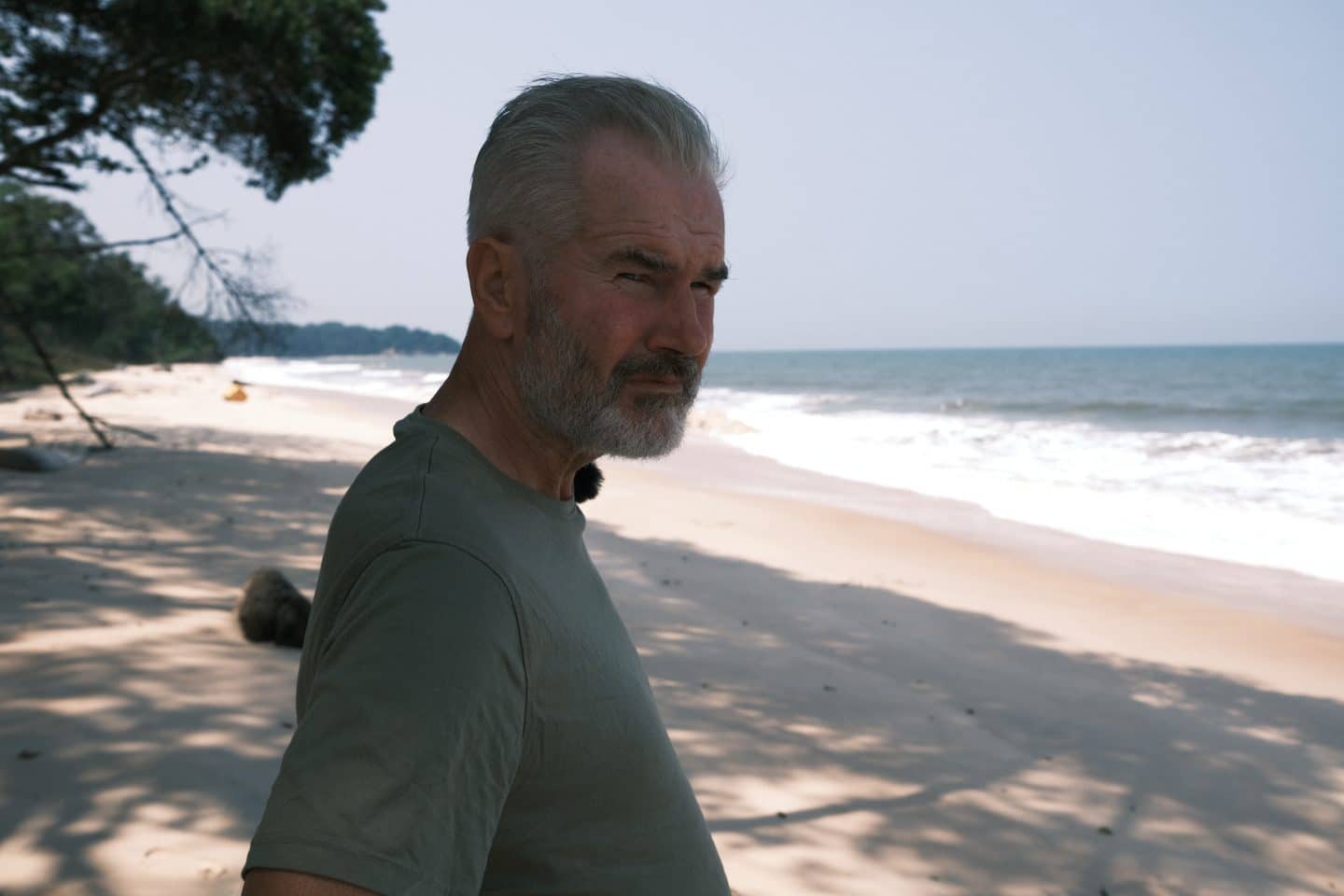

Guy Deacon CBE had a boyhood dream of driving the whole of Africa. After being diagnosed with Parkinson's, he decided it was time to do it.

Having retired after a distinguished military career at the age of 60, Guy Deacon CBE attempted his childhood dream of driving the full length of Africa. He left his home in Dorset in his VW van and set off on a journey which would take him 18,000 miles solo down the west flank of Africa to Cape Town.

