Icarus Rebooted: The Man Who Achieved Human Flight

Technology

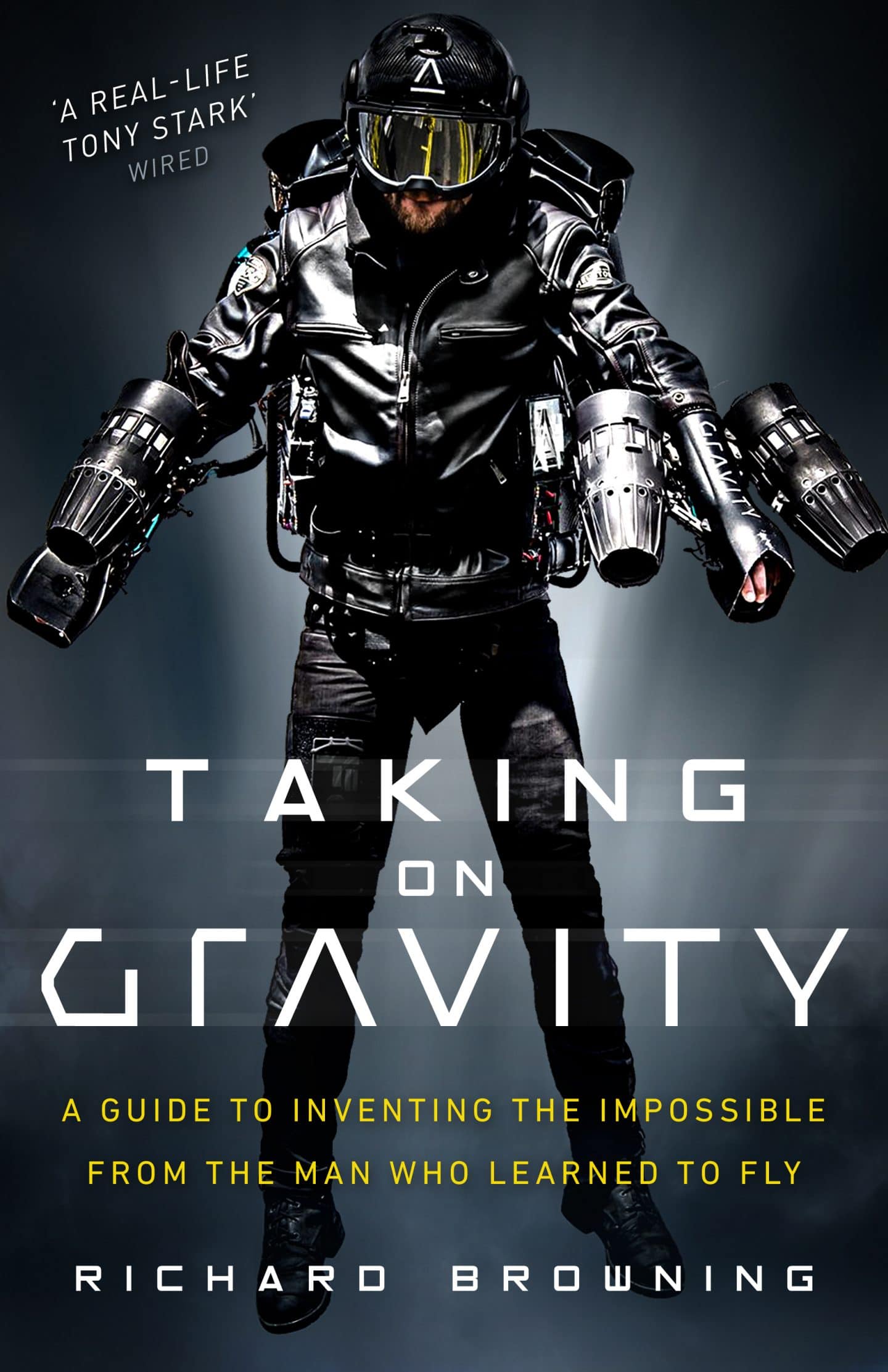

Richard Browning is already an icon for his real-life "Iron Man" escapades. But as his new book shows, it's the personal story of dealing with his father's death - and learning from his inventive life - which is the truly inspirational thing about this remarkable new British hero.

Richard Browning is the founder of Gravity Industries Ltd, which already sounds like some secret superhero Wayne Enterprises-style cover company – and actually is. Apart from the secret part. Yes because Richard is very visibly one of the most exciting inventors/entrepreneurs/daredevils on the planet thanks to his innovations in the field of human propulsion technology: basically, the dude flies. Famously he developed his own jet engine powered flight suit and too his first short flights with it on a farm in Wiltshire, called the Daedalus suit. Daedalus was the father of Icarus in the Greek myth, and though Richard’s approach to human flight is far more safety conscious, there is a pivotal father-son relationship running through this story, that of the suicide of his father, who himself was a maverick inventor. It has led Richard to carefully manage his business, and himself, as well as test the limits of what humans can do, and in the process he’s become a deeply inspirational human, as compellingly shown in his new book, ‘Taking on Gravity: A Guide to Inventing the Impossible From the Man Who Learned to Fly’…

How did you get started with this journey of achieving human flight?

I like challenges – I spent 16 years as an oil trader with BP, spent time in the Royal Marines reserves, and I got into ultra marathon running, lots of things in my life that have illustrated a desire to take on a challenge. When it came to human flight my whole family history was caught up in this: my grandfather was a wartime pilot, and the other grandfather used to run Westland helicopters back in the 70/80s. My late father was an aeronautical engineer and maverick inventive designer. He unfortunately took his own life when I was 15, because of a failed entrepreneurial innovation journey. So it’s weird, I had a split personality of having that in the blood but also having a very brutal lesson at an early age of what can do wrong when interesting, crazy ideas don’t manifest, and how you can make that journey survivable in every sense.

It took me putting away enough money over 16 years with BP to finally, gradually, open the taps on the inner father, and the idea of applying what I learnt in the marines about the mind and body to human flight: by adding just the missing amount of horsepower but using the brain for balance, stability and control. And doing it all for the joy of the challenge, there was no commercial rationale whatsoever, it was just: wouldn’t that be cool if it worked.

It was not at all inspired by the Iron Man film, but clearly it’s funny how science fiction does inform on later evolution even when it comes to the phone I’m speak to you on now, which was hypothesised by Star Trek a while back.

I the original TED talk I did, you see that just by cobbling different ideas of how you’d augment with human form with that horsepower, I fumbled my way in my free time evenings and weekends, towards managing to get off the ground and fly around. I realised it had such a big impact on people when they came to see it, even my mother in law had tears in her eyes and gave me a hug after she saw me flying around in this little Wiltshire farmyard: I thought I should try and formally share this with people. I launched the company in 2017, and I’m now sitting here with 103 events in 30 separate countries, 5 TED talks a team of 7 other pilots, a race series, military collaborations, and we also train people how to fly within a couple of days. It’s been a ludicrous journey, which you can trace back to having a crazy idea for which you safely fail towards succeeding in a way you never imagined.

Can you tell us about the early stages and dealing with the physics involved?

It was that process of if you can train the human mind and body to ski and rollerblade, if you can train your balance system to adapt to that, then why can’t you adapt it to balance a form of propulsion. Then you look at different forms of propulsion and find that the most energy dense out there is the gas turbine – well, strictly speaking it’s a nuclear reactor, when it comes to horsepower per kilo, but that’s clearly not an ideal option! – then explored model aircraft engines, and those used for target drones, these micro gas turbines. I got hold of one of those, and knew enough about them to try one. The big step was strapping one to an arm which was very much not advised in the guidebook. And then gingerly playing with the power and realising actually very quickly that a lot of the assumptions that would make most engineers not even try this were not valid. Even though it’s pushing with a lot of force, that force can be simulated on a table: if you lean hard enough on a table with your 80, 90 kilo body, that’s a 45-odd kilo force. If you substitute that for the force of a jet engine, it feels exactly the same. There is no torque, no inertia, no rotational gyroscopic fighting force because the spindle mass was so small and it accelerated relatively cautiously up to 100,000 rpm. It was very manageable. You could stand there in a country lane in Wiltshire realising you could achieve stage one of substituting a momentary impulse of a table with that gas turbine.