An extraordinary feat to undertake, but what was even more mind-blinding was that Guy did it while suffering with Parkinson’s Disease – the fastest-growing neurodegenerative illness worldwide with no known cause or cure.

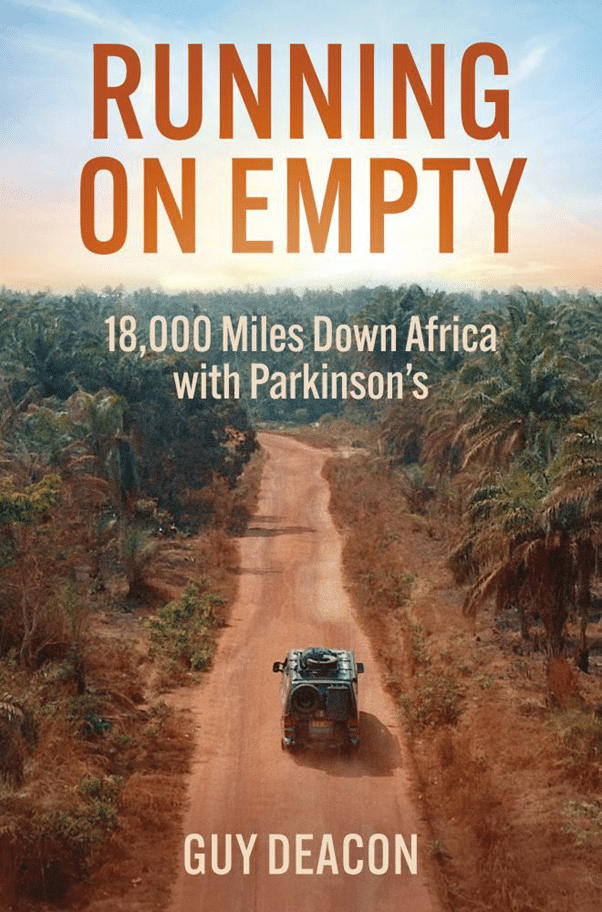

The journey is the subject of a Channel 4 documentary coming later this year and the new book Running on Empty which is out on World Parkinson’s Day – 11th April 2024.

It would take the former army officer and father of two over three years to complete – including a break due to Covid – and saw him travel across 25 countries, suffer 5 vehicle breakdowns, whilst taking 3650 prescription pills to help manage his Parkinson’s.

Guy drove, lived and slept in his VW Transporter, often in remote spots, hundreds of miles from the nearest village or town. Using patchy GPS he often got lost and relied on the kindness of strangers for help. His story is truly incredible and his work in raising money and awareness for Parkinson’s organisations both at home and in Africa, has been inspirational – as has the message he has sent to people with Parkinson’s not to give up.

We were delighted to speak to Guy to find out more about his amazing journey…

Can you tell us how and why you got started on this trip?

It started a long time ago when I was at school. I received a book through the post with a cover photograph on it, which was a picture of Land Rovers in the desert with the sun setting behind and people setting up camp.

It was so evocative. And I thought that’s what I wanted to do when I grow up.

And so I always had this idea to do that.I’ve still got the book actually.

Then when I went to university at Durham, I joined the Exploration Society and went to Kenya a couple of times, went to Algeria and started to live that sort of that dream. I joined the Army and did a couple of expeditions as a young officer into Africa and became really quite focused on traveling through Africa.

And luckily I did an 18 month tour in Congo as well.

So I was quite taken by the bug because it sort of grips you, in a funny sort of way.

I was always going to do this journey because I promised myself that I would, but it was a question of having the time and the money and the vehicle and the inclination and the motivation and everything you needed at the same sort of time.

And that came together when I retired from the army in 2019, from my job. I had a pension, and I wasn’t going to be able to get a sensible job because I had Parkinson’s. So I had time and I thought I’d get on and do it.

What was your starting point? How did you start to plan it and arrange it?

I was a bit haphazard, to be honest. For the last two years that I was in the army, I acquired the right vehicle, which was the VW Campervan, which some people think isn’t the right vehicle. But I think in many ways it is.

I did preparations. I had it the suspension improved. I had an under armour put under the bottom of it, and changed all sorts of bits and pieces to make it more suitable to live in for a period of time.