Then it becomes a question of where you do put more of them because you need a certain amount to achieve the required force. Putting them on the arms was fairly easy but you can’t put them all on your arms because it becomes a big challenge then, so I put them on the back of each leg which worked in theory. but it wasn’t very comfortable and it had challenges. like destroying any ground surfaces you’re stood on because the engines were just so close to the ground. And the fact that you’re a bit like a puppet, you have to balance four limbs that are all being pushed against. I managed it but later on we moved the engines up to the back.

What was that first successful flight like?

On the video for the very first 6 second flight, you see me in a grainy image spin round and grin when I managed to land, because that was the perfectly defined moment when it went from a crazy idea to something that demonstrably worked: flying a human being across a farmyard for 6 seconds. I distinctly remember the thought process, which was deep concentration and trying to maintain this really hard ‘rubbing your stomach patting your head’ thing in terms of four limbs. You can see me fighting one leg which was twitching as I tried desperately not to bend it because as soon as you bend you leg, it all goes wrong. But at the same time realising, ‘Oh my god this is working,’ and trying to cling to the balance and control and not end it too quickly that I couldn’t claim a victory, but also not let it go on too long because I’m in uncharted territory, I’m live learning how to do this as its going. Upon landing it was a significant amount of relief that it had worked and I’d made it without falling over. So really it was all rolled into that one six second flight.

How important was it to do it all yourself?

Oh the testing, absolutely. I can’t think of anything worse than building something mad then standing back and let someone else get in it. And then go and hurt themselves. No, it is on every level preferable to have you as the guinea pig and I’m not being a hero about it, it’d just be horrible to have a 20 something intern break their leg because of the thing you’ve just built.

From a practical point of view its vastly more useful to get the feedback yourself. Then I exactly know what’s working and what isn’t. And then there’s a practical thing as well. I did have some help from the electronics point of view but unless you’ve got a big bucket of cash to throw at this, you are in a mode where a lot of what you’re trying to develop either doesn’t exist or is going to cost a lot of money to custom commission. So a key enabler to this journey was realising that actually nearly everything required to get out and test was within my reach. You can rip the gun trigger out of an electric drill and then realise that could make a perfectly good throttle for the arm, hey presto, you’re off! You’re not custom commissioning a $100,000 special trigger. Part of the journey was about repurposing existing things, to get out there and test and learn. That was another reason not to have an army of people around me.

What kind of training do you have to do to get your body prepped for this?

I wasn’t sporty at school but I got into running and then the Royal Marines training was quite brutal. I emerged from that with a real interest in triathlons and then I dropped the cycling and swimming and got into ultra marathon running.

From there I got into rock climbing and calisthenics: that whole discipline of doing muscle ups and flags turned out to be perfect because it’s all about strength-to-weight ratio. It’s not banging out massive squats its about using your own bodyweight and staying as light and as strong as you can. Which is really handy if you’re flying, you want to be as light and as strong as you can be to cope with the weird stresses exerted on your body while you’re learning how to make it work. In the early days it was very strenuous now we’ve made it very easy.

What were the reactions like when you first started doing public shows?

I cannot show you any film clip to prepare you what it’s like when you do see it live. It’s a bit like formula one racing – as those cars go past and that visceral smell and shockwave and terrifying sound percolates your entire soul, that kind of visceral experience does not come across on a film clip. When you have that cocktail plus the visual of a human literally hanging in midair in front of you – and because all the gear is quite profiled, you can’t see it – your brain can’t consume it, you find people react like they don’t know where to place the visual memory of that in a pigeonhole in their minds. ‘I can’t process it.’ I’ve had people in tears and experiencing a profound impact because that dream of human flight, which has resided in the world of Marvel CGI, or legend and make believe, now we, frankly through a large chunk of luck, have snuck the right side of this magic line that says that’s a human being flying. ‘They’re not hanging off or sitting in a flight vehicle, that’s a human flying and I can’t process it.’

That’s why we’ve had so many events, and is also why we’ve scaled it up to a race series as a way of building on the momentum around the world. Scaling it into several pilots all flying round a Red Bull style pylon course, over water so its safe and yet it looks dramatic, this Iron Man/Red Bull visceral entertainment spectacle.

Have you refined the suit from experiences doing the events?

Oh most definitely and we’ve had 5o or 60 clients who have come training with us – most of them are still on the training tether but flying pretty well by day two. The very fact we’ve had 70 year olds and girls and all manner of different people come and learn that quickly is a demonstration of how good we’ve made it now. Its hugely refined and also there’s so much more manoeuvrability and speed and control now.

Where do you see this going, what’s your inclination towards?

We’re committed to pushing the technology ever further to see where it can get to. Some people ask about mainstream transport – it’s absolutely not ready for that yet. But it’s like how the first motor cars were noisy and inefficient and everyone thought they were a joke compared to a horse – especially with the electric version we’ve built, if you can get a better energy density solution, in other words better batteries, then who knows?

You could ask what the point is, which is the valid question, you then ask what is the point of a Formula One car, or a NASCAR, they don’t do anything practical but they do entertain. They inspire, and they leave behind interesting technology. So it suddenly dawned on us in a very cheap way – because really we can make this vastly cheaper than even a fraction of a formula one team – why don’t we do that? That human competitive element generating entertaining spectacle and content.

Parallel to that there is a niche search and rescue and special forces mobility angle which is fun.

The special forces guys must be all over this…

Yeah because of my Royal Marines background it’s a huge bonus to be welcomed by them, even though it’s a long time since I worse my beret in anger 12 years ago. We’ve been able to do the exercises you’ve seen on Instagram. Landing on a moving naval vessel, things like that. To be honest even if we don’t get to see decent money out of the military, it is massive fun hanging out and doing stuff with them. And well, it doesn’t do our image much harm to tease that angle – the public are always wondering about the murky special forces stuff we’re doing, and actually that’s authentic! We have a bunch of interesting stuff going on.

On the mental health side of things, how do you look after yourself and the way you handle your business?

Being an entrepreneur, an innovator or a designer, or anybody who takes on the kind of challenge that isn’t already a low risk done deal, has to generate their own processes for coping with success and failure. The more outrageous the challenge, the more failure you’re going to have to wade through. There isn’t any magic formula for that; you’re a fool if you’re taking failure constantly and don’t ever see any success, but at the same time you have to take a lot of failures to see that kind of success as well. So a big part of our ethos, is about simply making failure survivable. You know from what I said before about my father why I feel deeply about that.

If we go and build a prototype and test it and it’s a bitter disappointment and I’ve wasted the last 3 days of work on it, I’ve just got to know I can survive that failure. Clearly safety wise there’s the concern of is this going to catapult me to 300 foot in the air and then fail? That’s not acceptable I won’t get to have another go if that’s the outcome of failure, but there’s also financial concerns: have I thrown so much money at our races that if they failed would we be bankrupt and can’t carry on? If the answer’s no to any of those, we don’t do it. We run everything we do on that basis – can we recover from failure? And I think that’s the way I keep myself sane on the journey.

It’s understanding you have to take risks but then making those risks survivable. That’s it.

Trending

Join The Book of Man

Sign up to our daily newsletters to join the frontline of the revolution in masculinity.