I was ready to move and to set off almost the day I left the army.

So as I moved out of the army house, I went to stay with a friend, packed up the van and headed to get the channel ferry to France.

And that was it. It was almost as simple as that.

I just packed the wagon up with all the tools. I didn’t take any spare parts – more on that in a minute.

My planning was: there are basically three ways you can go to Africa at any one time.

There’s the east route which is cape to Cairo to Cape Town, which is very well traveled and to be honest, it is the easiest route normally through friendly countries. The other route down the middle is through Algeria, into Nigeria and then down either across the top of the Congo, which is really difficult or down the western side of Congo, which is equally difficult. And that wasn’t open because Algeria is really hard to get into.

Unusually the west coast was open and it not normally isn’t because there used to be problems in Western Sahara with Polisario and the Moroccans having a bit of a battle there. Mauritania was always quite difficult and then you’d get to places like Guinea, Sierra Leone was difficult. Liberia has been difficult. So it was all quite difficult but it was open and doable.

I thought I’d go down the west coast and take my chances because I’d never been there before. It was different. People in the UK, don’t know that part of the world. It was exciting and I’d be able to clock up a few countries never really been to.

What were your other concerns going into the trip?

Because I’ve got Parkinson’s, I knew I wouldn’t be able to get a proper job when I left the army. I actually went on a resettlement course the army provided and I had a tutor and she said, ‘what do you want to do when you leave?’

And I said, well, I don’t want a job. And I told her about the trip.

She was quite surprised, but she did say if you’re gonna do this trip, then you should make it worthwhile and have a reason for it and give it some focus. She was very wise in that respect.

So I undertook to use the trip as a vehicle for demonstrating to people back in the UK that you can do what you want with Parkinson’s if you try hard enough. And I want to prove to other people with Parkinson’s that you can live your dream and complete it.

If I was going to, they could do it too. That might be playing golf, it might be going to cinema or whatever it happens to be: but you can do it, you can still live your life reasonably fully.

That was my thinking behind it.

And also I was going to film myself and write a blog and keep people following me and let people know what it was like because not many people know what Parkinson’s actually like.

They think they know, they think they recognise symptoms, but there’s a lot more to it than people realise.

And I would expose that, especially the mental issues, by completing my diaries that people could read as I was on the way down.

That was the aim of it, to show the families and friends of those people with Parkinson’s what they’re going through.

And that got me all the way to Sierra Leone, which is where I arrived just in time for COVID.

The world stopped spinning at that point and I was evacuated from Sierra Leone. I was tempted to stay there, to be honest, because at that point, Europe was far worse off than Africa. But somebody very wisely said, if you stay here and you get COVID, you’ll be in deep trouble because the hospitals are not good. Whereas if you get COVID in the UK, you’ll probably be all right.

So I came back to the UK. I though it’d be three months, you know, so I just left the wagon there.

It was two years later when I went back out to join up with my wagon.

But that time, two things had happened, which is very important.

First of all, I met Rob Haywood who by chance said, should we make a film together? And I went, what a good idea.

And I met Amado Thomas from Parkinson’s Africa who explained to me some of the details of the Parkinson’s issues in Africa. And that allowed me to focus my attention even more closely on what I was doing.

I wanted to raise awareness of Parkinson’s in Africa for Africans and for Europeans as well, so they could see what was going on because it’s a very different story in Africa.

That gave me a sense of purpose if you like rather than just drifting down through Africa. It meant I went to capitals, I saw people, I arranged to meet people.

I got on television programs, newspapers, radios and started a conversation in all the countries I can get to. And that was my aim to raise awareness, right?

What can you tell us about the situation over there with Parkinson’s?

Well, there are 50 countries in Africa as you’ll know. Each is a bit different and each has a different way of treating medical issues.

For instance in Uganda, it’s quite a progressive country yet it’s take on Parkinson’s is as bad as it gets. Because there’s no known cause and there’s no known cure and it manifests itself in a rather unpleasant way – lots of trembling and irrational body movements – people are very frightened of it and it’s assumed to be the result of witchcraft. And people have been cursed if they’ve got it.

What happens is, people are abandoned. They’re left to their own devices and their family leave them willingly. The person with it says ‘you must go’, because they think it’s contagious and they don’t want their family to get it.

They go ‘leave me, leave me’ and they end up being left alone in isolation for as long as it takes them for to eventually die. And that can be a long time. Parkinson’s itself doesn’t kill you, but it makes you very weak and makes you susceptible to other problems.

In a country like Uganda which could know better, that was exactly this is happening. And because people don’t record it and don’t have anybody looking at it particularly closely, they don’t know how big the problem is. Therefore, they don’t try and do much about it.

It’s just one of many problems because they’ve got all sorts of other things like malaria, Ebola, everything else as well. Parkinson’s is just another problem.

What particular difficulties did you face day-to-day?

The roads and the mechanics of the trip were quite complicated because the roads are not good. In Africa, the worst bit is not the mud tracks, because you just go slowly and you grind your way through them. It’s the tarmac roads and the potholes. The potholes play real havoc on the suspension and it’s very uncomfortable and it does real damage. Potholes and speed bumps which are like walls built across roads that you don’t see until the last moment.

The practical aspect caused me some problems, but of course I had Parkinson’s so I was taking a lot of tablets as I was going along. And when they weren’t being affective, because they wear off very quickly, I’d have to stop and spend a lot of time just resting and waiting to get better.

So this was all a patience game as well for you?

Yes. Well, I had time. The one thing I had was plenty of time and in my experience, if you don’t have time, you end up rushing and if you rush, you’d make mistakes and make the wrong decisions and that causes all sorts of other problems.

But I had time so I could take it peacefully and just gradually do it bit by bit. And I had a list of contacts, most of whom I’d never met, who I could plug into and go and stay with and visit on the way down whilst I needed a visa sorted out or the car mended or whatever it would be.

Can you tell us about some of the highlights?

The highlights were the people I met along the way and the countryside I went through. The great thing about traveling rather than being in a destination in Africa is things change as you’re moving down south. You go from mountains to desert, to savannah, into jungle.

And this unfolds in front of you as you’re traveling along. Everything changes, the vegetation changes, the climate changes, the mood changes, the music changes, the food changes, the shape of people, changes, the language changes. It’s wonderful, actually wonderful.

Did you get a lot of help along the way?

There were always people willing to help and the message that comes out from the book is when I had a problem, there was always somebody there who could help me put it right.

Always. In Gabon, I hit a huge pothole and bent the suspension. The shock absorber bent in half and the wheel was at a funny angle and I couldn’t go on. It it was all a bit difficult. But the first car that came past said, ‘are you all right?’

And I said, ‘Well, actually not really.’

‘Do you want help?’

And I said, ‘Yes, please if you can.’

And that chap and the next chap who drove past in a big 18 wheeler lorry stayed with me from four o’clock in the afternoon till midnight to get the vehicle in a mobile state and to get me down to the next village where there was a mechanic. Then they were there for the drive down the road and they stayed with me all night long to make sure I was right.

And the next day they came and said, ‘is everything ok?’And they wouldn’t leave the village where they deposited me until they were sure I was all right.

I then left the vehicle there and went down to Libreville where I was going to meet the film chap, Rob Haywood. And I went by taxi and the taxi took another person in the taxi as well. I never met him before and he was going to for his own business. We were stopped by the police at a checkpoint and the taxi driver was apprehended because his vehicle paperwork wasn’t right.

We were stuck by the side of the road. And the police said, ‘well, there’s nowhere to stay.’

So I said, ‘well, can we stay in the police station?’

We spent the night in the police station sleeping on the floor. And the next day, the police dropped us off on the road to hitch down to Libreville. And the fellow who came in the taxi with me wouldn’t leave me until he was sure I was deposited in the hotel. He came with me all the way and said, ‘right I think, you know where you need to be, have a safe rest of your journey.’

And I have no idea what his name was. It was just amazing and that kind of thing was pretty common really.

How long was the second time out there?

The first was about four months and then it about eight months. The second half was a lot longer and the time was taken up waiting for visas, waiting for the vehicle to be mended on occasion, all that sort of stuff. Also there are no VW spare parts anywhere between Morocco and South Africa.

In fact, there are no VW parts anywhere.

They’re so confident their vehicles are gonna work, they don’t seem to have any spare parts. But I needed them and I couldn’t get out there. I had them shipped out from the UK by a chap called Rob Willis who ran Volks Trek, who’d helped me set the vehicle up in the first place. He would literally collect the bits together, go and drive to whoever was flying out anywhere near me, give them a package to take in their hand baggage and people would fly out with a clutch, spare brake pads, spare bits and pieces.

That happened on a number on about four or five occasions. Nobody came to visit without bringing it spare parts.

Incredible. What was it like when you came to the end of the journey?

It’s funny actually, we talked about a grand of arrival in Cape Town with the ambassador and this, that and the other, but of course, Cape Town isn’t the only capital in South Africa. And there was no obvious place to go to. No Eiffel Tower or Marble Arch or anything like that. It was just, just another city.

I was deflated and elated. I’d done it, a job was done, but what was I going to do next?

It was the end of 30 years’ worth of dreaming, three years worth of concentrating on and one year’s worth of traveling and it was stopped and I had nothing to look forward to. I’m coming back to England with Parkinson’s Disease and I thought ‘this is not good’.

It was a miserable experience to be honest.

How did you sort of pick yourself up from that point?

I didn’t fly back from straight away. I went and sort of recuperated in South Cape Town. Found a place at a campsite where I could literally do nothing for a couple of days. Just lie down and drink the odd beer but just chill out and just relax.

There was a friend who I knew of old who was there. So I stayed with him for a bit as well and just recovered my strength really. And then organised the truck to be shipped back to the UK, which it was very easily actually.

And by then I was back under normal control and I flew back shortly afterwards to be met by the prospect of writing the book and doing the film.

So what do you hope that people will get from the book and the film when it comes out?

The first thing is I want them to understand in the UK is that when it comes to Parkinson’s, it’s not as simple as people think. There’s a lot of mental processes going on as well and people with Parkinson’s have all sorts of reasons to be depressed – not least of all, they haven’t got any dopamine which makes them happy. So they start off from a negative position anyway.

And then they’ve got all the frustrations and complications having Parkinson’s to live with as well and they’re probably not telling their friends and their family about it.

They’re probably buttoning it up, which is what I do or did. And they need to talk about themselves. Or I can say it on their behalf. And that’s kind of what I’m doing.

Secondly, those who’ve got it, I want them to know they can’t give in, they’ve got to get off their ass and they gotta do things and if they try hard enough they can.

Also I want people in Africa to know that there are people in Africa who don’t understand Parkinson’s and need to – because if they do understand it and they recognise it for what it is, a straightforward neurological condition, then they won’t treat each other with such extraordinary sort of disdain and just mistrust and they won’t abandon people. Because in my view and my personal experience, the pills are really good and they work really well.

Neurologists can’t do that much cos they can’t, there’s no cure. All they can do is do prescribe pills.

But what makes the biggest difference is being cared for properly and being loved and cherished by your family, who don’t abandon you and do things for you and help you. And that’s not happening in many parts of Africa. They’re being left to get on with it.

And that for me is, is the thing we want to try and fix because that costs nothing and makes the difference to everything.

What did you learn about yourself throughout this trip?

I was in denial of Parkinson’s.

I sort of put it into a box and ignored it and carried on working. And with reasonable level of success. I thought I could do all the things I usually do, it’d just take a bit more time.

But the reality is I can’t do the things I used to do anymore. Or if I am doing it, it would take a very long time, so as to be impractical.

So I recognised I’ve got to come to terms with having Parkinson’s and realise that I can’t just ignore it anymore. That’s the first thing.

Second thing: I’ve got a story to tell and I’ve got to tell it.

I can’t not tell it. And I want to tell every everything about it, including the difficult bits. There are times when the choices are get off your ass and do something or just lie down and drop down dead.

Are there any other challenges for you now? Anything else planned?

I’m quite occupied with putting this one to bed. I’m doing a lecture tour which will include some locations in the United States.

But if there’s enough interest in what I’ve done, I intend to go back and do the other half and come back up the east way. And rather than going through Sudan and Southern Egypt, which is a bit tricky, what I’d like to do is go up through Ethiopia and then across to the Red Sea to Saudi Arabia and up there.

So that’s what I’m thinking about doing.

Running on Empty by Guy Deacon is published on World Parkinson’s Day. All proceeds from the book go to Parkinson’s charities. Find out more about the book here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.